Jordan Peele made his directorial debut to critical acclaim in 2017 with the American horror film “Get Out.” The socio-political concerns of that film felt timely and prescient in a way that few contemporary films have. Peele’s follow-up, “Us,” another American horror film, feels weighted and buoyed by the response to the first. “Us” has followed up the critical acclamation of “Get Out” and with only two films under Peele’s belt, contextualising this film in relation to that film feels almost unavoidable. Little in it suggests an explicit relationship to its predecessor. And yet, the way “Us” feels tethered to what came before feels apt to some degree. It feels indicative of the way that “Us” both invites and rejects interpretation and meaning.

Jordan Peele made his directorial debut to critical acclaim in 2017 with the American horror film “Get Out.” The socio-political concerns of that film felt timely and prescient in a way that few contemporary films have. Peele’s follow-up, “Us,” another American horror film, feels weighted and buoyed by the response to the first. “Us” has followed up the critical acclamation of “Get Out” and with only two films under Peele’s belt, contextualising this film in relation to that film feels almost unavoidable. Little in it suggests an explicit relationship to its predecessor. And yet, the way “Us” feels tethered to what came before feels apt to some degree. It feels indicative of the way that “Us” both invites and rejects interpretation and meaning.

The film begins in 1986, when a young girl, Adelaide, is briefly lost in a funhouse on a beach where she encounters what seems to a doppelgänger. The event leaves her traumatised for a time. As an adult, Adelaide and her family are on vacation near the beach. Adelaide, who seems to still be suffering effects of the childhood trauma, is increasingly circumspect about venturing near the beach. Her fear is later proved justified when a Shadow family, made up of doubles of her, her husband and their two children, appear in their vacation home’s driveway. The home invasion by these Shadow-selves sets off a high-octane horror chase and then an existential thriller as people around the area are haunted and then hunted by these Shadow figures.

The title “Us” is such an effective distillation of the things the film is working on. Of all the personal pronouns (I, mine, her), there’s something about the word “us” that immediately suggests the existence of a binary opposite. For if there is an us, then there must be a them, and if those two binaries exist then between must be some division. Implicit or explicit. That division is significant. Peele utilises our expectations and our desires to fill in the blanks to create the labyrinth of the film.

“Us” commits to its thematic focus on duality. Even before we are introduced to the Shadow family, the film is explicit and thoughtful with its visual language, especially with its use of mirrors, windows, and surfaces. If “Get Out” seemed bound to its screenplay, a deliberate satire best expressed through its build-up of plot, “Us” feels more deliberately attached to its technicalities. There is the blood-red costumes of the Shadows and the pulsating score, which manages to conjure feelings of calm and unease at once. “Us” is at least consistently stimulating. But the question of what it stimulates and why it might be doing so are more difficult to parse, and it’s a riddle I’ve been trying to make sense of since I’ve seen it.

With a hoarse, punctuated by gasps, Adelaide’s Shadow sits the family down in their living room and begins to tell a story, a dark fairy-tale, her story. Adelaide, her husband, her daughter and her son are dressed for bed. Their Shadow selves stand opposite them, poised for battle. They are divided, even if the line is invisible. On one hand the affluent, privileged family, comfortable and at peace in their lives in the sun. On the other side is the Shadow family, tethered to their original selves but messier and unhappier. Without privilege, without agency and in the darkness. “Us” is teasing us with the context of these doubles. It’s a teasing with many fall-outs, though, for our thoughts immediately go awry. If these are shadows then that means they are the same as their human counterparts. Except, shadows exists outside of us even as they are technically us.

I immediately recoil against reading too much into “Us” too soon, because an intellectualising of the experience seems immediately false for engaging with art which needs understanding through the senses. And yet, everything in “Us” feels devoted to explaining or contextualising itself even as it insists on a striking but then exhausting opacity. From her first appearance, Adelaide’s double, the only one that makes intelligible sounds, seems committed to explaining herself, and so we are left to work out that explanation with her. Explaining and contextualising is part of the film’s own text. Part of the appeal of the film is that slippery unwillingness to define itself as just one thing, but the more I think of it the less that ambiguity seems like an explicit mark of a film in control of its narrative.

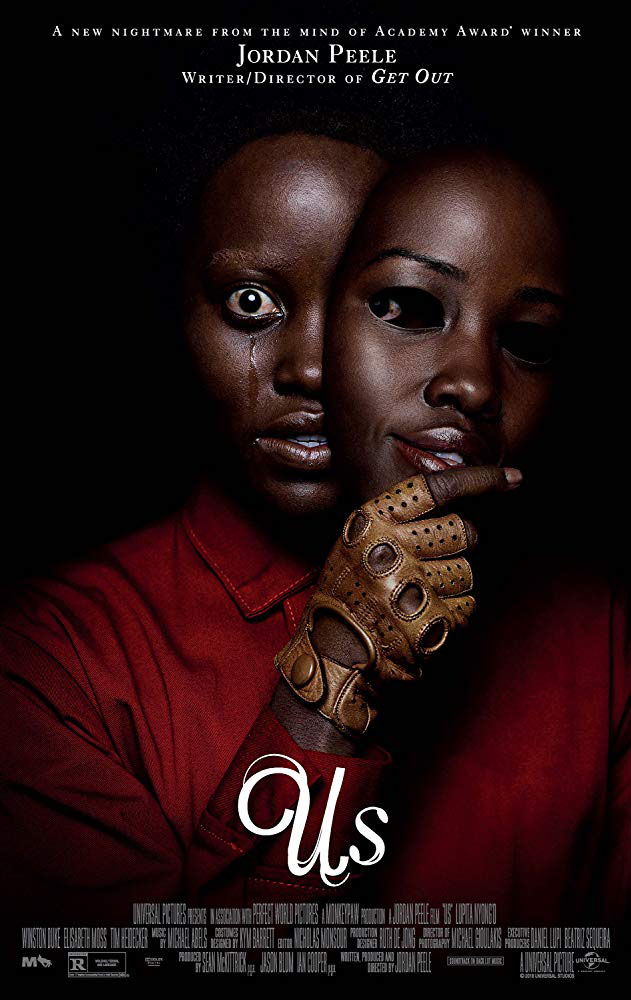

Lupita Nyong’o is excellent as the stressed Adelaide and as her malevolent double. Peele’s strength with actors is emphasised here, including a particular talent for drawing accomplished turns from his child-actors. Elizabeth Moss, in a brief role, is the second best in the cast, with a wordless scene in the middle of the film that’s haunting in it perversity. Everything in “Us” is committed except its own story. It is an allegory, certainly, because it cannot work if it’s not an allegory and that is where the film falters. Figurative devices are mired in their duality. They are about that tension between the perceived and the actual. Between appearance and reality. Puns. Metaphors. Irony. They all depend on a discrepancy between two things but, for a figurative device to work explicitly well the effectiveness must be effective on both levels. It must work on the literal level, and then gains added value from its contextual figurative level. “Us,” though, feels like a ball of thread that always unspooling. It’s consistently moving but it does not seem to be going anywhere and it does not seem to have any context. And that’s where it feels too schematic and discursive to sustain itself.

There is much that can be read into it, and in some cases, “Us” is similarly focussed on pointing to, or implying multiple possibilities but it plays fast and loose with them by never managing or allowing itself to decide which. Its ambiguity is not its issue, but “Us” seems to want us to solve it. But the slipperiness of its ambiguity and its unwillingness to resolve itself is fascinating even when it is frustrating, confounding and ultimately unsatisfying. I don’t care much for “Us” and the more I think of it the more empty it feels. It is an intriguing exercise to watch, but one that leaves you more perplexed than energised. It is compelling for its sheer provocativeness. It nags at you. That’s to its credit. I’ve been thinking of it since I’ve seen it. But being provoked does not mean one is enamoured and being curious does not mean that one is committed. The many possibilities of meaning in “Us” mean that it could be about everything. But by its noncommittal response to all it invokes, it feels like it’s not about anything.

“Us” is currently playing at local theatres.