(Trinidad Guardian) Looking at 25-year-old Collin Gibbs, at first glance, one sees a smartly dressed and peaceful looking young man. He’s soft-spoken but so articulate. No one would believe that just 13 years ago, the Ministry of Works and Transport employee was completely illiterate and also a victim of child neglect. In his interview with the Sunday Guardian, he chronicles the events of his childhood, which mostly evokes overwhelming emotions of sadness but also undeniably speaks of his stark resilience.

Gibbs grew up with his mother, Coreen Gibbs, an alcoholic and his stepfather, Timothy Pierre, a convicted murderer. His biological father abandoned him from birth.

A young Gibbs spent his days home with his brother while his sisters were sent to school. It was the belief of Pierre, a semi-literate, that the boys should not be educated. There was no opposition from their mother as Pierre was the sole breadwinner.

![]() Gibbs also described his stepfather as a very controlling and belligerent man. They were never allowed to play outdoors with other children, nor could anyone—family or friend, visit the home. He was also occasionally abusive, both verbally and physically. And often times, they would be sent to bed very early in the evening.

Gibbs also described his stepfather as a very controlling and belligerent man. They were never allowed to play outdoors with other children, nor could anyone—family or friend, visit the home. He was also occasionally abusive, both verbally and physically. And often times, they would be sent to bed very early in the evening.

Waking early one morning in 2005, Gibbs knew right away something was wrong when he saw his older sister, Stacy, missing from the spot in which she usually slept. At first thought, he believed she might have run away again having done it before, when she took him with her and escaped to Pinto, about a kilometre away from Demerara Road in Arima, where they lived.

He was further convinced she ran away when his stepfather sent him and his older brother Ryan in search of her.

“While we were looking for her, Ryan said, ‘Collin, Pierre killed Stacy.’” I could not believe it and I doubted him, even calling him crazy because it just did not make sense. It was years that we were living with him.”

Ryan subsequently communicated the same message to their mother who also could not believe that her common-law husband of so many years would commit such a crime, let alone against one of his stepchildren. But with Stacy missing and no inclination to her whereabouts, she finally confronted her husband, asking him if he killed their Stacy. He vehemently denied it until Ryan told an aunt who alerted the police. Pierre was interrogated and eventually confessed to the killing. Based on his confession an excavation was carried out to retrieve the body, which was dumped mere meters away from their home.

Through a considerably generous crack in the wooden dilapidated structure in which they lived, Gibbs said his brother witnessed Pierre rape, strangle and chop Stacy, before wrapping her body in plastic and dumping it in a cesspit, across the street from their home, also dumping a bag of cement on top her lifeless body, perhaps in the hope of disguising it. In 2016, after 11 years, Pierre was finally convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment.

The murder of her firstborn, dealing with grief and denial, made Gibbs’s mother become increasingly dependent on alcohol, even regularly drinking the pharmaceutical bay rum.

At this juncture, the lives of the four remaining children got even more tumultuous. They would be consistently moving from house to house—staying at family, neighbours and at times, even complete strangers.

Gibbs would assume the role of “father” to his sisters, looking after them and ensuring they attended school with whatever little assistance they could get from those who took ‘pity’ upon them. Coreen—a short stature mixed-race woman—was too ‘strung out’ on alcohol to execute her role and function as a parent.

He talked about days on end eating “sweet rice”—rice and sugar. When that was not available, the only thing close to his mouth would be the saliva in it.

They would soon settle in an abandoned filthy makeshift formation with their mother’s new boyfriend—“a mad man shoemaker” as Gibbs described him.

But it would be at this dwelling that Gibbs would be “rescued”. Lucky for him and his siblings, a social worker who lived in the neighbourhood, noticed they were not attending school and intervened. Gibbs, 12, would soon find himself attending the Sangre Grande Government Primary School in the infants’ department, now learning the vowel sounds and how to write.

“It was very embarrassing for me, because other children would come and peep at me and laugh at times,” Gibbs recalls.

As humiliating as it was, even then, he knew he had to try. By Standard Two, now almost 14-years-old, on the argument he was getting too old to go through all the standards, Gibbs was skipped to Standard Four and was signed up to sit the SEA exam. This brought panic and confusion to his then young mind, reasonably so, moving only recently from being totally illiterate.

“I was really concerned because I already didn’t know everything and now I am about to sit a qualifying exam with chunks of work I would have never done.”

But perhaps God sent help in the form of his Standard Four teacher, Mrs Ali, as he recalls her name. She would take Gibbs under her wing and successfully prepare him for the exam.

“She worked with me every day, staying back after school. She used to tell the class she was only coming to school for me because I really want to learn,” he says through a half-smile.

With Ali’s encouragement and belief in Gibbs, he sat the exam with confidence and would blow himself away with the results. Scoring 91 out of a 100 in Math and 64 out of a 100 in English—Gibbs passed for his first choice, North Eastern College.

Overjoyed at his victory, Gibbs said many came ‘bearing gifts’ of schoolbooks, uniforms and all that was needed for him to attend the school. Ali, he remembers, gave him the biggest hug, following on with the words, “I always knew you could do it. I am so proud of you!”

He continued to excel at secondary school, becoming one of the more noted academic students. But he also threw himself into some vocational studies and sport, both of which he effortlessly outmatched.

Toward the end, he acquired eight O’Level passes, six of which were grade ones. He also received several awards for his overall academic performance throughout the years spent at North Eastern College. This, he tells us, was achieved through late-night studies with the use of the street light, as there was no electricity at home.

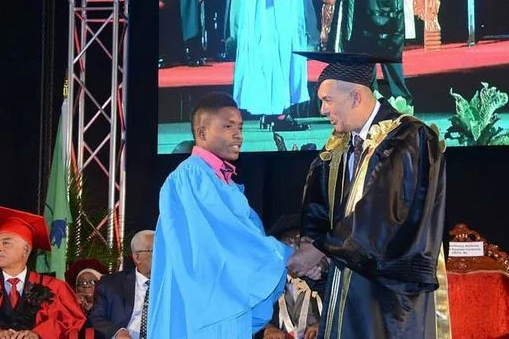

It must have been one month since his mother passed before he went on to attain a diploma in civil engineering from the University of T&T (UTT). This was a difficult pill for Gibbs to swallow, since he felt as though his mother had fallen prey to her “demons”, and she was really all he had.

“If she were here, she would cry,” he says in a mellow tone.

That aside, Gibbs is also a budding songwriter and singer who has penned and recorded several songs which could be found on his YouTube channel under his sobriquet, Colly Boss. He is also the coach of the Sangre Grande Supreme Squad Rugby Club.

From poverty and illiteracy to academic awards and the turning of tassels, confirming his new-found graduate status. Today, this simple but beautiful tradition is performed at commencements across the country. Gibbs embodies victory and perseverance.

Asked to share some words of inspiration, he says, “You could never know who or what you can become if you are satisfied with whom you are. Never judge yourself based on the present reality or the unavailability of resources. Allow what you have to be acceptable to make you more than qualified to be a success.”