Now that Bartica is a town, Agatash, a small scenic community 3 miles away, could perhaps be deemed a suburb. It is obliquely opposite the famed Sloth Island and a haven to its population of 450 residents, who are among the friendliest people I have met.

One uses Second Avenue, Bartica to get to Agatash, by means of a taxi, which must climb several steep hills. Once across the Quetaro Bridge, you are in Agatash. The name is said to be of Arawak origin: ‘Aga’ meaning water and ‘tash’, land.

Organised religion abounds. Villagers are members of the Full Gospel, Presbyterian, Seventh-day Adventist and Anglican churches. I visited on the Phagwah holiday and children filled the road running to rub powder on each other.

Regional Vice-Chairman of Region 7 Olinda Griffith was born in Bartica. Most of her childhood was spent at Blake, Parika and Le Ressouvenir. She later returned to teach at Blake’s Scot’s School. Griffith also taught at a number of other schools in regions 3, 4, 7, 9 and 10; Agatash Primary was one of these schools and during that time, she lived in the community.

Griffith’s job has taken her into various parts of the interior including Chinoewing, a place she has a soft spot for as it relates to the surrounding mountains and clear running creeks. However, she chose to remain in Agatash.

“When I came here, we hadn’t a proper road. I had to learn to operate an outboard to get from here to Bartica. I like it here because of the fresh air and that one hasn’t to worry about vandalism and it has a lot of land space,” she said, adding that her plot of land amounts to a total of ten acres.

“The village has been around since the early 1900s,” she added. “Some of the families I knew about during my time were the Murrays, Corrays and Suttons. These were crown lands that were given by the queen during the colonial times. Most of the front parts were grants given to the earlier people.”

In the early years her family did farming and livestock rearing. Many of the older men then were boat captains who worked for mining companies. Today many of the younger men have taken up with mining as well. Some of the community’s women are employed at the Agatash Health Centre and as teachers at the school.

The youths of Agatash who would have taken up mining, Griffith further said, would have been forced to do so because their academic levels are low. Nothing has been done to fix this, but Griffith is certain that a vocational school will give young men the option of learning a different skill and staying and working within the community.

Most villagers depend on the rain for the water or from the few standpipes along the road that source water from the school. A water truck plies this route. There have been talks, she said, about the village benefiting from potable water as pipelines have been installed already. Agatash is electrified.

Three buses provide the necessary transportation services at the cost of $100 for schoolchildren and $200 for adults going or coming from Bartica. Sundays and holidays are their rest days and taxis come at a cost of $2,000s.

Griffith is hoping for the development of the road and the village’s agricultural potential. “The land was leased as agricultural and residential. The hardest part with agriculture is getting the youths to get involved,” she said.

Beverly Fernandes stood under a shed chatting with relatives and neighbours. She moved to Agatash in 1985. She hails from Karrau situated minutes away from Bartica.

“When my mother died, my big sister moved here with her family. She took care of me and my other [siblings] after my mother passed. It was around then, when I came to live with her here. I lived here with her and then moved and came back. The village has changed a lot from then to now. There was no road then, just a track through the bushes. I remember me and my children clearing the place by hoe,” she said. Fernandes gave birth to 19 children; only nine are alive.

“I like the quietness, the river, the breeze. Everybody here live like family. Long ago we struggled for years. Before the road I used to walk with my big belly to the clinic in Bartica. There was no bridge then, I walked across the creek on a post. The grass used to be high over your head. It was a 45-minute walk. My big daughter after she finished primary school, had to leave the village to go to secondary school. We used to give she half an hour to reach home because we used to say you never know who is in the grass.”

Fernandes shared that at one point she was somewhat of an introvert but chose to improve herself by attending adult educational classes with her youngest daughter. She took up sewing and cooking classes and would sew uniforms during the August vacation and costumes for Mashramani. Currently, she is also a cleaner at the Agatash Primary School. The woman said that since last year the cleaners were expecting a raise of pay but to date nothing has become of it.

Fernandesy also works with the Policing Group in the community. She stressed that some of the youths have taken up drugs and are engaging in such activities in the presence of the smaller boys. Something needs to be urgently done about this the woman had said. She pleads for a vocational centre where the young men can better themselves.

“We also need for our health center to have the necessary drugs. Sometimes we don’t get Panadol or cold syrup for the children. We waited months for drugs and only the other day we get drugs. We can’t even get malaria or dengue tested here. We want a doctor and a certified pharmacist in Agatash,” Fernandes said. It was noted also that the overcrowded school is in dire need of an extension.

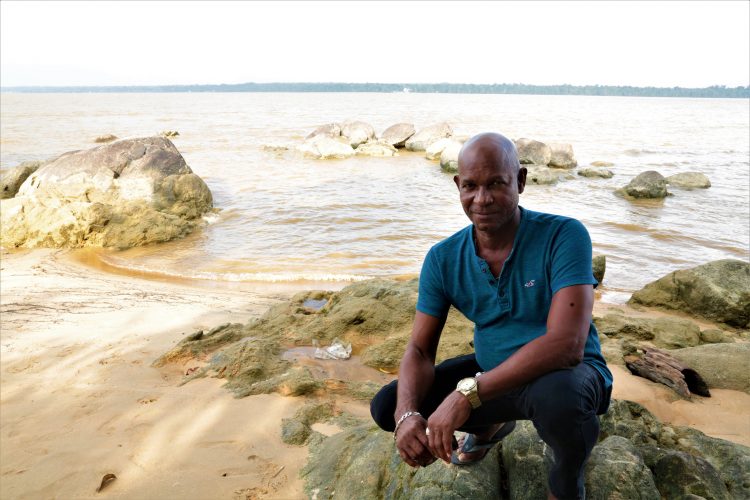

Glendon Fredricks was enjoying the afternoon with a friend when we met. He is a registration officer for the Guyana Elections Commission in the sub-region.

“Before this road was built this was originally an Amerindian village. You had to seek permission from the village leader before you visited,” he related. “After the road was built people began moving here to live,” Fredricks said.

He was one of the first teachers at Agatash Primary. He taught alongside the then headmaster, Carl Clementson. He began teaching at 17.

“My most vivid memory here was my grandma always telling me not to come to this part of Agatash [beyond the cemetery) after dark, because the kanaima would catch us or if you use the beach the massacooramaan would catch us. Some of it would have been related to the cemetery but her main objective was to keep us home after dark, but we didn’t always listen,” he said. This wasn’t the only time Fredricks didn’t listen. He was also warned to not swim around the Molasses Rocks. These are a particular set of boulders in the Essequibo River that are taboo, because of some drownings. He recalled three children losing their lives during his lifetime. At the end of the rocks, he said, there is a drop off that many persons don’t know about. He had his own experience which almost cost him his life. He was 9 at the time he went under but was saved by a pregnant villager. Fredricks claimed to have been careful after that.

Some of the village’s benefits he boasted about were the clean air and how considerate the people are of the environment. The only pollution, he said, was from dust raised by passing vehicles. A better road would fix this, he said.

He spoke of the dumpsite in Byderabo – Byderabo is on the way to Agatash – which is an eyesore to those who have to pass it every day. Another resident also spoke about the dumpsite and how much it affects passersby.

Fredricks concluded, “… We have a playground that is situated on a hill. It’s used every day. Agatash has its own football club and the guys would compete locally.”