During the five years that the Norway-funded REDD+ (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation) project ran, Guyana recorded 35% less deforestation than it would’ve without the project, Anand Roopsind, a Guyanese PhD student from Boise State University, says.

Roopsind, who has worked with Conservation International – Guyana (CI-Guyana) as well as with the Guyana Forestry Commission (GFC), presented the findings of his PhD study yesterday afternoon at the GFC, where he said that the REDD+ project resulted in 35% less deforestation over the 2010-2015 period, which amounts to approximately 12.8 million tonnes of carbon dioxide not being emitted into the atmosphere.

Roopsind’s study explored at what logging intensities would reduced impact logging (RIL) practices maintain the timber and carbon services that Guyana was being compensated for. “Guyana is super unique because we have one of the longest experiments running in the world on reduced impact logging,” Roopsind said, while noting that the study has been ongoing for more than 20 years and has been using an experimental design.

This design, he explain-ed, is needed to inform forest management in Guyana and includes several levels of logging intensities from what is codified in the GFC’s practices.

According to Roopsind, he found that if we log our forests using the best practice of four trees per hectare, then they will be able to recover both carbon and timber services within a 30-year cycle. He said this is already cemented in the GFC’s practices and is in line with what is being implemented in the country.

“Unfortunately, if we increase our logging intensity above eight trees, we start losing some of these benefits, specifically timber. Timber does not recover in a 30-year cutting cycle when we exceed our annual allowed cut, but we still have a lot of carbon so it’s still valuable,” he observed.

Even when the commercial species were liberated by removing the non-commercial species, there was a trade-off where more timber was gained but timber services were being lost, he said.

The question of how logging affects biodiversity as it relates to large mammals was also examined and Roopsind said what the study found was that the synergy of logging and hunting restrictions, along with other factors, resulted in there being no effects of logging on the large mammals.

As it related to reaching the conclusion in relation to deforestation, Roopsind said, there were challenges since there was no empirical data from other similar countries as they did not have a similar forestry management programme running for five years.

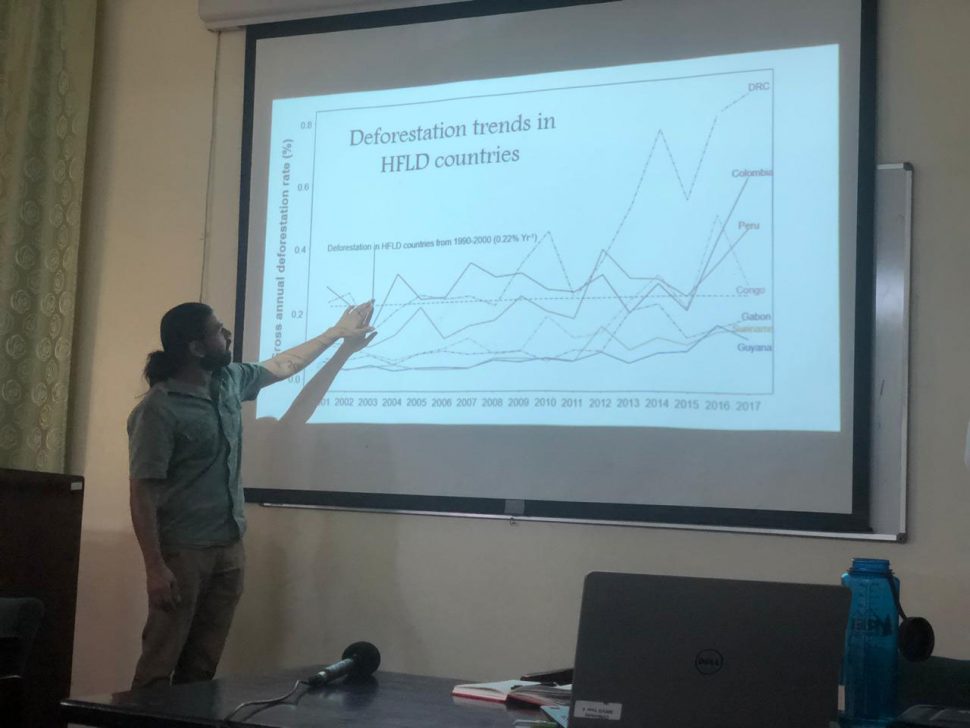

However, using satellite data images over a number of years, his study was able to map the forest cover for the entire world and also identify six countries – Peru, Suriname, Colombia, Congo, Gabon and the Democratic Republic of Congo – that have similar economic variables as Guyana.

“And so, because of that availability of satellite imagery, we can calculate the time series trajectory of all of those countries in terms of forestry loss…Guyana has always been consistent and below the threshold of what is considered as low and the concern here is that since 2011, there has been a huge spike across all of these countries and actually in 2017, it was the worst year in tropical forest loss in the world,” he said.

Of the six countries, Roopsind was able to identify the two most similar to Guyana – Suriname and Gabon – and was able to use the data garnered to create a scenario for Guyana without the REDD+ project.

“As soon as the agreement came into effect, our actual deforestation was substantially lower than it would’ve been without the agreement. So for the 2010 to 2015 period, Guyana’s actual deforestation is actually 35% less than what it would’ve been without the REDD+ agreement. That’s basically equivalent to 12.8 million tonnes of carbon dioxide that was not emitted into the atmosphere,” he explained.

Roopsind also pointed out that the price of gold also influenced the deforestation rate and when gold prices went up, the deforestation rate would move parallel to that.

He noted also that there could have been leakages across the bordering nations, such as Suriname but said this could be fixed by a regional approach with the setting up of management protocols for the forests along the Guiana Shield.

There was a discrepancy between Roopsind’s data for 2016 and 2017 when compared to the figures from the GFC, but he explained that the datasets used (satellite images) were constant along the countries that the study considered as compared to the dataset used by the GFC that only covered Guyana’s forest and for a 24-month period, as compared to the study which considered the data for each year.

Other points were also raised during the presentation as it relates to other factors that resulted in the low levels of deforestation, including the inadequate infrastructure and roads that lead into various concessions. It was also highlighted that as the roads’ conditions worsen, loggers and miners alike are less inclined to try to access their concessions which also has lasting impacts on the economy.

Attending the presentation yesterday were representatives from the GFC, including Chairman of the Board Jocelyn Dow, representatives from CI-Guyana, Iwokrama and other stakeholders.