In this week’s column, I begin consideration of Guidepost 6, as listed in my Guyana Petroleum Sector Road Map, for the dimension of “getting petroleum revenues.” This is the last Guidepost for that dimension.

Indeed, this particular Guidepost represents the metric that best expresses the anticipated cost-price relation for Guyana’s crude oil production. It is, therefore, central to the generation of profit (and hence revenues) from this activity, under Guyana’s existing petroleum licensing arrangements with international oil companies (IOCs).

From the perspective of this metric, the starting point of my presentation is best expressed in a foundational theorem of standard economics. That theorem indicates the rate of profit obtained from Guyana’s commercial production of petroleum is, broadly, a function of the value difference between the average total costs of production and the average realised price from all sales. Total profit in any period, therefore, is a function of the rate, times volume of production/sale.

Marginal Cost and Price

Standard economic theory also posits that, if crude oil was traded in a perfectly competitive global market, then its global equilibrium price is equal to its marginal cost of production. In other words, if the marginal cost of producing a barrel of crude oil worldwide is US$30, then the ruling equilibrium price in the market is also US$30. However, markets for crude oil are not by any means perfectly competitive. Readers, I believe, would readily acknowledge the truth in this observation. Therefore, I do not need to expand much how that would be possible, given: 1) the existence of cartels in today’s global market, (like OPEC), which regulate supply; and 2) the dominant role geopolitical and security considerations exercise over both the global demand for, and supply of, crude petroleum products.

For what it is worth, though, I reference here, solely for readers’ guidance, the fact that there are research companies, which collect and sell data on the marginal cost of crude oil per barrel (and relatedly also other energy products). One such firm has revealed that, in a recent sample of 17 countries during 2014, 1) 11 of these countries had a marginal cost of US$20 or less; 2) three had marginal costs below US$10; and, finally, 3) the range in the marginal cost for the 17 producers is from a low of US$3 to a high of US$80 (if we exclude Russia’s Artic frontier production which is far higher)! (Source: Knoema.com, 2019).

Unit Cost Determination

Before offering specific estimates of Guyana’s unit cost of crude oil production, I need to clarify for readers one further matter, which is entailed in estimating cost. This feature makes it very difficult to fix this cost 1) before crude production and sale even commences, and 2) in the absence of cooperation from the IOCs.

As a matter of strict economy theory, if there is no reliable/accurate information on the life-cycle of the intended wells supplying Guyana’s crude, no one is in a position to offer an accurate depiction of the cost of such crude production. The “rule-of-thumb,” which is standardly applied in the petroleum industry, is that the “life-span of onshore oil and gas fields (from first oil production to well abandonment) ranges from 15 to 30 years.” As I have previously noted, for deepwater fields the rule-of-thumb is a range around 5 to 10 years; that is, one-third of onshore fields. The rationale for this significant difference is the high exploration and extraction costs of deepwater wells. Readers are familiar with this circumstance. However, similar information for ultra-deepwater fields (as are some in Guyana) is scant. Experienced analysts do not confidently offer/predict a “reliable” rule-of-thumb for use in such petroleum fields.

These considerations that are attached to the life cycle of intended wells for supplying crude, apply also to the broader notion of petroleum projects. Indeed, this is the manner in which these considerations would emerge to affect the estimation of cost of production for Guyana’s crude oil! This concern is therefore addressed in the next Section.

Before that, however, I need to respond to the query: What is a petroleum project? In petroleum economics, “petroleum projects link petroleum accumulation and the decision-making process, including budget allocation” (World Petroleum Council, Petroleum Resources Management, 2007). As I had previously observed (April 29, 2018) a petroleum project can represent either: 1) a single well; 2) a field with several wells; 3) an incremental development in an already producing field or reservoir; or 4) the integrated development of a group of fields or reservoirs. Typically, projects are advanced to levels where decisions to proceed on them or not, with spending money, are made.

The Life Cycle

Given the above circumstance, the life cycle of a petroleum project is integral to the accurate determination of its cost of production. Further, this cost varies over the project’s life cycle, and so do prices, cash flow, and, therefore, profitability. An understanding of the life cycle concept is consequently central to any rational appraisal of the performance and cost of petroleum projects.

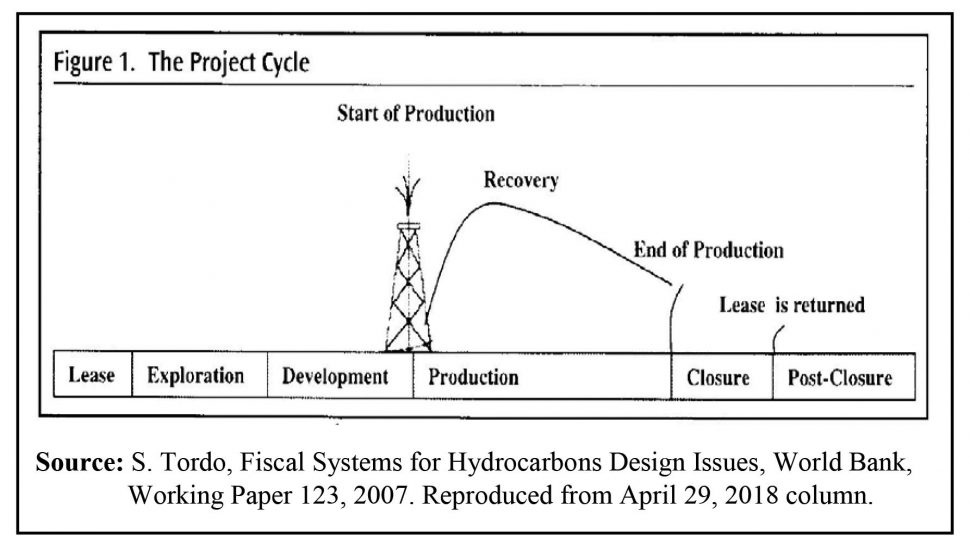

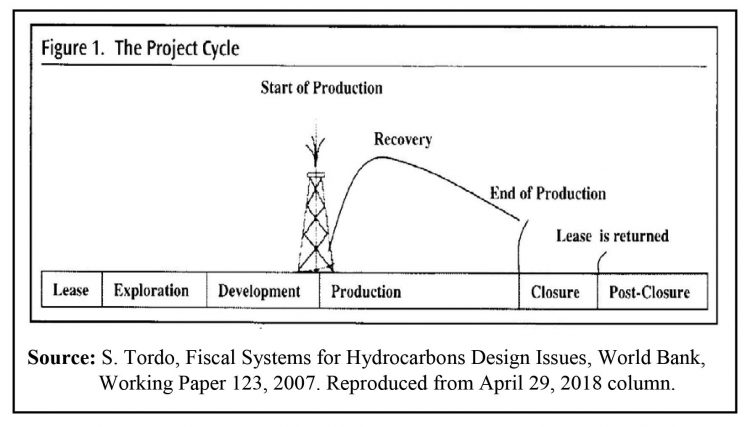

Finally, energy economics texts portray the petroleum life cycle as having six distinct stages. (These are succinctly identified in Figure 1). Over these six distinct stages, the risk-reward or cost-price-profit profile of the project changes. Such risks typically comprise three core elements; namely, geological, financial and political. As a rule, however, geological risks tend to diminish progressively as petroleum finds and discoveries are made. However, the latter two risks (financial and political) can, in practice, multiply! It should be noted also that such changes alter the risk-reward (cost-price-profit) profile, as well as the balance of negotiating power between the GoG and the IOCs.

Six Stages

The six project (cost-price-profit or risk-reward) stages are: 1) the lease-licence-permit stage; 2) the exploration stage after acquiring rights; 3) the appraisal and preparation of development plan stage; 4) the production stage (from startup-ramp up-to full capacity production/decline); 5) the closure or end of production phase; and 6) the post-closure of production phase. These data are shown in Figure 1.

Conclusion

Next week, I proceed from this introductory presentation of what is involved/required for estimating the cost of production of Guyana’s crude as indicated by Guidepost 6, in the Road Map dimension of “getting petroleum revenues.”