When in the early 1990s it became apparent that Europe’s preferential regimes for Caribbean bananas and sugar were coming to an end, an impassioned debate began about a transition to other forms of economic activity.

When in the early 1990s it became apparent that Europe’s preferential regimes for Caribbean bananas and sugar were coming to an end, an impassioned debate began about a transition to other forms of economic activity.

For the most part, the focus was on alternative crops, import substitution, manufacturing, and financial services. Little was said at the time about tourism because its sustainability was widely regarded as uncertain.

Since then the world has moved on. Tourism has come to dominate most Caribbean economies. Unconstrained by the region’s smallness, the internet has enabled new offshore services to develop and prosper, and financial services, after being encouraged, have come under threat from the same nations that promoted their development.

In contrast, agriculture has been slow to reorient itself.

While some entrepreneurs in the sector moved on and identified niche domestic or export markets or saw opportunity in large new acreages on virgin land on the mainland of South and Central America, most Caribbean farmers have remained caught in the past. Moreover, agriculture’s low returns and economic and climatic uncertainties have made the sector unattractive to most young people, resulting in there being little new thinking about how as an industry, agriculture should adapt to a much-changed Caribbean.

For this reason, a just published Caribbean Development Bank (CDB) and UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) ‘Study on the State of Agriculture in the Caribbean’ is a breath of fresh air as it outlines how, with a significantly changed approach, the sector could again become of much greater economic and social relevance.

What it does is provide a long overdue comprehensive analysis – incredibly, the first since 1981 – of agriculture in all CARICOM states, including Haiti, plus the UK’s five Overseas Territories, which together comprise the Bank’s nineteen borrowing member countries.

It notes that while Dominica, Guyana, Haiti and Suriname remain heavily dependent on agriculture, with the sector accounting in these nations for between 12% and 17% of GDP and between 10% and 50% of employment, in ten other borrowing nations, agriculture now accounts for less than 4% of GDP.

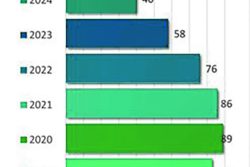

The study confirms that since 2000, the food import bill of CDB’s borrowing members has more than doubled from US$2.1 billion to US$4.8 billion, with imported food now accounting for 60% of the food consumed in CARICOM and the UK Overseas Territories. It also says that in its borrowing countries, food exports of traditional crops fell from 60% of agricultural production in 1990 to less than 20% in 2018.

As well as focussing on how the economies of the region have changed and how Caribbean agriculture might adapt, the study identifies the steps required to resuscitate the industry and reduce the region’s huge food import bill.

CDB made clear that the principal challenge now facing agriculture in the region is improving competitiveness and productivity. Productivity growth in Caribbean agriculture, it observes, remains low, with value per worker per annum remaining largely unchanged for 30 years. This, the report notes, contrasts negatively with Europe, where over the same period the value has doubled or, in the case of the United States, tripled.

CDB also said that because the sector has only a limited ability to comply with modern food safety and quality standards and for the most part lacks irrigation, it has been unable to adequately respond to the region’s rapidly growing demand for high-standard, agri-food products for the tourism, food processing and retail sectors, either within or beyond the region. The consequence has been a growing demand for agricultural imports.

Despite this, the report, which also addresses fisheries and aquaculture, says the sector as a whole has great potential for the creation of stronger market linkages with sectors such as tourism, if support is provided to farmers, fisherfolk and agri-food businesses to adopt current international best practice and technologies.

CDB’s intention now is to develop a new agricultural policy and strategy paper for governments, multilateral institutions and aid donors, with the intention of modernising Caribbean agricultural practices, identifying key trends and the innovative practices and the science necessary to support an integrated approach. It also intends proposing measures that incorporate technology across the value chain and strengthen the sector’s capacity to become more resilient to climate change.

What makes this report particularly important is that it is forward looking, outlines solutions and opportunities and gives hope to all who believe in the centrality of agriculture to Caribbean life and who want to restore respect for agriculture’s role.

If the Caribbean’s agri-food system is to become more competitive, inclusive and sustainable, it has long been self-evident that agriculture requires a new approach, new policies and investment. In particular, as a sector, it needs to overcome its inefficiencies, adopt best practice and see more resources and much more land under crops that offer greater value to farmers and consumers.

Well delivered change could again make agriculture, albeit in a very different form, an important source of future regional economic growth and see the sector become a key contributor to poverty reduction, particularly for those not able to benefit from growth in other parts of the economy.

As CDB suggests, a resuscitated and integrated industry could also help address the socio-economic problems that the region faces in relation to food and nutrition insecurity, obesity, youth unemployment, and gender inequality.

By illustrating quite how much there is to be done the reports begs the question as to who is going to act and how quickly.

In recent years, CDB has developed a reputation for well thought through and executed actions. It has gained renewed respect from its lenders and non-borrowing members which include the UK, China and Germany and is well placed to mobilise resources.

However, initiating a new public-private policy dialogue, increasing acreages, addressing overfishing, identifying value chains, developing transport links to regional and overseas markets, and all else that is required to reinvigorate Caribbean agriculture will necessitate a well-integrated, managed and sustained effort with substantial resources delivered over a long period.

Transforming Caribbean agriculture in a manner that ensures it has a sustainable long-term future may be complex but pales in comparison to the social and economic cost of inaction. The CDB report indicates this clearly and that if adapted, agriculture has an important role in the region’s future development.

David Jessop is a consultant to the Caribbean Council and can be contacted at david.jessop@caribbean-council.org

Previous columns can be found at https://www.caribbean-council.org/research-analysis/