(This is the fifth in a series of articles by Transparency Institute Guyana Inc on the Production Sharing Agreement signed between the Government of Guyana and Esso Exploration and Production Guyana Limited, a subsidiary of ExxonMobil.)

In our last article we presented facts that suggested that the claimed need for Exxon as insurance against Venezuelan hostility to justify the breach of the 60-block maximum per contract was an overstatement to use the most polite word. Today we discuss alternatives to that action taken by the then minister and supported and maintained by the current minister. We also provide comparative information for readers to get a better understanding of the areas included in a single licence. Of course, these areas are the foundations of the contracts in the various territories. Their borders dictate where other licences begin. In the case of Guyana, the enormous size of the area over and above the company’s legal entitlement is an area from which Guyana is locked out under the “contract” with Exxon.

Sum of the parts much better than the whole

Mr. Trotman said what was needed was “tip to tip” control from Barima-Waini to the Corentyne for “security reasons” (Gordon, May 19, 2018 in Guyana Chronicle). We contend that handing out such a large area of seabed in a single licence was unnecessary. Keep in mind that the path taken was to bundle what should have been several individual licences into one licence governed by a single contract which we have nicknamed wholesaling.

The ministers could have achieved the same purpose by sticking to the law and rotating the relinquished areas among the same players who are in place now or any others that might be in Guyana. In other words, licence blocks held by Exxon could have been licensed, for example, to Cnooc upon relinquishment then to Hess on a continuous basis. There was no need to utilize this curious device which we found in no other part of the world. We are unable to explain how this could have escaped the minds of persons who occupy the highest positions in the land.

Comparison of licence block size

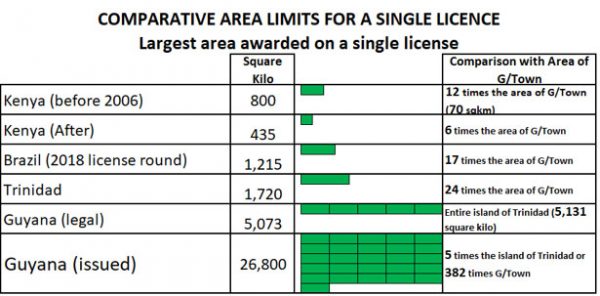

Here diagrammatically is a comparison of block size so readers can get a better idea. Comparisons are made to the sizes of Georgetown [70 sq km] and of Trinidad [5,131 sq km].

The legal and issued areas in Guyana are segmented to facilitate more detailed comparison.

Gold shout

As is well-known in Guyana and all over the world, if gold is discovered in a claim, there is a high demand for the nearby blocks. What the issuance of this huge tract of seabed under a single licence did was to ensure that there were no “nearby” blocks for the people of Guyana to benefit from as happens elsewhere when companies have to bid for those blocks.

Valid Special Circumstances

In our previous article we set out what are admissible special circumstances. For example, if part of a nearby licence block has been surrendered and manages to leave a piece of, say, 15 graticular blocks stranded nearby, and no investor is interested, the minister may attach that 15-block area to an adjacent area. There should then be a new map indicating to all investors that that piece of 75 blocks (60 blocks as the legal limit plus the 15 stranded blocks) is available as a complete package.

Given what DPM Murray said about the new investment policy: “This set out very clearly the ground rules under which foreign investors could and would operate” (see Watson & Craig, 1992, p. 5; see also TIGI in SN June 12, 2019) it is surprising that a minister would not know what are admissible special circumstances. After all, the 1986 Petroleum Act conforms to a template used at that time, and which is still recognizable in all countries with a petroleum policy. The salient features of the template are definition of the basic graticular block in terms of latitude and longitude, publication of a map showing the blocks available for licence, requirement to relinquish after a number of years to avoid indefinite squatting on valuable seabed, and a maximum number of graticular blocks that can be issued on a single licence (with no limit to the number of individual licences that can be issued to a single company).

Territorial disputes

In his paper titled Oil and Gas Development in Disputed Waters Under UNCLOS, Constantinos Yiallourides points out that “It would not be unreasonable to say that most of the world’s maritime boundary conflicts have been resource-induced, most commonly by the known or suspected presence of mineral and fossil-fuel deposits lying in areas over which two or more coastal States may claim control and jurisdiction” (Yiallourides, 2016, p. 59). In recent times we have Kenya and Somalia, Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, Australia and East Timor, and in the Mediterranean the threats of Turkey over the operations progressing there. We could add to the list the dispute between Barbados and Trinidad & Tobago which complicated oil exploration in the region. This claim was settled in the Hague in 2006.

What is truly remarkable is that we could find not one country other than Guyana which has found it necessary to go so far as to break its own laws to purportedly entice an oil company (let alone attempt to enshrine the illegality in a new “contract” after oil is discovered). Not one of them has found it necessary to use this curious device which presents to an oil company the opportunity which the country itself should have had to auction the nearby blocks.

Force Majeure clause

Perhaps there is no greater evidence that, at the time of signature of the contract in 1999, protection by Exxon from Venezuelan belligerence could not have been in the minds of the signatories than the wording of the contract itself. We refer to the force majeure clause.

USLegal provides this definition of force-majeure: “Force Majeure clause is a provision in a contract that excuses a party from not performing its contractual obligations that become impossible or impracticable, due to an event or effect that the parties could not have anticipated or controlled. These events include natural disasters such as floods, earthquakes and other “acts of God,” as well as uncontrollable events such as war or terrorist attack. Force majeure clauses are meant to excuse a party provided the failure to perform could not be avoided by the exercise of due diligence and care” (USLegal Inc., 1979 – 2019).

Government functionaries, past and present, tell us that the special circumstances justifying the decision to breach the 60-block maximum was Venezuela and that as a result they needed a heavy-weight like Exxon to provide security for the operations in the area. That should mean that a) Venezuelan hostility was anticipated, and b) the selected licensee would provide the appropriate security services.

But Clause 24.2 of the 1999 contract took the trouble to provide as follows: “In this Article, the term “force majeure” … includes … wars declared or undeclared, hostilities, invasions, …, international disputes affecting the extent of the contract area …” This was a clarification of S43(3) of the 1986 petroleum act which indemnifies the licensee against “… act of war, hostility, insurrection, …”

The contract goes on to provide that “… the Minister may refuse to agree to the addition of any period to the term of the licence if the licensee could, by taking any reasonable steps which were open to him, have exercised those rights during that period notwithstanding any such occurrence.”

Since Esso responded to subsequent hostile action, including from Venezuela, by retreat, evasion and activation of its right to add additional time to the license period, all with agreement of the Government of Guyana, we can safely conclude that a), Esso was expected to do exactly nothing but wait out the interruption and b), was not expected to provide any kind of security whatsoever. Had security against Venezuela been part of the agreement one would have expected that Esso would have taken those “reasonable steps” whatever they might be in such circumstances.

In fact, not only did Exxon not demonstrate anything but an evader role during Venezuelan activity in the West, but the rationale for its activation of the right under the clause was not even Venezuelan activity, but from a much smaller power – Suriname. Exxon claimed the right to activate this clause on account of the eviction of the CGX rig effective from 2000 – just one year after the 1999 contract was signed.

Conclusion

We believe that we have provided enough evidence to conclude that the claim that Esso was expected to provide some kind of security against Venezuela was most likely mainly a projection into the past for purposes of justifying this strange arrangement and that it has no basis in reality.

The facts we have assembled expose the minister’s use of discretionary power to stretch a maximum beyond recognition for a reason that is suspect at best, absurd, brazen and worst of all, unnecessary.

In our next article, we address what is probably a greater and more fundamental flaw in this “contract” if that were possible. It is an omission that affects all petroleum contracts (Exxon and subsequent). This omission on its own, renders every single one of them illegal, and exposes the unseemly haste with which whatever remaining seabed was disposed of, in the face of all advice from qualified Guyanese and the IMF to await improvement of the legal framework.