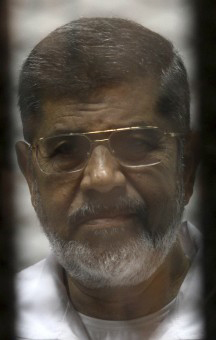

CAIRO, (Reuters) – Former Egyptian President Mohamed Mursi, the first democratically elected head of state in Egypt’s modern history, died yesterday from a heart attack after collapsing in a Cairo court while on trial on espionage charges, authorities and a medical source said.

The 67-year-old Mursi, a top figure in the now-banned Muslim Brother-hood, had been in jail since being toppled by the military in 2013 after barely a year in power, following mass protests against his rule.

His death is likely to pile up international pressure on the Egyptian government over its human rights record, especially conditions in prisons where thousands of Islamists and secular activists are held.

The public prosecutor said Mursi had collapsed in a defendants’ cage in the courtroom shortly after addressing the court, and was pronounced dead in hospital at 4:50 p.m. (1450 GMT). It said initial checks had shown no signs of recent injury on his body.

The Muslim Brotherhood described Mursi’s death as a “full-fledged murder” and called for masses to gather at his funeral in Egypt and outside Egyptian embassies around the world.

Mursi’s family previously said his health had deteriorated in prison and that they were rarely allowed to visit.

A medical source said Mursi died of a heart attack.

The source said Mursi, who was diabetic and suffered from high blood pressure, had received medical treatment at a private hospital and at the police hospital in Cairo, denying that he was deprived from medical attention.

Mursi’s son, Abdullah Mohamed Mursi, told Reuters that the family had not been contacted about the details of the burial and were only communicating through their lawyers. Abdullah said earlier that authorities were refusing to allow Mursi to be laid to rest in the family burial grounds in his native Nile Delta province of Sharqiya.

“We know nothing about him and no one is in touch with us, and we don’t know if we are going to wash him or say a prayer to him or not,” he said.

Amnesty International called for an “impartial, thorough and transparent” investigation into Mursi’s death.

“Egyptian authorities had the responsibility to ensure that, as a detainee, he had access to proper medical care,” the group said in a statement.

A British member of Parliament, Crispin Blunt, who had led a delegation of UK lawmakers and lawyers last year in putting out a report on Mursi’s detention, slammed the conditions of Mursi’s incarceration.

“We want to understand whether there was any change in his conditions since we reported in March 2018, and if he continued to be held in the conditions we found, then I’m afraid the Egyptian government are likely to be responsible for his premature death,” he said in remarks to the BBC.

After decades of repression under Egyptian autocrats, the Brotherhood won a parliamentary election after a popular uprising toppled Hosni Mubarak and his military-backed establishment in 2011.

Mursi was elected to power in 2012 in Egypt’s first free presidential election, having been thrown into the race at the last moment by the disqualification on a technicality of millionaire businessman Khairat al-Shater, by far the Brotherhood’s preferred choice.

Mursi’s victory marked a radical break with the military men who had provided every Egyptian leader since the overthrow of the monarchy in 1952.

He promised a moderate Islamist agenda to steer Egypt into a new democratic era in which autocracy would be replaced by transparent government that respected human rights and revived the fortunes of a powerful Arab state long in decline. But the euphoria that greeted the end of an era of presidents who ruled like pharaohs did not last long.

The stocky, bespectacled engineer, born in 1951 in the dying days of the monarchy, told Egyptians he would deliver an “Egyptian renaissance with an Islamic foundation.”

Instead, he alienated millions who accused him of usurping unlimited powers, imposing the Brotherhood’s conservative brand of Islam and mismanaging the economy, all of which he denied.