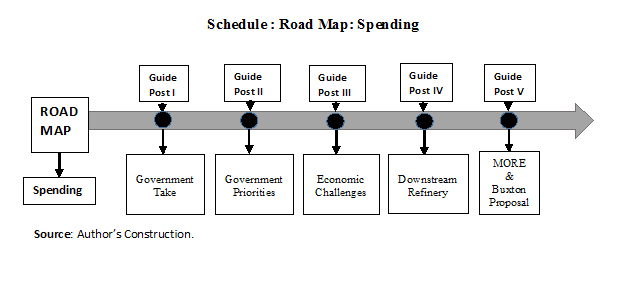

This week’s column starts my presentation of the Second Part of Guyana’s Petroleum Road Map. It deals with “government spending of its petroleum revenues.” For this dimension of the Road Map, there are five main Guideposts; namely: 1) Government Take; 2) Government spending priorities; 3) Economic challenges; 4) Downstream value-added expenditures; and 5) Establishing a Ministry of Renewable Energy (MoRE) and my so-called Buxton Proposal. These Guideposts were indicated earlier graphically (February 3, 2019) and, for convenience are reproduced in the Schedule below. They shall be addressed in the order given in the coming weeks

Here I basically wish to remind readers that the Road Map, as I have indicated, is a rudimentary construction. It is designed solely to illustrate the key strategic indicators for promoting the best use of Guyana’s coming oil and gas revenues. It is, therefore, not intended to be a detailed National Plan for today’s Guyana economy as it transitions to one dominated by its petroleum sector. By the same token, neither is it a simple “to do list of actions”

For today’s column, I offer a very brief overview of the five Guideposts for this dimension of the Road Map. I, therefore, take this opportunity to inform readers that the presentations, which follow, draw substantially on the extended analyses offered in Volume 3 of this ongoing series. These analyses were conducted over the long period: September 4, 2016 to January 20, 2019!

The “5” Guideposts

Guidepost 1 will be considered next week as a separate topic. Following the Schumburger’s Oilfield Glossary, Government Take is defined as “the total amount of revenue that government receives from production” (of petroleum products). Typically these products are crude oil and natural gas. And as such they are expressed in terms of barrels of oil equivalent (boe). It should be noted Government’s petroleum revenues include taxes and royalties, as well as incomes from government participation in production. In Guyana there is no National Oil Company (NOC) and therefore the last item does not apply.

Although only taxes and royalties are referenced in the definition above, all relevant fiscal rules affect the size of Government Take; for example, cost recovery provisions, agreed payback periods, and profit split provisions contained in the relevant oil contract. Two other observations are worth noting at this juncture.

First Government Take is not the same as the economy’s foreign exchange and local earnings from the sale of petroleum products. These earnings, as a rule, far exceed the Government Take. Second, as I have previously indicated it is incorrect to portray Government Take and the Contractor’s Take as a zero sum relation. That is one in which either party’s share is only at the expense of the other!

Finally, studies show an extremely wide variation in this ratio across countries and regions. This will be looked at next week.

Guidepost 2 refers to Government’s publicly stated priorities for its spending of expected petroleum revenues. Based on their electoral mandate, I believe every representative government has both a right and duty to operationalise its spending priorities in this circumstance. The task of this second Guidepost is therefore primarily to identify these priorities and to provide the reasoning behind my choice of each priority identified.

I shall identify these priorities from: 1) Government’s documented strategic development priorities; 2) Government’s National Budgets (recent); and 3) Government’s already commenced implementation measures in preparation for its coming time of petroleum production. I feel confident these three items will do justice to the content of this Guide.

Guidepost 3 refers to the top 10 macroeconomic/developmental challenges developing a petroleum sector poses. I had analysed these at great length during the long period from Sunday July 1, 2018 to Sunday January 6, 2019. As indicated back in my July 1, 2018, column, these challenges are: 1) what is termed the threat of Dutch Disease; 2) the burdens of the Resource Curse; 3) the dangers of the Governance Curse; 4) the lack of sufficient Absorptive Capacity; 5) the entrenchment of an Enclave Economy; 6) the persistence of Implementation Lags; 7) the maintenance of Intergenerational Equity; 8) International Financial Institutions pressure on governments to spend on the basis of the Permanent Income Hypothesis; 9) the requirement to Manage Public Expectations; and last but by no means least 10) the necessity to Integrate the Petroleum Revenues into the National Budget process. I had analysed each of these challenges in the columns indicated above.

Guidepost 4 refers to matters related to seeking to increase value-added to the production of crude oil and natural gas in Guyana upstream. Value-added simply means turning Guyana’s crude oil and natural gas into other usable products, thereby adding value to its petroleum reserves. This would lead to diversification of output and, if exported, could lead to the diversification of exports, sources of foreign exchange, and even foreign investment. Of course, such activities also support employment creation.

Guidepost 5 details my two foundational spending recommendations. First, based on my judgement that Guyana’s petroleum reserves potential is formidable both per person and absolutely. I shall argue its renewable energy resources are, potentially, just as formidable. Given this, I propose that a specialised Statutory Body or MoRE is created

Second, I call for spending Government Take, to make cash transfers (conditional and unconditional) to Guyanese households. This has become known as the Buxton Proposal, which I had made public last August, at a Symposium held in commemoration of the 2018 Emancipation of Slavery. This proposal had identified a target annual cash transfer of G$1,050,000 or US$5,000 per household, at the full ramp-up of petroleum production.

Both these investments represent, strategically, the best economic/developmental way for spending Guyana’s Government Take. I shall argue they provide a transformational outcome for Guyana’s economy, which is the ultimate goal of the Road Map.