By Nigel Westmaas

In a long search through public records, newspapers, books and other sources over several years, I managed to unearth, at last tally, roughly 95 plus “formally announced” political parties from the Dutch colonial period right until the present. The overwhelming majority of these political parties only enjoyed very short life spans. These ranged from the “Citizens Party” to modern parties like the PPP, the PNC and the AFC. Except for the PPP, PNC, UF (TUF), and WPA (and closing in, the AFC), it would be fair to say that none among the approximately 95 political parties throughout Guyanese history were proactive for more than two decades.

But there is a deep, wider legacy of political organisations and political actors that barely make mainstream discussion or reflection on this country. Expectedly, there will be subjective inputs and controversy about the type and size of political organisations that prevailed throughout Guyanese history. Kimani Nehusi’s newest tome, “A Peoples Political History of Guyana 1838-1964,” offers its own wide-ranging examination of a longish clutch of Guyanese history afforded by new material and more detailed and critical eyes on mainly the late 19th and early 20th century political organisations.

Early political party formation

All political parties materialise in certain contexts. The early 20th century Guyanese historian PH Daly identified the colony’s first political party as the “Citizens Party,” led by Joseph Bourda of the late 18th century. A second early political organisation, the Planters Party (whose very title ratifies its backing of the plantocracy), appears to have had diverse names, and over a period lasting from its origins in 1871 to the early 20th century, was known alternately as BG Planters Association and Planters Association, the latter of which competed against the People’s Association in 1911. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the raison d’etre for political formations was almost always predicated on attempts to widen the franchise, expand the restricted colonial directorates or policy-making bodies and to agitate for myriad economic and social causes in colonial Guiana.

The early political parties emerged during the struggle for an expanded electorate in governing bodies previously dominated by the plantocracy or colonial political institutions. These fora included the Court of Policy, the Combined Court and the electoral college of Kiezers, the latter dispensed with in the 1890s partly as a result of middle-class agitation. As Nehusi points out, “the struggles, ultimately mainly for greater middle-class economic emancipation, took the form of political struggle, aimed at middle-class admission into the formal political process, the winning of elections, and eventually the passing of laws to protect and foster the interests of the would-be political power.”

Political party history in Guyana, like elsewhere, has the dilemma of determining conceptual and “activity standards.” How do we assess the viability of a political party? It is always confounding to measure or ascribe status, in size and support base (and impact) to a new political party, past or present. In Guyana, there were several cultural-ethnic organisations that were “political” in general terms but were never classified as political parties. For example, in the early 20th century, colonial Guyana witnessed the rise of the British Guiana East Indian Association (1919), the birth of the Negro Progress Convention from 1922 (the latter growing to approximately 40 branches throughout Guyana at its height), and the emergence of Garvey’s Universal Negro Improve-ment Association (UNIA). Although the first two of the groups can be described as local ethno/cultural organisations, it would be a travesty to suggest these groups did not intervene in, and influence, political discussion and activity.

While the focus here is on political parties in Guyanese history, the broader socio-cultural context and local happenings are as imperative as any political party’s “ideology” and subsequent interaction and impact with society.

Political parties in the early 20th century, for instance, would have had to handle, or were shaped by, issues such as labour and poverty of the colonial denizens, adult suffrage, the scrap for an expanded franchise, the Seditious Publications Bill of 1919 (established to repress publications of movements like Garvey’s UNIA), the rise of labour unions, unemployment and the high cost of living, the many riots on plantations, rum shop closing hours, the struggle for shorter working hours, the indentured immigration debate, the effects of World War I on the colony, the effects of the 1911 census (for the first time the Indo Guyanese population was numerically the largest in the colony) on race relations, the colony’s budget, the discovery of bauxite, and the perennial road project to Rupununi, among other extant matters for the time. As far as political party intervention in this colonial period, a Daily Argosy report acknowledged the existence of three political parties in 1912—a “Government party, the Peoples party and Planters party.”

The formation of a new political party, “The Young Guianese Party,” was typical of the rise and swift demise of political organisations in British Guiana.

The Daily Argosy reported its founding on August 1, 1914, on the cusp of the outbreak of the First World War:

A largely attended meeting was held in the Independent Congregational schoolroom, New Amsterdam on Wednesday afternoon for the purpose of organizing the new political party whose propaganda will be to see that all men qualified to exercise the franchise are placed on the voters list; to make its members familiar with the political situation of the country and to carry an active political programme generally. The office bearers elected were Mr J Eleazar, chairman; Messrs. JZ Peters and T Boston, vice-chairmen; Rev RT Frank, treasurer, together with a large committee of management. Included in the programme will be quarterly lectures to be delivered by various gentlemen in the community who take an interest in the politics of the country. It was decided to christen the association as “The Young Guianese Party.”

The “Young Guianese Party” went on to contest general elections in 1916 with an undetermined level of success. It was not heard from again and some of its key leaders re-emerged in newer political entities or trade union leaderships.

Another party, the BG Political Association, established in 1912, ran aground rapidly, with the Daily Argosy in November 1914 listing it as “inactive due to funds.”

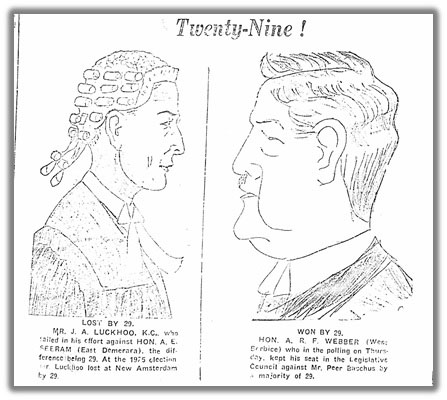

The organisation and title of the “Peoples Party” is a curiosity as it might have sprung from the famous Peoples Association and was said to mutate several times over, under different titles into the 1920s, and might even have coalesced with, or subsumed in an early 20th century politician ARF Webber’s Popular Party. At its height, the Popular Party contributed 7 elected members to the Guyana legislature before it became defunct by 1926

Were there any attempts to form a women’s political organisation? Only by way of individual female activists who were serving in both political parties and social organisations, while advocating for women’s rights. In 1930, a report in the Daily Argosy announced the “First woman in active politics” when Mrs H Glasgow became the first woman to serve on a local government board, in this case, Kitty. Other women, like Gertie Wood, fought for the expansion of the franchise, women’s rights and other issues on the labour front.

Albert Athiel Thorne, Barbadian born labour leader, journalist, politician, and educator, was a titanic figure in colonial Guyana for more than 50 years. Daly described him as “the tomahawk of Socialist Economics.” Daly said with Thorne, “Socialism has always been a life and death struggle, a sort of Bright’s Disease which develops great symptoms when Capital offers his beloved Labour terms sugared to a dialectical flavor.” Throughout his political career, Thorne was mainly active as an independent politician, seeking one or more of the seats available on legislative bodies in the colony.

A demographic of political parties over time

While space does not allow elaboration, in a summary breakdown of political parties by era and decade, it is noticeable that in certain periods or decades there were a greater number of political parties. For example, in the 19th century, there were approximately 7 political parties making an appearance; the 1920s witnessed the advent of approximately 4. In the 1950s, there was a surge in the birth of political parties, with around 15 recorded; in the 1960s, 10. The period of extreme political agitation against the PNC regime in the 1970s yielded only 3 political parties. The 1980s and 1990s saw the emergence of seven and ten political parties, respectively. From the 2000s to the present 14 political parties were listed, inclusive of the newly established parties like the ANUG, the FED-UP, and the Liberty and Justice Party.

In total, 18 political parties were not identifiable by year of origin or activity. Except for political title, these parties were characterised by relative silence on their formal arrival, period of activity, programme, or fate, and fleeting reports of their activity in the press. In the period after the Second World War, there was an efflorescence of political parties but this period was dominated by the events of 1953. While local and international attention was directed at the fortunes (or lack thereof) of the PPP, there was other political stimuli via parties that went largely unrecognised. Examples abound and are provided here in short sketches.

The Guiana National Party (GNP) was largely drowned out by the publicity accorded to the PPP of the 1950s. While members campaigned for the GNP, they contested seats as independents. The party was led by the highly respected rural physician Rohan Loris Sharples and popular school teacher Charles Clarence Bristol. Five members of this party were nominated for various rural constituencies.

The Guiana Rightist Party, led by Gool Sheer Rahaman, was founded in Bloomfield, Corentyne in 1956.

The United Democratic Party (UDP), also active in the 1950s, was led by the Afro Guyanese urban middle-class, including John Carter (later Sir John Carter) and finally merged its identity with the PNC.

The Guyana Independence Movement, of brief vintage, was established in 1958 and featured leader Narine Singh and chairman George Younge

The Progressive Liberal Party was founded in August 1959 and its leaders included Shakoor Manraj and Fred Bowman

The 1960s was another significant decade for the intervention of new political forces in both periods, pre- and post-independence.

Among the parties emergent in this decade were:

The Guyana United Muslim Party (GUMP). Formed in 1964, it emphasised its religious orientation and was led by Mohamed Hoosain Ghanie

The Guyana National Party was established in 1968 with Amerindian leadership. The party “failed to register for the 1968 elections,” according to one newspaper report.

In the 1970s, the Liberator Party, headed by Dr Ganraj Kumar and Dr Makepeace Richmond (Chairman), emerged. This middle-class-based party contested the 1973 elections.

What are the main takeaways of this record of political parties?

First, and logically, the activity of separate political parties in Guyana comprises the name of the organisation, the key leader or leaders, programme or initial political intervention, and of course, no declaration of dissolution if a party were to decline or die. If there is one consistent fact throughout time, political organisations rarely announce their own demise.

Second, political memory is very slender in Guyana. There is a general absence of a holistic sense of the country’s political history, including short-term historical memory. And an entire (modern) generation or two are quite likely presented with the impression that Guyana’s political history is generated and determined by the two main two political parties, the PPP and PNC, and their leaders.

Finally, it would be useful if our collective political memory of the legacy, that is, successes and failures of political parties of the past, could be actively retained in the public historical record, as sample and as caution, as the country lurches to one more general election.