Today’s column measures the impact of applying my values for production, price, and Government Take (indicated in Part 1 of Guyana’s Petroleum Road Map), to Rystad Energy’s analytics. Afterwards, selected concerns related to Government Take and Guyana’s Production Sharing Agreement (PSA) are addressed.

Rystad Energy Analytics

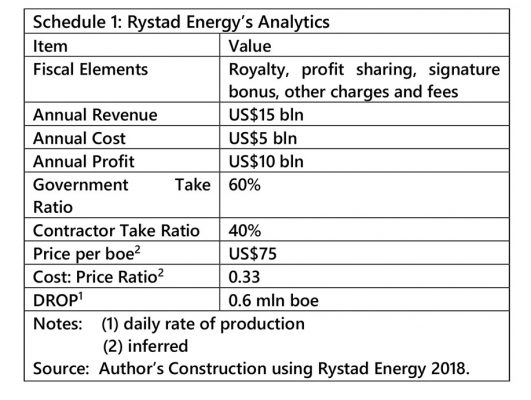

A year ago, Rystad Energy’s Research Department had forecasted for Guyana 1) a daily rate of production (DROP) of 0.6 million barrels of oil equivalent (boe), at full ramp-up and, 2) Government Take of 60%. From these two indicators, the firm projected annual revenue of (US$15 billion), and profit of US$10 billion; after all costs (US$5 billion) are deducted. Using these ballpark estimates, I deduced a cost/revenue ratio of 0.33 and price of US$75 per boe. These data are summarised in Schedule 1.

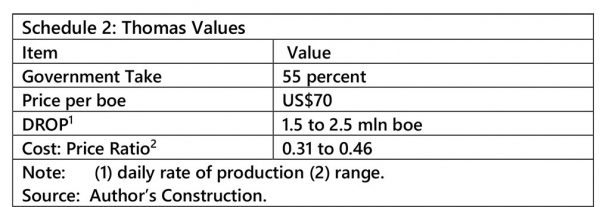

In Part 1 of the Road Map, I had projected a price of US$70 per boe; DROP of 1.5 to 2.5 million boe; and Government Take of 55% (see Schedule 2).

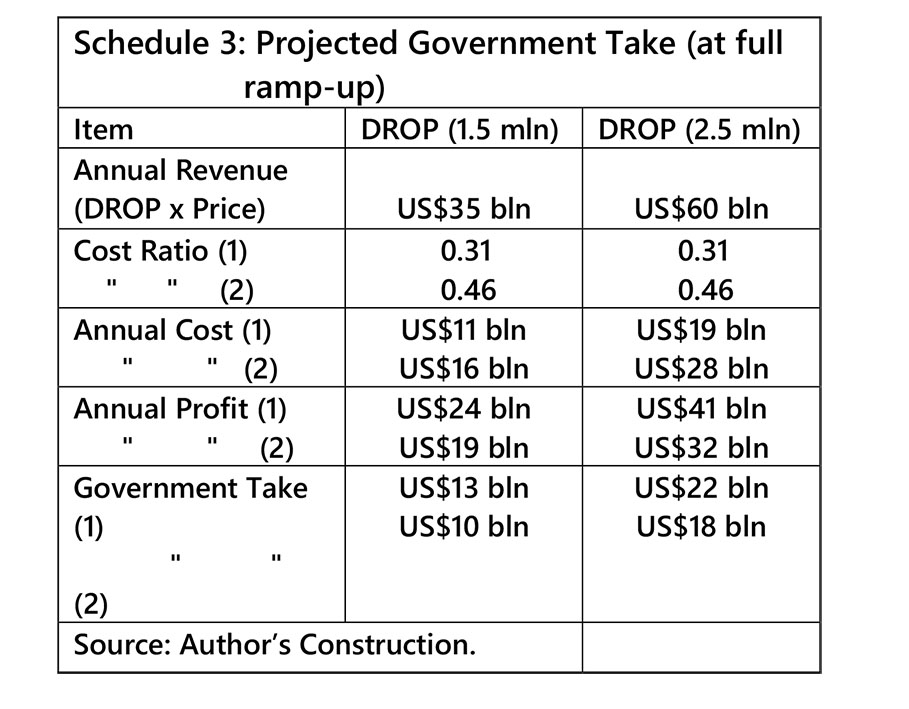

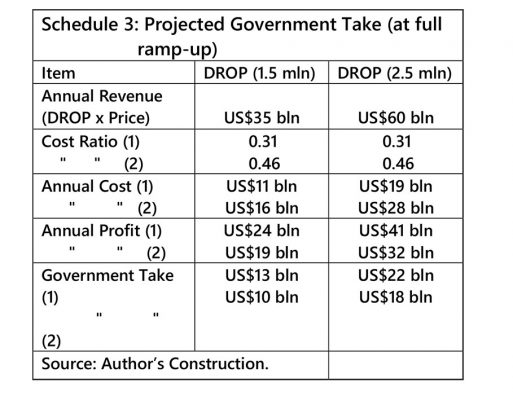

Adjusting for these differences and holding Rystad Energy’s assumptions constant, yield my ballpark estimates (as shown in Schedule 3). From general inspection, it is readily apparent that the major difference lies in the projected DROP. My range is 2.5 to 4.2 larger. This reflects my “bullish outlook” on Guyana’s emerging petroleum sector!

Adjusting for these differences and holding Rystad Energy’s assumptions constant, yield my ballpark estimates (as shown in Schedule 3). From general inspection, it is readily apparent that the major difference lies in the projected DROP. My range is 2.5 to 4.2 larger. This reflects my “bullish outlook” on Guyana’s emerging petroleum sector!

My values and Rystad Energy’s Analytics, therefore, yield Schedule 3.

Because Government Take represents Guyana’s petroleum sector revenues, locating this concept in a broader appreciation of Guyana’s political economy is imperative. While having to confront the challenges of developing its petroleum sector, Guyana is distinguished by weak capital-raising capacity; low technical and technological capacity; limited managerial capability; and, overall, woefully inadequate institutional and governance structures. It cannot therefore, confidently overcome certain petroleum industry challenges. One of these is the PSA provides for cost recovery, which in turn incentivises international oil company (IOC) contractors to “gold plate” their costs, in the face of such weak country capability.

All PSAs reflect the shifting balance of power between the contracting Parties (governments and international oil companies (IOCs)). Gold plating costs and similar complaints against PSAs have led to their continual re-assessment and re-negotiation! The difficulty remains, however, of finding a balance that retains their beneficial elements while reducing “gold plating.” Guyana, therefore, needs to be more rational in the evaluation of its present PSA. No PSA is perfect, but four considerations universally apply.

First, contracting parties to PSAs invariably differ in objectives, aims, and goals. Empirically, PSAs incentivise exploration and development (E&D) firms to pursue immediate profit and defer riskier fields. This has happened even in circumstances where riskier fields over the long run, have generated greater profit! Petroleum risk-reward theorems, reveal: the greater the risk, the more is the expected immediate profit required to incentivise E&P investors.

Second because PSAs allow claims for specified accrued costs incurred in E&D, they dis-incentivise efforts at cost reduction. The reason is cost efficiency gains are shared with government, in keeping with the pre-agreed profit-oil split. Logic suggests that, if IOCs are unable to benefit fully from their efforts to secure cost efficiencies, they may be dis-incentivised, when compared to situations that allow full benefit.

Third, PSAs can create opportunities for IOCs to obtain “windfall profits”. This occurs if, after the contract is signed, crude oil prices rise greatly above historical norms.

And, finally, evidence abounds that gold- plating costs is widespread practice among IOCs. This is a moral hazard indicating an almost systemic lack of good faith by parties to PSAs It derives from information failure that is mostly due to asymmetric information flows.

Contracts as Unique Instruments

Here I repeat my earlier contention that, worldwide, each and every PSA is unique, bearing their individual fingerprints. This happens despite PSAs being considered as one of four classes of petroleum contracts. Guyana’s PSA and Government Take therefrom need to be evaluated as a unique construction. One that recognises the whole PSA is more than a simple sum of its parts.

As Marten et al, 2015, notes, Government Take is a cost to IOCs. It therefore “defines a country’s competitiveness for internationally mobile E&D capital and it shapes global oil prices”. That article also notes globally, between 2009 and 2014 Government Take averaged 52 percent!

This means that the overall impact of a PSA (as captured in Government Take) is measured by the extent to which it simultaneously incentivises and dis-incentivises the contracting Parties, who have different goals and objectives. For this reason the ABC of energy economics posits that comparing the presence or absence of a particular fiscal levy or indeed comparing fiscal levies by their size is stupid and meaningless; unless the aim in doing this is to deceive the uninformed. Every rational person knows the absence of a fiscal levy is a profit incentive. Every reasonable government also knows it has to balance always this double-sided impact of all taxes.

I have already dealt with this issue repeatedly in this series and shall not repeat here.

Conclusion

Next week I wrap up discussion of my ballpark estimates and commence consideration of Guidepost 2 (spending of petroleum revenues).