Guyanese artist Frank Bowling is centre-stage right now at London’s Tate Britain gallery. Trinidadian Horace Ove is at Somerset House. Notting Hill Carnival is in a couple of weeks – 60 years on from its first launch.

Conversations in Arabic, French, Chinese, Somali buzz on London street corners. It’s hard to square this cosmopolitan vitality with the inward-looking Brexit politicians striving to create a “hostile environment” for the long-established Caribbean Windrush generation and more recent arrivals.

If you want to see what life was like for the Windrush people, check Andrea Levy’s “Small Island,” now playing to sold-out houses at the National Theatre.

Let’s start with Bowling. The Tate’s space is filled with huge, powerful strongly coloured abstract-expressionist canvases, some maybe 20-foot across. They are textured with acrylic paint, acrylic gel and foam, some mixed in jam jars, some splashed, poured, stencilled, splattered, some pasted on with decorators’ brushes and plasterers’ scrapers, and shaped in part by controlled accidents. Lighters, car keys, scraps or clothing are buried in there with the paint.

At 85, Bowling is now troubled by back pain and diabetes. For some recent work, he “paints” with a laser pointer, directing his grandson Frederik where and how to pour.

He was born in Bartica, where the wide Essequibo River meets the Cuyuni and Mazaruni. He grew up in New Amsterdam, above his mother’s Bowlings Variety Store: “she was a dress maker, a hat maker, maker of everything … she had magic fingers.”

In his teens, he left for London. He zigzagged into painting after national service in the RAF, and graduated from the Royal College of Art with a silver medal, in the same year David Hockney took gold. That came after a strange episode, where he was expelled for one term after marrying a staff member. Ah, the 1960s – it wasn’t all Swinging London.

Bowling was sometimes irritated by being pigeonholed as a “black artist” – though he once wrote: “All I know is I want to paint my people: that is, black people.” He found success in New York, where he still has a Brooklyn loft studio.

The Guardian in London quotes him on Derek Walcott, who “berated me for betraying the Caribbean spirit; if you weren’t painting cane-cutters and suffering, you weren’t a Caribbean artist.”

But his work links strongly to Guyana. Early pieces show his mother’s New Amsterdam shop. Map paintings build around outlines of Guyana and South America.

But more than this, there’s the light. Going home in 1989, he wrote: “I understood the light in my pictures … I saw a crystalline haze, maybe an East wind and water rising up into the sky … the light is about Guyana.”

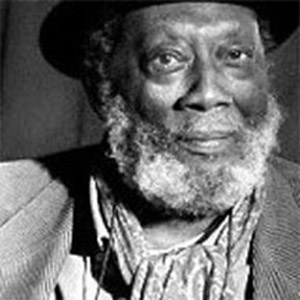

Horace Ové’s exhibition, curated by his son Zak, is very different. Branching out from Horace’s work as photographer and film maker, it bounces through decades of multicultural encounters with painters, writers, the whole mix-up world. The opening pulled a crowd of perhaps three thousand.

We see the 1950s Windrush generation of transplanted London Trinis – “The Lime” photographs Samuel Selvon, John La Rose and Andrew Salkey in winter clothes, behind them a brick-fronted terrace house.

We see a 1973 fashion shoot in Brixton Market – yellow and blue, hats and flared pants. The two confident models must now be 70-ish grannies.

The reach is wide, and the links sometimes personal – there is Walter Rodney, Embah, James Baldwin, Caryl Phillips, Toots and the Maytals, Minshall’s River from 1983 Carnival.

There’s a tree-top figure and landscape painted by Che Lovelace, half-echoing Cazabon’s View of Port of Spain from Laventille Hill. There are fast-work film posters by Peter Doig for showings at the Studio Film Club – Smile Orange, Black Orpheus, Pure Chutney.

Sadly, Horace Ové is now deeply troubled by Alzheimers. Sadly too, He was part of a generation that did not get the recognition they deserved – Zak had to pull work from dusty corners and under beds.

So, two big London events for Caribbean-origin artists. Why don’t we get these shows in Port of Spain?

The only time I’ve seen any of Peter Doig’s work here in a formal setting, was at the small Soft Box gallery on Alcazar Street, where it generously headlined a show with rising local artists. TT’s private galleries often work effectively and creatively – but neither they, nor any state-owned institution has resources for a big international event.

Exhibitions need cash. They need space with security and climate-control, insurance cover, funds for transport.

Curating a major show is a huge team effort, requiring creative, administrative and technical expertise. Some of the skills are here, but putting together a full package is another story.

There’s no high-quality permanent display of the creativity feeding TT’s Carnival.

We talk diversification. Visual arts and design can be part of that story. At the high end, Peter Doig’s work achieves sales figures in the millions. Plenty of mid-sized cities have fostered museums as tourism magnets.

TT’s gas boom is no longer fizzing. But Guyana’s oil cash starts to flow in a couple of months. Time, maybe, for energy company sponsorship to launch a world-beating visual and creative arts centre.

And yes, Carifesta coming next month.