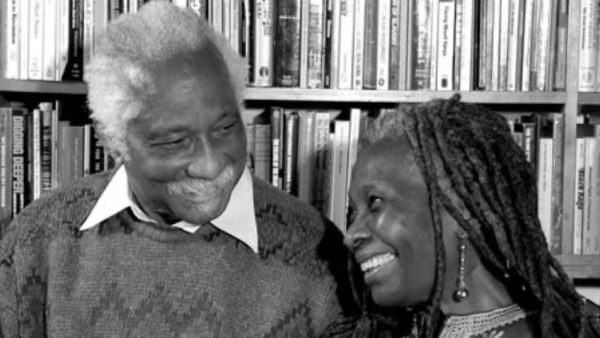

Having a conversation with Eric Huntley, who is just a month shy of his 90th birth anniversary, is like talking to a virtual history book. His life has been very rich in experiences, including the contributions that he and his late wife made to the civil rights struggles in both Guyana and England and their creation one of the latter’s first black-owned independent publishing houses.

Whether he is talking about how he helped to found the People’s Progressive Party (PPP), being sentenced to a year in jail after he refused to obey an order to remain within the confines of Soesdyke, which eventually led to him becoming unemployed, or about turning the front of his home into a publishing house, Huntley manages to offer the narrative in a manner that commands attention.

Huntley, who grew up in Kitty, left Guyana over 60 years ago after being forced into unemployment. He was recently in the country and he made a presentation at Moray House that was also intended for a now-postponed diaspora event organised by the University of Guyana. He also launched a publication, “Gems of Diaspora,” which traces a connection with Walter Rodney, among other things and a film on the subject is also in the making.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the birth of Bogle-L’Ouverture Publications (BLP), which published a collection of Rodney’s speeches and lectures, “The Groundings With My Brothers,” as its first title in 1969. Huntley and his late wife, Jessica, who died in 2013, named the company after two Caribbean liberation fighters, Paul Bogle, of Jamaica, and Toussaint L’Ouverture, of Haiti. “It was to pay homage to the contribution of the two stalwarts,” Huntley said during a recent interview with Stabroek Weekend.

In their own way, Huntley and his wife became stalwarts, having been cultural activists for over 60 years while in England. Their story, however, began in Guyana, on Brickdam to be exact, where they met while she was on her way home from typing classes. “I can remember it very well, you don’t forget those things,” he said.

According to him, they met in “typical Guyanese fashion.” Jessica was “minding her own business” on her way home from typing and shorthand classes and like men those days, “you meet a young lady in the streets and you say, ‘Hi girl, what’s your name.’” He added that it was very simple. They were married about two years later.

“And she never went back after that,” he shared, referring to the typing and shorthand classes. “I was not a very positive effect on her where the academic side was concerned,” he added and when asked why, he smiled and said, “You are asking the wrong person and she is not around…”

However, his positive influences on her included the activism they engaged in while in Guyana, where they were both founding members of the PPP. Jessica Huntley was also instrumental in starting the Women’s Progressive Organisation (WPO), which is the women’s arm of the party. However, even before they departed the country, Huntley said, he had no connection with the PPP.

Changed political situation

According to Huntley, it was because of the changed political situation that he was forced to leave Guyana. It was 1953. The then united PPP had won the election and everyone felt hopeful about the future, he said, but then the British government suspended the Constitution and so “politically the future looked very dim and… I was dismissed from the post office. I was restricted to Soesdyke and I broke the restriction order, so I was sentenced to a year in prison… at that time I was unemployed…”

The two options were leaving Guyana or entering the mining industry and he did not think he had what was physically needed for the latter. Huntley said he was fairly well prepared for England. In school, he had been taught British history, so he had an idea of what he was getting into and there were others who lived in England who assisted him, including lending him a British Air Force uniform to help him keep warm. He had taken his wedding suit—he said it was the best suit he had—to assist in this aspect but it could not withstand the weather.

He also had someone who gave him initial accommodation and looking back, he said, compared to others, his journey to England was “very fortunate” as he had a “good start.” He initially worked at the railway station and then the post office, where he spent about 10 years. “So, it was funny how the post office here dismissed me, and I got a post office job in England,” he said, while adding that at the time he worked at the largest post office in the world.

One year after his move to England, his wife left to represent the PPP at a women’s conference in Austria and never returned to Guyana as she joined her husband in England.

Very concerned

The birth of the publishing house, according to Huntley, was in response to the banning of Rodney from Jamaica in 1968. At the time, Rodney taught at the University of the West Indies’ Mona Campus and he had been seeking to raise the political and cultural awareness of the island’s working people, which led to the sanction. Many Jamaicans had protested the ban and in London a group of concerned West Indians, including the Huntleys, decided to challenge it by publishing and distributing Rodney’s speeches and lectures.

They had known Rodney before he went to Jamaica, Huntley said, and were very concerned about the 1968 ban, which he described a sort of “historical moment at the time, at least in the Caribbean.” When he and his wife met with others, they decided that protesting on the streets was not enough and they wanted to do something more permanent; it was during those discussions that the idea of the publishing house emerged.

At the time there were hardly any books about the history and culture of the Caribbean and Huntley said they felt, “if we didn’t do it, nobody [would] do it.” Three publishing houses emerged, which he said was very symbolic in what were “very revolutionary, very progressive times, very hopeful times.” The two other publishing houses were Allison & Busby and New Beacon Books and along with BLP, they all focused mainly on the Caribbean initially but eventually published across the board.

“[At the time] there were no outlets… there were a lot of writing taking place but no outlets for expressing in print…,” he said, while noting that even painters and sculptors could not have exhibitions.

Even though he recalled it being challenging managing the publishing house, as firstly they had to raise the money to publish, he noted, “Once you start out on a road with a vision or an idea, things just seem to fall into place.”

A poster made from a photograph of a Rastafarian published in a newspaper was sold and brought in some money. At the time, black people were not accustomed to seeing images of themselves in print, much less a Rastafarian, and because of this the poster was sold.

Jessica was against them asking “white people for money” for the publishing, which was the suggestion of some of the others in the committee. She instead contacted a friend of hers—Robert Hart—and he donated £100, which was a lot of money in those days.

Initially, they operated out of their home but following a complaint from someone in the neighbourhood they were forced to rent an office, and this meant overhead costs which they could ill-afford. But with determination they continued, and the publishing house made a significant contribution in the area; they even printed greeting cards with black people on them. However, he said, while publishing came easy, marketing, distribution and sales remained a challenge even though initially none of the authors received or expected to make royalties as they were just happy to get their work published. Although they had to make a profit, the publishing house was never set up to be a commercial enterprise but rather to contribute to black history. At the time, Huntley worked as an insurance agent.

The publishing house operated for about 18 years and Huntley recalled that its closure was triggered by new policies introduced by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s government. Those policies stopped the councils from buying books, educational grants were cut, and rents and taxes went up. The overheads made it impossible to continue publishing.

“The whole atmosphere changed after Thatcher came in,” he said of that time.

They went back to their house, where they published on a small scale and he said even today he does some publications. “Don’t ask me what will happen in the future,” he said laughing.

Lots of changes

On his many trips back to Guyana, Huntley said, he has observed lots of changes “some good, some bad, like everything else.”

For him one of the major issues is the lack of maintenance of the drainage system. “The system which we inherited from the Dutch has gone into disrepair… and Georgetown floods and stinks, which is a shame. It used to be a garden city; Georgetown used to be a garden city,” he said, shaking his head sadly. He was, however, pleased with how Kitty fared over the decades he has been away.

Returning to his wife, Huntley said she died after they had shared more than 60 years of marriage; she was his wife, comrade, mate, sister and companion for a very long time.

Their union produced three children, Karl Marx, Chauncey and Accabre. Karl died exactly 2 years before his mother’s October 23, 2013 death, on the very day.