“The Dark of the Sea” stays true to its name and opens in darkness and near the sea. A 15-year-old boy stands as the lone being between the darkness and the waves. The reader is not quite sure what is happening as we are flung into the middle of the boy’s attempt to right some wrong. Before we can figure it out, though, we are thrust back into the past, where our story begins.

The brief prologue, especially when measured against the proper opening of the story a few pages later, seems to evoke an undercurrent of wish fulfilment. Danesh, our young hero, appears to be an unlikely hero. He is, after all, a mere high-school boy, struggling to make it through secondary school. But where better than a fantasy story to turn the unlikeliest of persons into heroic figures?

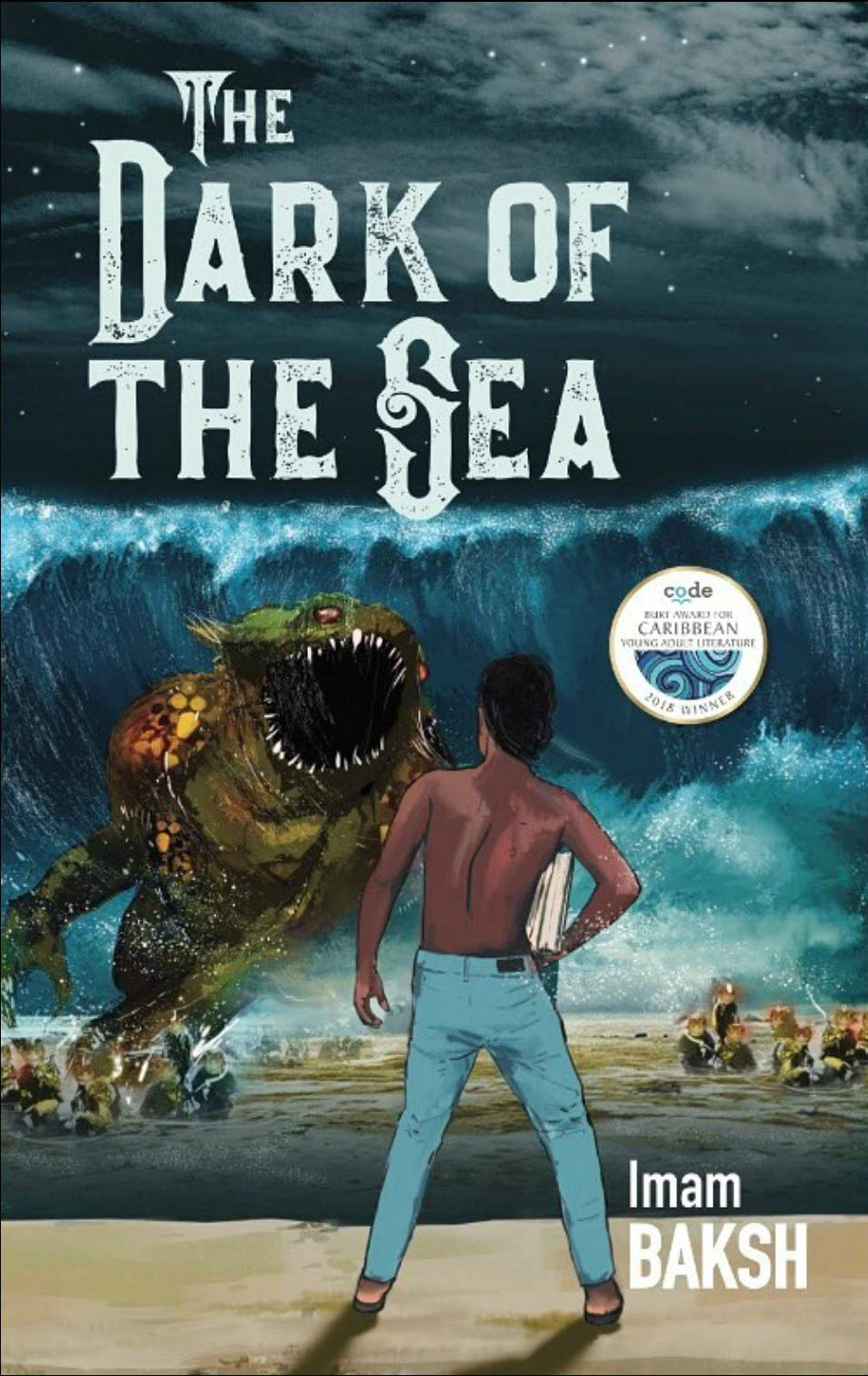

It’s clear from his prose that Guyanese writer Imam Baksh approaches the fantasy genre with great love and knowledge for the lineage of writers that have come before him. His new young-adult book fantasy, which was awarded the Burt Award for Caribbean Young Adult Literature in 2018, blends the well-worn tropes of the genre, with a specific and deliberate Guyanese awareness, localising the fantasy worlds of literature in ways that are immediately noticeable.

Early in the novel, Danesh gazes out at Georgetown. He and his best friend, Amit, are trying to see the fireworks for the Independence Day celebrations in Essequibo, where the novel is set. Baksh’s concern and empathy for the lives of these rural people, existing on the edges of the mainstream, is a major thematic thread in “The Darkness of the Sea”. It’s there in the suffocation Danesh and his colleagues feel in school, in Amit’s decision to drop out at 15 to find a job, and in the hazy listlessness that seems to envelope the lives of those waiting for a way out. Enter trouble from underwater.

Baksh holds the novel’s supernatural inclinations close to his chest until the Danesh’s first encounter with a farmaid, a sea-creature, 30 pages into the near 200-page novel. But, the occurrence, like many of the developments in “The Dark of the Sea,” centre on things hiding in plain sight, ignored rather than invisible. Danesh, for example, is marked as illiterate at school, struggling with teachers who seem unwilling to grapple with what is dyslexia more than ignorance. Later in the book, when two big twists arrive, they resonate not because of their surprise but more because of the way Baksh has been laying the groundwork for these imminent developments throughout. The moral of the story could very well be, “Don’t ignore what’s right in front of you.”

It’s why the vague strains of wish-fulfilment in Danesh’s chosen-one lineage feel apt in the novel. The novel moves between the underwater world he discovers and the above-the-ground crisis that threatens to upend his life. The two worlds will meet near the end, but for the most part the novel is split in two between them. The fact that the underwater dreamscape often feels less impactful than you would expect for a fantasy novel, though, makes sense as the story develops. It’s not so much that Baksh’s world-building underwater isn’t in earnest, but more that the above-ground dilemmas–a school friend’s flirtation with a young teacher, Amit’s pining for a girl who will soon be betrothed to a foreigner, and his rapscallion like aji who seems too disreputable for his own good–resound with a note of empathy that makes these moments immediately familiar to Guyanese readers. Baksh is thoughtful in his deployment of the familiar themes of the region–the teenage suicide rate, the restless hopelessness of the less academically inclined, even the country’s English/Creole divergence is given voice in a humorous conversation underwater.

And it is that keen sense of representation that runs throughout the text. Even when the advanced language of the prose sometimes seems to conflict with the simplicity of the dyslexic Danesh, the ideas in “The Dark of the Sea” feel familiar and earnest enough to keep the pages turning. The twist that comes thirty pages before the end is not great in the way of surprise but benefits from the way it’s woven into the fabric before. Baksh is generous with his narrative so that every incidental character and moment that surfaces in the early sections acquits itself as something of value by the end. It’s all back to that theme–pay attention to what’s in front of you because everything has some purpose. This idea pays off in numerous ways throughout the book.

When the novel ends with a brief melancholic epilogue to match the brevity of its prologue, it is perhaps exactly what you would expect from this kind of story. Despite the brief time covered, Baksh’s intentions of turning this adventure story into a coming of age tale of sorts are clear. And, in this way, when the adventures come to a close at the end, we realise it’s not really about the adventures of the sea, no matter what the title says. Instead, Baksh’s concern is more existentialist and humane. It’s a welcome recognition of those universal themes dressed up in Guyanese clothes.