DHAKA, (Thomson Reuters Foundation) – As countries around the world try to cut down on throw-away plastic shopping bags, Bangladesh is hoping to cash in on an alternative: plastic-like bags made from jute, the plant fibre used to produce burlap bags.

Bangladesh is the world’s second biggest producer of jute after India, though the so-called “golden fibre” – named for its colour and its once-high price – has lost its sheen as demand has fallen.

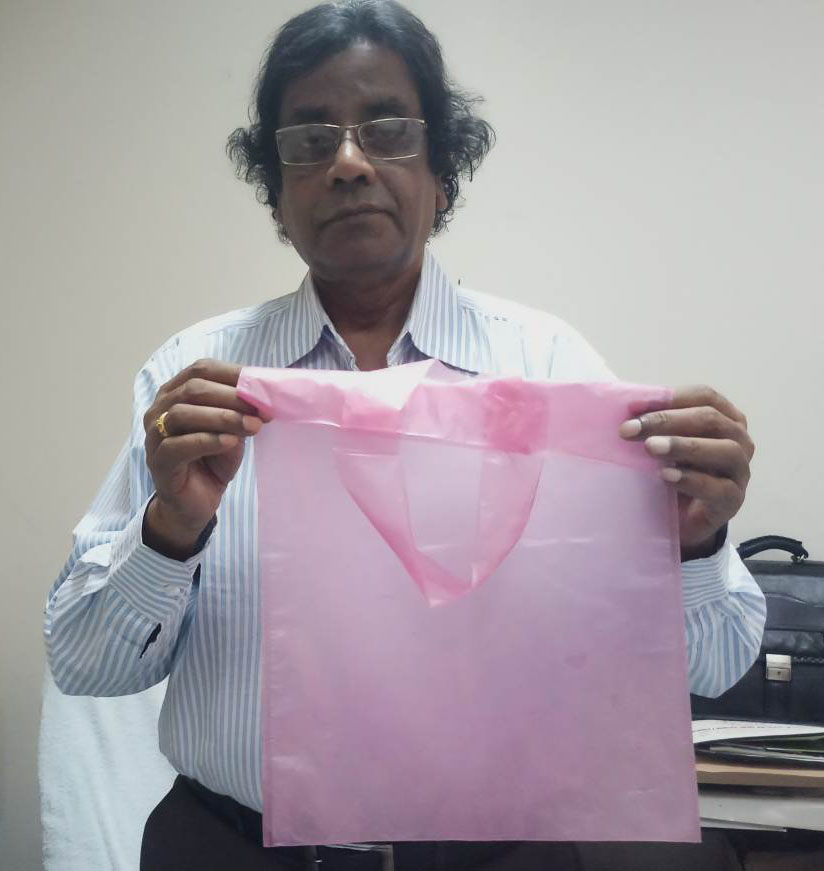

Now, however, a Bangladeshi scientist has found a way to turn the fibre into low-cost biodegradable cellulose sheets that can be made into greener throw-away bags that look and feel much like plastic ones.

“The physical properties are quite similar,” said Mubarak Ahmad Khan, a scientific adviser to the state-run Bangladesh Jute Mills Corporation (BJMC) and leader of the team that developed the new ‘sonali’ – the Bengali word for golden – bags.

He said the sacks are biodegradable after three months buried in soil, and can also be recycled.

Bangladesh is now producing 2,000 of the bags a day on an experimental basis, but plans to scale up commercial production after signing an agreement last October with the British arm of a Japanese green packaging firm.

Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina in March urged those working on the project “to help expedite the wider usage of the golden bags” for both economic and environmental gains.

In April, the government approved about $900,000 in funding from Bangladesh’s own climate change trust fund to help pave the way for large-scale production of the bags.

“Once the project is in full swing, we hope to be able to produce the sonali bag commercially within six months,” Mamnur Rashid, the general manager of the BJMC, told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

BIG DEMAND

Bangladesh was one of the first countries to ban the use of plastic and polythene bags, in 2002, in an effort to stop them collecting in waterways and on land – though the ban has had little success.

Today more than 60 countries – from China to France – have outlawed the bags in at least some regions or cities, Khan said.

As the bans widen, more than 100 Bangladeshi and international firms are looking into using the new jute-based shopping sacks, Khan said.

“Every day I am receiving emails or phone calls from buyers from different countries,” he said, including Britain, Australia, the United States, Canada, Mexico, Japan and France.

The bag is likely to have “huge demand around the world,” said Sabuj Hossain, director of Dhaka-based export firm Eco Bangla Jute Limited.

He said his company hopes eventually to export 10 million of the bags each month.

Commercial production is expected to start near the end of the year, said Rashid of the BJMC.

Khan said that if all the jute produced in Bangladesh went to make the sacks, the country was still likely to be able to meet just a third of expected demand.

While Bangladesh’s own plastic bag ban is now almost two decades old, million of the bags are still used each year in the South Asian country because of a lack of available alternatives and limited enforcement, officials said.

About 410 million polythene bags are used in the capital Dhaka each month, the government estimates, and in some waterways such as the Buriganga River a three-metre-deep layer of discarded bags has built up.

The new bags should help ease the problem, said Quazi Sarwar Imtiaz Hashmi, a former deputy director general of the Department of Environment.

“As jute polymer bags are totally biodegradable and decomposable, it will help check pollution,” he said.