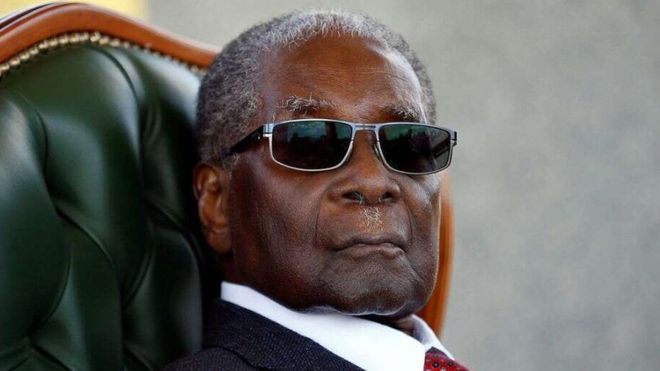

HARARE, (Reuters) – Robert Mugabe, the bush war guerrilla who led Zimbabwe to independence and crushed his foes during nearly four decades of rule as his country descended into poverty, hyperinflation and unrest, died yesterday. He was 95.

Declared a national hero within hours of his death by the long-serving aide who succeeded him as president, Mugabe was one of the most polarising figures in his continent’s history – a giant of African liberation whose regime finally ended in ignominy when he was overthrown by his own army.

He died in Singapore, where he had long received medical treatment.

Granting him the status of national hero in a televised address, President Emmerson Mnangagwa praised Mugabe an icon and a “remarkable statesman of our century.”

“On the backdrop and solid foundation of the first republic which he moulded as its leader, we today recover and grow,” he said.

Mnangagwa, Mugabe’s one-time security chief who helped oust him from power, had returned home earlier in the day after cutting short a trip to a World Economic Forum summit in South Africa.

Tributes poured in from African leaders. South Africa’s government mourned a “fearless pan-Africanist liberation fighter”. Kenya’s President Uhuru Kenyatta hailed a “man of courage who was never afraid to fight for what he believed in, even when it was not popular”.

At home, even foes paid respects.

“He was a colossus on the Zimbabwean stage and his enduring positive legacy will be his role in ending white minority rule & expanding a quality education to all Zimbabweans,” tweeted David Coltart, an opposition senator and rights lawyer.

Others said his legacy was overshadowed by the harm he did to his people.

“We of course express our condolences to those who mourn, but know that for many he was a barrier to a better future,” said a spokeswoman for Boris Johnson, prime minister of former colonial power Britain. “Under his rule the people of Zimbabwe suffered greatly as he impoverished their country and sanctioned the use of violence against them.”

On the streets, the response was mostly more generous.

“He was iconic, he was an African legend. His only mistake was that he overstayed in power,” said Harare resident Onwell Samukanya. Another, Sellina Mugadza, said: “Of course we know that you cannot do good to everyone, but to me he was good.”

RECONCILIATION AND DEATH SQUADS

Mugabe was feted as a champion of racial reconciliation when he first came to power in 1980 in one of the last African states to throw off white colonial rule. By the time he was toppled to wild celebrations across the country of 13 million, he was viewed by many at home and abroad as a power-obsessed autocrat who unleashed death squads, rigged elections and ruined the economy to keep control. Mugabe called his departure an “unconstitutional and humiliating” betrayal. Confined to his sprawling Harare mansion, he stayed bitter to the end.

Mugabe took power after seven years of a liberation war, with a reputation as “the thinking man’s guerrilla”. He held seven degrees, three earned behind bars as a political prisoner of then-Rhodesia’s white minority rulers. Later, he would boast of another qualification: “a degree in violence”.

Just three years after independence, he sent the army’s North Korean-trained Fifth Brigade into the homeland of the Ndebele people to crush loyalists of his rival, Joshua Nkomo.

Human rights groups estimate as many as 20,000 people died in a two-year purge the opposition referred to as genocide.

Villages were destroyed wholesale, according to “Breaking the Silence”, a 1997 report by the Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace, with some victims forced to dig their own graves.

Many years later, he acknowledged the episode was “very bad” and blamed it on renegade soldiers. Researchers say the evidence shows he knew what was happening all along.

ECONOMIC CRISIS

In fiery speeches throughout his rule he painted his actions as a just response to a racist colonial legacy, with his most important priority the redistribution of land held by whites.

When he failed to change the constitution to allow seizure without compensation, his followers stormed farms. His enemies called it a lawless grab for power and wealth. Output cratered and southern Africa’s breadbasket could barely feed itself.

GDP fell by 40% and inflation reached 500 billion percent; he blamed a Western conspiracy.

As his health declined, his foes suspected a plan to pass control to a much younger wife they called “Gucci Grace” for her lavish lifestyle.

“It’s the end of a very painful and sad chapter in the history of a young nation, in which a dictator, as he became old, surrendered his court to a gang of thieves around his wife,” Chris Mutsvangwa, leader of Zimbabwe’s influential liberation war veterans, told Reuters after Mugabe’s removal.

Born on Feb. 21, 1924, on a Roman Catholic mission near Harare, Mugabe was educated by Jesuit priests and worked as a primary school teacher before going to South Africa’s University of Fort Hare, then a breeding ground for African nationalism.

Returning to then-Rhodesia in 1960, he entered politics and was jailed for a decade for opposing white rule. After his release, he rose to lead the Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army guerrilla movement.

“You have inherited a jewel in Africa. Don’t tarnish it,” Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere told him during the independence celebrations in Harare.

Just under two years after his departure, Zimbabwe has yet to recover its lustre.

Beset by triple-digit inflation, rolling power cuts and shortages of basic goods, the economy is mired in its worst crisis in a decade, while political opponents say a clampdown on dissent by Mnangagwa’s government has revived memories of the Mugabe era.