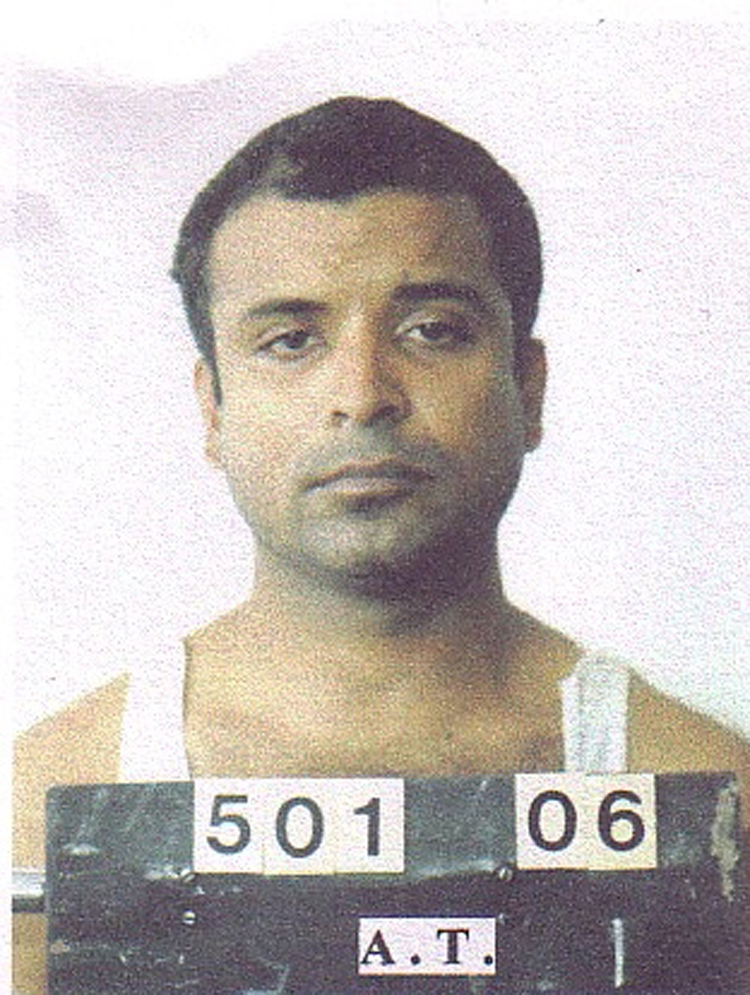

There can be few people whose return to this country generates as much public interest as that of Roger Khan. But then again, there are few criminals who have had as much influence – albeit indirect – on the structures of the State as Roger Khan. Last week, it was announced that although he had been released from jail in the United States following time served on a drug-trafficking conviction, and was due to be deported on Thursday, his return had been postponed. No indication was given as to how long this delay might last.

Certainly, if this most infamous of drug lords came now, he would be arriving in the middle of another of our interminable political impasses, and it seems reasonable to hypothesise that at least on the face of it, the government might be more receptive to his reappearance here than would the opposition. Even in his absence, Roger Khan’s name surfaced with regularity on the coalition’s hustings during the last election campaign, particularly in relation to allegations about his association with the administration of Mr Bharrat Jagdeo.

Yet for all of that, after four years in office this government has made no attempt to go after his assets here, and it is not at all clear that they would do so even after he touched down at Timehri. In any event, they have certainly made no unambiguous statement to that effect. Considering that he received his sentence more than a decade ago, one imagines that it would hardly be a straightforward matter following the trail of his illegal gains now, more particularly in a place like Guyana.

Then there is the matter of an inquiry into the numerous killings locally that could be laid at Khan’s door either directly, or which occurred at his instigation, and which in January last year, then Minister Joseph Harmon appeared to suggest was imminent. “They [the killings] range over a period of time but we cannot of course do one inquiry to cover all of them at the same time so we may very well be dealing with individual issues as we go along. So during the course of this week, by the end of this week, we will launch an inquiry into one period of the killings …” he was quoted as saying. When he was asked which period would be focused on first, he responded that that information would be made public when the Commission of Inquiry was launched. “You will get either the period or the particular issue which is going to be dealt with,” he said.

His comments came in the wake of an address by President David Granger to members of the GDF at the opening of their annual conference. He told them that a Commission of Inquiry was under consideration, and that his administration would ensure that the perpetrators of the killings were brought to justice. Nothing much more has been heard about it since.

It is one thing, of course, to reiterate the accusations about Roger Khan’s links to a previous administration, and his alleged connections to one-time Minister of Health Dr Leslie Ramsammy and the late former Home Affairs Minister Ronald Gajraj when the prime witness is locked up abroad, and quite another to hold a Commission of Inquiry where that witness could give live testimony. The period of interest began in 2002, when a prison escape by five inmates led to the greatest level of criminal violence in this country’s modern history, and for four years thereafter, it is believed that the government exercised no restraint on Roger Khan where the killing of those he deemed criminals was concerned. His death squad(s) were graphically dubbed the “Phantom Squad” by Dr Roger Luncheon.

Dr Ramsammy has vehemently denied any links to Roger Khan, although he has not yet provided satisfactory explanations for some of the evidence, more especially in relation to the importation of the spy equipment which was later seized from the drug trafficker. This evidence was given in court during the trial of Khan’s lawyer, Robert Simels, or surfaced shortly thereafter. There is, too, the material which emerged following the publication of the WikiLeaks cables, at least one item of which is not based on secondary information.

As for Mr Jagdeo, in 2015, he denied ever knowing Roger Khan; “[He] was never my friend,” he said.

It may be that the government decided last year that there was no point in holding a Commission of Inquiry into the murders if Roger Khan himself was not present, although to establish one when he returns would raise all kinds of difficulties. Since he is associated with so many killings and is a convicted drug trafficker, clearly a criminal investigation with a view to charging him is what would be required. A Commission of Inquiry would inevitably involve giving him some level of immunity, which, in his case, would be problematic if he hadn’t been charged first. Even if he is charged, one imagines he would insist on some kind of guarantee and concessions before he would co-operate. Of course, it may be that the present government would be so anxious to learn what Khan knows, that it would be prepared to do some kind of deal if he could be prevailed upon to talk.

That altogether apart, it is interesting that when Mr Harmon spoke of an inquiry, he raised the possibility of several based on periodicity or subject matter, rather than just one. This would seem a little odd, considering that this constitutes a cohesive span of time with a distinct character. Could it be that they were toying with the idea of limiting the scope of any formal inquiry?

Of course allegations have been made about links the criminals of the 2002 era had with elements in the then opposition, and it is for this reason that some in the past have called for a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, rather than a Commission of Inquiry. There is too, the matter of the role of the police and the army, the veracity of whose official reports on Buxton, Mr Jagdeo has impugned. “You had people, who were working from the inside to undermine the process [of liberating Buxton],” he has averred.

From the other side, Roger Khan himself took out an advertisement in certain newspapers in 2006 in which he claimed he had worked with the police during what was colloquially known as the crime spree. “During the crime spree in 2002,” he wrote, “I worked closely with the crime-fighting sections of the Guyana Police Force and provided them with assistance and information at my own expense. My participation was instrumental in curbing crime during this period.” This claim would certainly invite an investigation of the police during the period, something to which President Granger might conceivably be averse.

If Roger Khan is deported in the immediate future, he will land in the penumbra of an election, and both sides will no doubt try to mine whatever he has to say – if anything − for campaign material. Everyone else, criminal charges apart, has a simpler objective: the truth.