WASHINGTON (Reuters) – A new way of studying planets in other solar systems – by doing sort of an autopsy on planetary wreckage devoured by a type of star called a white dwarf – is showing that rocky worlds with geochemistry similar to Earth may be quite common in the cosmos.

In a study published on Thursday, researchers studied six white dwarfs whose strong gravitational pull had sucked in shredded remnants of planets and other rocky bodies that had been in orbit. This material, they found, was very much like that present in rocky planets such as Earth and Mars in our solar system.

Given that Earth harbors an abundance of life, the findings offer the latest tantalizing evidence that planets similarly capable of hosting life exist in large numbers beyond our solar system.

“The more we find commonalities between planets made in our solar system and those around other stars, the more the odds are enhanced that the Earth is not unusual,” said Edward Young, a geochemistry and cosmochemistry professor at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), who helped lead the study published in the journal Science. “The more Earth-like planets, the greater the odds for life as we understand it.”

The first planets beyond our solar system, called exoplanets, were spotted in the 1990s, but it has been tough for scientists to determine their composition. Studying white dwarfs offered a new avenue.

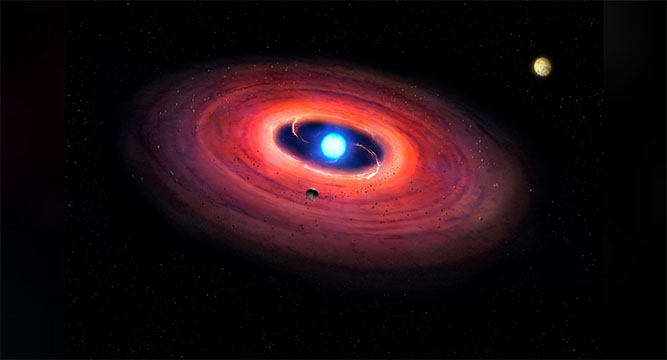

A white dwarf is the burned-out core of a sun-like star. In its death throes, the star blows off its outer layer and the rest collapses, forming an extremely dense and relatively small entity that represents one of the universe’s densest forms of matter, exceeded only by neutron stars and black holes.

Planets and other objects that once orbited it can be ejected into interstellar space. But if they stray near its immense gravitation field, they “will be shredded into dust, and that dust will begin to fall onto the star and sink out of sight,” said study lead author Alexandra Doyle, a UCLA graduate student in geochemistry and astrochemistry.

“This is where that ‘autopsy’ idea comes from,” Doyle added, noting that by observing the elements from the massacred planets and other objects inside the white dwarf scientists can understand their composition.

The researchers observed a fundamental characteristic of the rocks: their state of oxidation. The amount of oxygen present during the formation of these rocks was high – just as it was during the formation of our solar system’s rocky material. They focused on iron, which when oxidized ends up as rock.

“Rocks are rocks, even when they form around other stars,” Young said.

The closest of the six white dwarf stars is about 200 light-years from Earth. The farthest is about 665 light-years away.