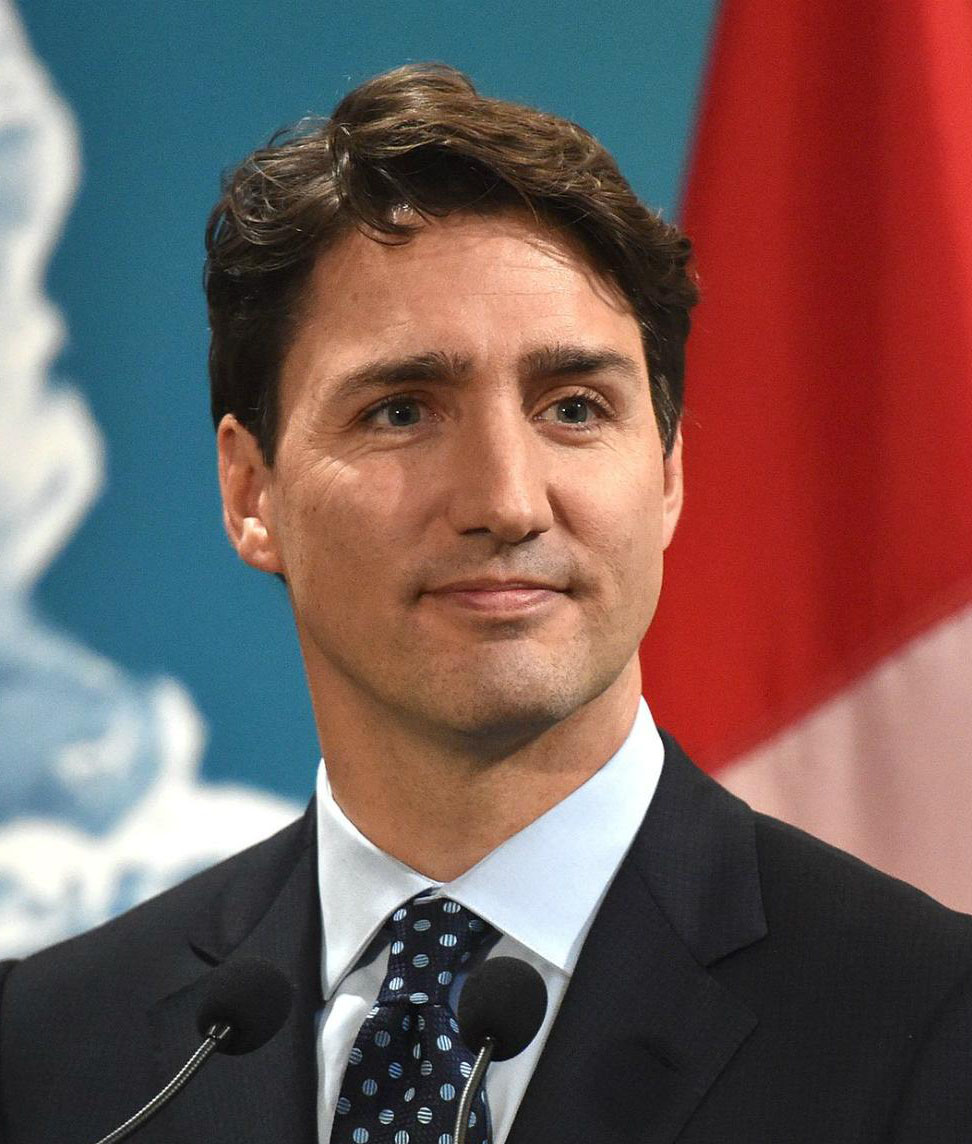

TORONTO, (Reuters) – Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau held on to his job in yesterday’s election, securing his spot as one of the world’s few high-profile progressive leaders, but tarnished by scandal and with his power diminished.

The man former U.S. President Barack Obama privately anointed as a successor in global diplomacy survived a blackface scandal and the disclosure that he sought to interfere with a federal corruption prosecution, but just barely.

Trudeau’s Liberals, who won power four years ago with a strong parliamentary majority, were projected by the Canadian Broadcasting Corp to form a minority government after a tight election battle with the Conservative Party led by Andrew Scheer. That would leave Trudeau needing the support of smaller opposition parties to govern.

“The hype was so great when he ran before, it would be hard to match that,” said Jonathan Rose, a political science professor at Queen’s University. “The burden of governing both wore him down and wore voters down.”

Alternately charming and awkward, the former teacher and snowboard instructor swept to power in 2015 at the age of 43. Born on Christmas Day in 1971 to a sitting Canadian prime minister, Pierre Trudeau, the younger Trudeau grew up in the spotlight.

On taking over as prime minister, Trudeau said he would tackle climate change, overhaul the electoral system, legalize marijuana and have Canada take in 25,000 Syrian refugees. He proclaimed himself a feminist, and unveiled a gender-balanced Cabinet. Mobbed for selfies, Trudeau brought style to an office that is usually dour, and broadcast much of it on social media.

But before long, key allies turned hard to the right – the UK voted to leave the European Union, and the United States elected Republican Donald Trump as president.

In time, Trudeau concentrated power in the prime minister’s office and abandoned electoral reform. His government bought the troubled Trans Mountain oil pipeline, infuriating environmentalists, even as it moved to put a price on carbon, alienating the energy industry.

The run-up to the campaign was marked by high-profile Cabinet defections, and a watchdog report that found Trudeau and his team tried to undermine a federal prosecutor’s decision to put construction firm SNC-Lavalin Group Inc on trial for corruption.

Then, as the campaign began, a 2001 photograph emerged that showed Trudeau, then 29, at a party, his face covered in dark makeup. More photographs of him in blackface quickly followed, as Trudeau apologized. The images, which briefly dented the Liberals’ popularity, ran counter to a carefully managed public persona.

Trudeau also promised “reconciliation” with Canada’s indigenous peoples, who make up about 5% of the country.

Ahead of Monday’s election, the indigenous political group Assembly of First Nations (AFN) said there had been “concrete action and investments” but “we have considerable ground to make up to ensure First Nations and Canadians share an equal quality of life.”

On the eve of the election, the race looked close. Trudeau had a shot at a dispiriting honor: the first prime minister since 1935 to lose power in the next election after winning a first-term majority.

“It was inevitable that some of that shine was going to come off, and I think we’ve seen that,” said Andrew MacDougall, who was spokesman for former Prime Minister Stephen Harper, whose Conservative government was ousted by Trudeau’s Liberals in 2015. “But he’s not that far away from where he was when he was elected.”

The friendship Trudeau forged with Obama in another era seems to endure. The two were spotted dining together in Ottawa earlier this year, and the former president tweeted his endorsement last Wednesday of Trudeau’s re-election.

In a recent book, former Obama adviser Ben Rhodes described a 2016 meeting between the two leaders.

“Justin, your voice is going to be needed more,” Obama said, according to Rhodes. “You’re going to have to speak out when certain values are threatened.”