Last week’s column briefly evaluated the perspective of private investors and their value added proposals for constructing “modular mini-refineries” utilising Guyana’s crude oil. Today’s column offers an evaluation of the Government’s “proposal” to construct a State-owned oil refinery similarly based on Guyana’s crude slate. My recommendation, expressed below, is: the latter makes no economic sense presently. Next week’s column will stipulate the decision rules to guide both public and private refinery proposals on offer.

Background

The problematic that I address today is: should the State establish a local refinery using Guyana’s crude? The prospective refinery size is about 100,000 barrels per day (BPD), functioning at a level of complexity/capability exceeding that found in typical modular mini-oil refineries. In 2017 Exxon’s Country Manager had indicated that a refinery of such size would be unprofitable! A much larger refinery was needed, in order to reap economies of scale at levels prevailing in the Western Hemisphere!

In the same year, the Ministry of Natural Resources (MoNR) authorised a feasibility study of a state-owned refinery. This task was undertaken by Pedro Haas, of Hartree Partners, who gave a PowerPoint presentation of the study on May 17, 2017. As indicated, his feasibility/cost benefit analysis was aimed at determining “the viability of the idea.” In other words, to establish whether the State should proceed or not.

The strategic question the Study therefore posed was: “Given Guyana’s demand for fuels, and its oil and gas production prospects, what are the economics of the State investing in domestic refining assets?” Indeed, this question is at the heart of every feasibility study. That is, whether to proceed or not.

Guyana’s imported petroleum products are: mogas, gasoil, kerosene, jet fuel, fuel oil, liquefied petroleum gases (LPG), and aviation gasoline. The annual demand for these is about 13 – 14 million barrels (MB), with recent rapid growth, rising from 11.6 MB in 2010.

Refinery Economics

The Haas’ Study identified the need for a “grassroots” refinery. That is, one built from scratch (including refinery infrastructure). It is also expected to be constructed “at one go”. The methodology utilised followed standard lines.

Thus, given expected prices, experts provided capital estimates, (construction costs and their timelines); operating costs and revenues were proxied from existing refinery margins, bearing in mind the estimated refinery configuration and what this predicts for capacity, capability and complexity, and therefore, the refined products produced.

Refinery Model Assumptions

Several assumptions were employed for estimating refinery viability. These include: 1) size: 100,000 barrels of oil per day; 2) the complexity level of fluid catalytic cracking. 3) A 10-year average margin of a 50/50 mix of a Louisiana heavy and light low sulphur oil in a typical US Gulf Coast refinery (US$5.84); 4) overall construction cost of US$5.2 billion; 5) cost of debt equivalent to the Bank of Guyana’s 364-day Treasury, plus a 0.5% premium; 6) a cost of 10%; 7) an exchange rate used of GY$206.5 to US$1; 8) operating costs for the refinery are proxied by the IEA’s refinery margin estimates, and given as US$3.30 per barrel of oil. And, finally, the timeline for construction of the refinery is 60 months, with the project life that normally applied in such studies ─ 30 years. Given the refinery capacity, on completion, it exports the refined products, which are not consumed locally.

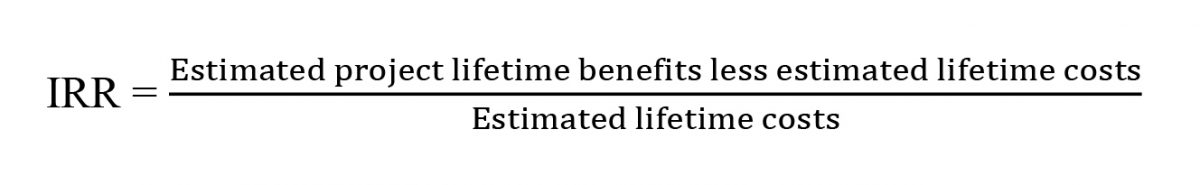

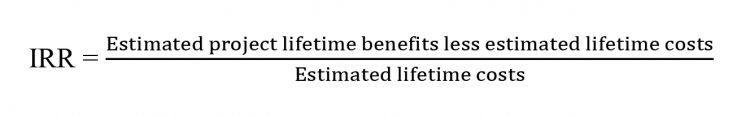

IRR

The Internal Rate of Return (IRR) of the oil refinery project is negative.

NPV

The Net Present Value (Present Value of All Benefits less Present Value of All Costs) was minus 3.04 billion US$ for the base case scenario. The Study refers to two other scenarios for basing this calculation; one of which obtains when the “location factor” for a Guyana grassroots refinery is calculated at 20% and its offsite construction factor is costed at a factor of 80%. Here the result is minus 2.44 billion US$. For the other scenario, the “location factor” is set at 40% and the grassroots effective construction factor is set at 120%. In this case the negative NPV rises to minus 3.69 billion US$.

Other Economic Considerations

In addition 1) the size of the country’s GDP is presently, about 4 billion USD; which is equal to 0.01 percent of global GDP. With construction costs at US$5 billion, this is more than current GDP. Gross national saving is about one-fifth of current GDP, which therefore, necessitates foreign borrowing to build the refinery. However, with a negative rate of internal return, along with the refinery losing half or more of the investment during the project life, this makes it highly unprofitable and unlikely that, investors would acquire debt in such a project, or indeed risk their equity.

2) The capital ratio is also quite high for a State whose current budget expenditures at basic prices and revenues are each approximately US$1 billion and revenues US$1 billion. Even with large anticipated oil revenues after 2020, Guyana, with its current needs, cannot afford a questionable venture requiring such relatively large capital expenditure so highly likely to go broke.

3) Most, if not all refineries, operate as price-takers for both their inputs and outputs. These features severely constrain their commercial flexibility.

4) All oil refineries are confronted with considerable risks and uncertainties; and, consequently a range of testing choices. Over the short-term: “refineries try to juggle the choices in their crude diet and its product slate”. But in the long run each must decide whether to invest in changing its configuration or shutting down! In making this crucial decision refinery size (and hence capacity to reap economies of scale) and refinery complexity determine the potential profitability of the refinery.

5) Further, the location of Guyana’s crude is offshore, below sea-level depth, and faces a global scarcity of relevant skills. These put immense pressure on deliverable costs to the refinery.

Conclusion

Given the above, it is clear there is no economic sense in constructing a state-owned refinery at this juncture. I therefore, offer next week the “decision rules” to govern the Government of Guyana’s refinery policy. This then wraps-up discussion of Guidepost 4 in Part 2 of Guyana’s Petroleum Road Map.