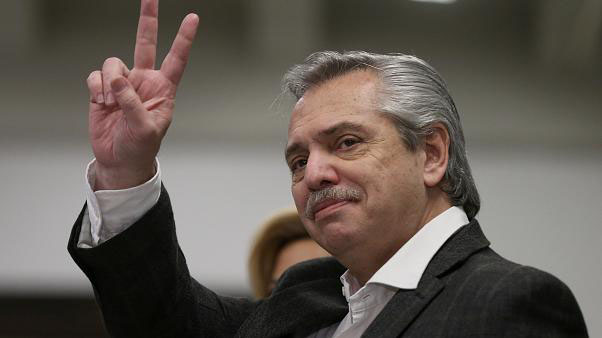

BUENOS AIRES, (Reuters) – Argentina’s president-elect Alberto Fernandez vowed yesterday to ‘turn the page’ on the IMF-backed policies of incumbent Mauricio Macri, after voters weary of rising poverty and inflation swept the left back to power in Latin America’ No.3 economy.

Argentina’s electorate voted overwhelmingly on Sunday to ditch the economic liberalization and austerity of conservative Macri, which has left the commodities-rich nation teetering on the brink of a $100 billion debt restructuring, and turned instead towards the Peronist left.

The two leaders held brief talks on Monday about a transition of power, with Fernandez vowing to take the country of over 44 million people in a vastly new direction to the business-friendly reform agenda espoused by his predecessor, a staid former magnate with close ties with the United States.

“We began to turn the page today. This page (of Macri) will be forgotten and we will start writing another story on December 10 when we arrive with Cristina in government,” Fernandez said after his election win, referring to his divisive running mate Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner.

The return of the Peronists, and populist ex-president Fernandez de Kirchner, has startled some in Argentina and beyond, concerned that reforms to open Argentina more to global markets could be undone.

Markets on Monday were mixed, still uncertain how to respond to the result with many questions unclear.

Argentina’s central bank moved swiftly in the early hours of Monday to tighten capital controls during the transition and the peso closed 0.65% stronger.

In the parallel black market, the local currency was more volatile, having fallen as low as 77 to the dollar, while Argentine over-the-counter bonds dipped 1.6% on average.

How Macri and Fernandez work together over the next few weeks will be key. With talks looming with creditors over $100 billion in debts, reserves are dwindling, inflation is sky-high and rising poverty is sparking anger.

“I’m worried because I already went through Cristina’s government and it was very hard for farmers,” said Sergio Storti, 58, a grains and cattle farmer in the bread basket province of Buenos Aires.

Markets are watching closely to see where Fernandez, a dark horse candidate who was a relative unknown until earlier this year, stands on key policies that could impact the peso, which crashed in August after he secured a landslide win in a primary vote.

In a bid to soothe markets, Fernandez and Macri signaled with their meeting on Monday that they would work together during the transition until the new government takes over in December.

Treasury Minister Hernan Lacunza told reporters the two leaders had shared a “good dialogue” and there would more meetings between the two teams in coming days.

“(There is) total willingness from this outgoing government to work together in the transition,” he said. Macri later said in a tweet that he and his team would be available to work with Fernandez to ensure a “democratic transition”.

Fernandez’s victory shifts the political balance in Latin America, with two of the region’s top three economies – Mexico and Argentina – now helmed by leftist leaders, even as right-wing governments in Chile and Ecuador come under pressure to roll back market reforms.

In the wake of his win, Fernandez signaled that he would pursue close ties with leftist leaders in Mexico and Bolivia.

The election of Fernandez, who Brazil’s right-wing President Jair Bolsonaro has called a “red bandit,” sets the stage for a run-in between South America’s two biggest economies that could derail their Mercosur trade bloc.

Bolsonaro told reporters during a visit to Abu Dhabi that Argentine voters had made a mistake and he had no intention of congratulating Fernandez for his win.

U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said in a statement that the United States was ready to work with Fernandez to “address the interests our countries share.”

Fernandez faces a major challenge to revive Argentina’s economy, mired in recession for much of the last year, while fending off a rising mountain of debt payments amid concerns the country may be forced into a damaging default.

Investors will be on the lookout for signs about Fernandez’s economic policies, the make-up of his economic team and the role of Fernandez de Kirchner, who was president from 2007 to 2015.

Ratings agency Moody’s said on Monday the country was facing “substantial credit challenges” with limited funds, while the new head of the IMF, Kristalina Georgieva, tweeted the Fund looked forward to engaging with Fernandez’s administration.

Fernandez replied in a tweet saying Argentina “hoped to get out of this crisis as soon as possible and to grow again, so allowing us to fulfill our commitments as well as having a solid economy which benefits us all.”

The IMF extended a $57 billion credit facility to Argentina in 2018 to help the country meet its debt obligations. Some private investors are now concerned the Fund may drive a hard bargain if Argentina is forced into a restructuring.

On the streets, though, Fernandez supporters cheered the change in direction on Monday, pointing to economic malaise under Macri, which has hit people’s wallets across the social spectrum as domestic production and consumption has waned.

“The truth is that I am happy with the change, we did not want to keep going with the same government and hopefully things change a bit now for everyone because it was bad,” said Ramora Perez, 61, in Buenos Aires.

While Macri had looked to drive reforms to lower the fiscal deficit and lure foreign investment, those plans were scuppered in 2018 by a sharp downturn, while the collapse of the peso fired up inflation and pushed up interest rates to world-high levels.

That has caused a spike in issues such as poverty – now at above 35% – as well as hunger and homelessness, factors that are also exacerbating a rise in cases of tuberculosis.

Luis Alberto Coria, 19, a worker in the capital blamed the government for “bad economic policies.”

“This greatly affected working people and the middle class, practically destroyed it,” he said while sitting in a plaza in the city. “It is cause and consequence. The results that Macri has been dealt are well deserved.”