Kamarang is one of two best-known gold-mining locations in Region Seven’s Upper Mazaruni District. It is, as well, one of thirteen Amerindian villages situated at the confluence of the Kamarang and Mazaruni rivers, the others being Arau, Kaikan, Paruima, Waramadong, Kato, Jawalla, Phillipai, Chinoweing, Kato, Wax Creek, Imbaimadai and Isseneru.

Kamarang, however, is the location where myriad influences converge, notably, economic ones. The village extends almost precisely to the length of its contiguous airstrip and is home to a population of around six hundred persons. The half a dozen or so businesses that serve the community hug the perimeter of the airstrip. All of this is situated in an area known as The Government Compound. No one could tell us the length of the airstrip but its paved surface is believed to measure around 1220 metres. When we arrived there last week, an operation to extend the strip was in progress. Mining aside, some Upper Mazaruni residents are energetic farmers.

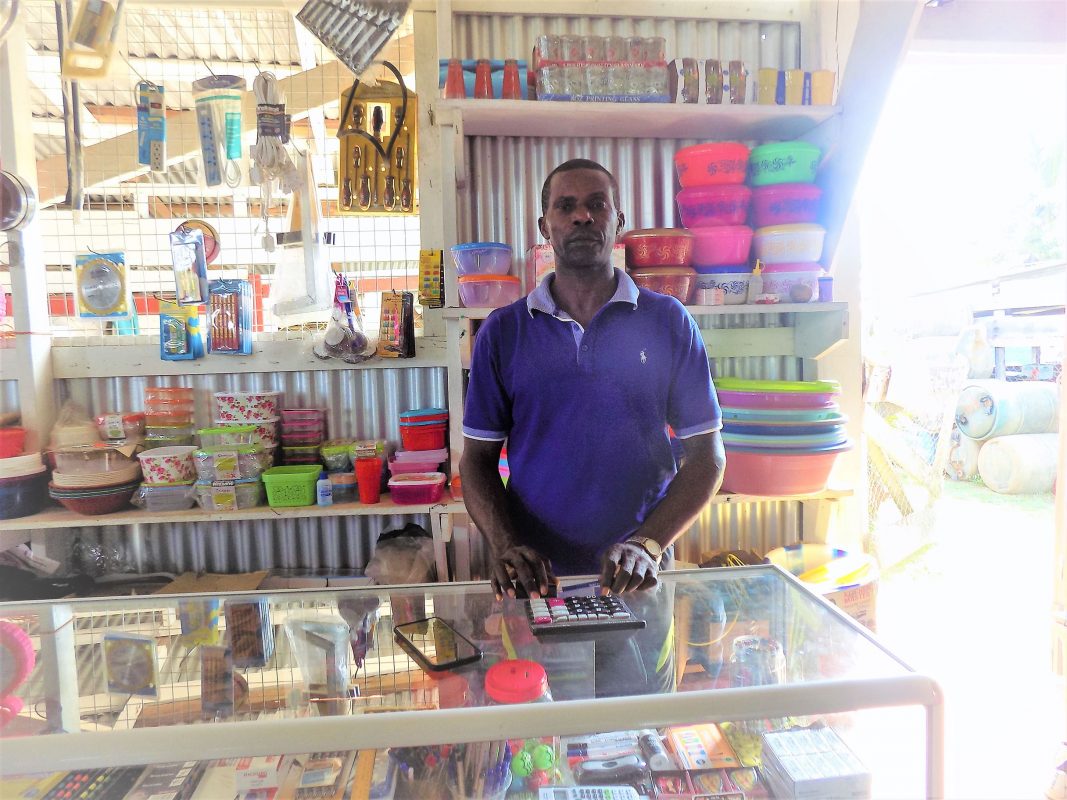

One might be forgiven for thinking that Reginald Sookram, the proprietor of Sookram and Hunter Trading is a native of Kamarang. Sookram and his family are embedded in the community. He went there, first, in 1993, as a Police Officer where he started a family. Afterwards, unwilling to be separated from his family on account of being reposted elsewhere, the Essequibo Coast-born Sookram opted to remain at Kamarang.

Sookram takes much of the credit for revolutionising business in Kamarang. When he went there, he said, there were hundreds of people with lots of money but relatively little to spend it on. At the time there were only three shops in the community. Simultaneously, his departure from the Force left him jobless.

The three shops that traded at the time offered basic survival items… salted meat, flour, sugar, rice, fuel and rum. “If persons wanted paint, zinc sheets, tools to work with, they had to order those and wait. While they waited much of the money was frittered away in revelry. Accordingly, Sookram decided that he would invest in the importation of a much broader range of goods into Kamarang, offering wider options and reducing the waiting time. In essence, he began to alter the commercial culture in the community. Items like kitchen sinks, tools, generators, building material and a range of household articles began to appear on the market. Those options, Sookram says, contributed to a change in social patterns. Not only was there a reduction in alcohol consumption but also a greater focus on initiatives designed to enhance the well-being of individuals and families in the community.

With several of the areas in the Kamarang ‘neighbourhood’ having been mined out miners have begun to move further away from the community. The shift has had a significant negative impact on business in the township, Sookram says.

Rudolph Wellington, another businessman operating in the Government Compound has been residing in Kamarang for 35 years. He owns a four-inch dredge but wound up his gold mining operation about three months ago. A point, he said, was reached where his returns were not covering his operating costs. Wellington says that there are around 35 dredges still located in the Kamarang area. He doubts that more than five of these are working at this time.

Alma Marshall, another dredge owner, also admits to having fallen on tough times. She now does a full-time job at a boutique and hardware store while her son now operates the family dredge. Alma says that people have now resorted to old-fashioned pork-knocking in the ‘mined out’ areas.

All of the miners with whom we spoke and who have fallen on tough times say that in order for fortunes to change, new mining areas will have to be opened up. That, they say, will take a considerable effort since thick vegetation will have to be cleared and huge trees felled in order to make more gold-bearing areas available.

There is no denying that commerce has declined at Kamarang… perhaps by as much as 40 per cent according to some estimates. These days, much of the routine commerce involves the limited spending by state employees, teachers, nurses and other public servants employed in the various villages in the Upper Mazaruni. At month’s end they usually converge on Kamarang to purchase mostly food. Even now, the shops in the Government Compound appear to be preparing for the December seasonal trading.

On the whole, Sookram says, the underpinnings of the mining culture persist. The continued underdevelopment of the interior areas of Guyana mean that transportation problems persist. Essential items are flown in to Kamarang and freight costs of around $130 per pound means that nothing is cheap. Some prices are worth mentioning. A 1.5 litre bottle of drinking water that would cost $300 in Georgetown costs $1,000 at Kamarang. A 20-pound cylinder of cooking gas costs $15,000 and a 17 kg sack of rice costs $4,800. Fish is retailed at $1,000 per pound, chicken at $700 a pound and beef at $900 per pound. A pound of onions or a pint of split peas can set you back $480 per pound and a loaf of bread costs $700. There is an alternative cheaper overland route for the movement of goods to Kamarang. One of the risks here, however, is that consignments may arrive at their destinations damaged. On the road there are logistical risks to be contended with.

Uncompetitive salaries make government jobs at Kamarang unfashionable. The knee-jerk option is to head for the ‘back dam’.

Paruima Village is good for farming though farmers face challenges occasioned by voracious ants as well as limited markets. The village’s fertile lands allow for the cultivation of cabbages, purple onions, beans, citrus, plantains, peanuts, boulanger, bora, squash, okra and ground provisions among others. Moving agricultural produce to market at Kamarang could take up to eight hours by boat. Forty gallons of fuel. In the past fuel was purchased from Venezuela. That has changed. The current economic situation there being what it is, fuel prices have shot up. These days, Sookram says, it may even be cheaper to purchase fuel directly from Georgetown.

The fortunes of the farmers are augmented by the schools’ Feeding Programme. The Waramadong Secondary School with its large resident student population purchases large quantities of farm produce.

The challenges associated with doing business at Kamarang are, Sookram says, rendered more bearable by the fact that the crime rate is modest. He says that stealing from businesses is virtually non-existent and the modest volume of traffic means that accidents are a rarity. In some respects and for all its challenges, there is an upside to Kamarang, he says.