MANAGUA, (Reuters) – When Nicaraguan police pulled over his luxury SUV, businessman Jose Adan Aguerri thought it was a routine traffic stop.

Suddenly, a group of men rushed the vehicle as the cops stood by and watched. Rocks pounded the car. A large ball bearing shattered the driver’s side window. Aguerri hit the gas and escaped.

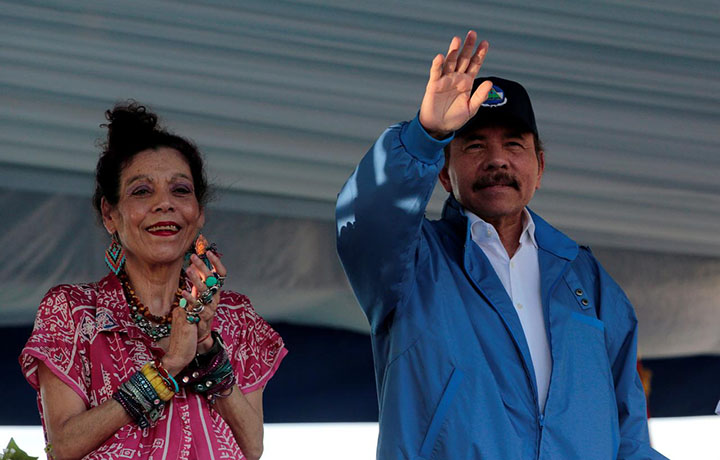

Recalling the September incident in the western city of Leon, which was corroborated by three passengers and mobile phone footage, Aguerri said he has no doubt who ordered the attack: the government of leftist strongman Daniel Ortega.

“It was a message to the private sector,” said Aguerri, the leader of Nicaragua’s most influential business association, the Council for Private Enterprise (COSEP).

The government and the police did not respond to requests for comment about Aguerri’s allegations.

What’s clear is that an unorthodox alliance between Ortega, a former Marxist guerrilla, and the nation’s most powerful capitalists has splintered. After a decade of working with the president to grow the economy, the business elite are now looking to unseat him after a violent state crackdown on anti-government protesters left around 325 people dead last year. More than 2,000 people were injured and around 600 jailed.

Ortega’s well-heeled adversaries include about a dozen of the nation’s wealthiest families known as the “gran capital.” Two people in this exclusive group, whose members rarely speak with the media, talked to Reuters, as did six prominent business people. Most declined to be identified for fear of retribution. If Ortega does not heed calls by his opponents to step aside, they say they will fund opposition candidates in the next election, an effort some estimated could cost $20 million to $25 million.

“Money will start flowing. There is no doubt,” one businessman from a gran capital family told Reuters.

Political strife has battered the economy of this Central American nation of 6.2 million people. And it threatens the relative stability of a country that has largely avoided the mass out-migration plaguing its neighbors. Nevertheless, more than 80,000 Nicaraguans have fled the country since protests began in April 2018, according to the United Nations. Ortega, whose term ends in January 2022, has derided his adversaries as coup-plotters and terrorists. He and his allies have denounced Nicaragua’s corporate elite as tax dodgers and “enemies of the people.”

Business people who criticized Ortega publicly say they have lost public contracts and had their enterprises investigated by tax authorities. Some say they have received death threats and had land seized by armed pro-government militias.

Michael Healy, a commercial fruit farmer and senior COSEP member, said these groups now occupy about 4,000 hectares of private land, including three of his family’s farms that were invaded last year.

“(The pressure) is not going to work,” said Healy, who said he was in the SUV with Aguerri during the September attack. He said the alleged intimidation has only hardened his resolve to change Nicaragua’s government.

Ortega remains in control. Still, unrest in other parts of Latin America, including this month’s toppling of Bolivian President Evo Morales, Ortega’s leftist ally, has heightened tensions in Nicaragua.

In recent days, 16 Nicaraguan women launched hunger strikes in two churches, including the cathedral in the capital Managua, to press for the release of relatives they say were jailed for protesting Ortega’s rule. Police quickly surrounded the churches and arrested 13 activists who brought water to the hunger strikers. Authorities later charged the activists with trafficking weapons, charges the United Nations has called “trumped up.”

“People like Ortega who have somewhat questionable grip on power are nervous,” said Javier Gutierrez, a regional analyst and former trade diplomat. “It’s a very delicate situation.”

‘SLOW COOKER THAT EXPLODED’

Animosity between Nicaragua’s wealthy and 74-year-old Ortega isn’t new.

A Cuba-trained former rebel commander, Ortega was part of the resistance that ousted dictator Anastasio Somoza in 1979. Ortega’s Sandinista National Liberation Front, or FSLN, nationalized banks and seized holdings of industrial moguls and land barons while battling U.S.-backed Contra forces attempting to overthrow the new socialist revolutionary government.

Elected president in 1984, Ortega was voted out of office after a single five-year term as the economy floundered. The business elite, many of whom had fled abroad, watched nervously as Ortega was re-elected in 2006.

This time he wooed them with a business-friendly agenda. COSEP members were appointed to a slew of government boards, where they helped draft pro-market legislation.

Critics say the business elite said little as Ortega abolished presidential term limits and gained control of the courts and police.

“They just wanted to keep doing business, which isn’t a crime, but they didn’t realize the price they were going to pay for that in terms of damage to democracy,” said Eduardo Enriquez, the editor of La Prensa, Nicaragua’s biggest newspaper.

Aguerri said COSEP did challenge Ortega’s moves to weaken institutions, and that it chose to engage with his government to help Nicaragua. Between 2010 and 2017, Nicaragua’s economy expanded by about 5% annually, one of the fastest rates in Latin America. Foreign investment poured in.

But the good times ended abruptly last year. What began as demonstrations by retirees challenging social security taxes morphed into wider dissent against Ortega’s rule. Televised images showed police shooting unarmed protesters, and pro-government militias assaulting pensioners and students with baseball bats.

The Organization of American States denounced state-led violence as “crimes against humanity.” The United States imposed sanctions on Ortega’s family and allies.

Ortega says Western powers engineered the demonstrations to topple his democratically elected government.

Nicaragua’s economy contracted 3.8% last year and is expected to shrink another 5% this year, according to a World Bank forecast.

“We were so blinded by this growth and stability and security,” said a member of a prominent business family in northern Nicaragua. “It was like a slow cooker that exploded.”

AID TO POLITICAL PRISONERS

Five Nicaraguan magnates, including billionaire Carlos Pellas, owner of the Grupo Pellas conglomerate, held private talks with Ortega earlier this year. They urged the government to negotiate with the Civic Alliance, a coalition that includes students, farmers and civil society groups as well as COSEP.

But those discussions broke down. COSEP says it is no longer in communication with the government.

Businessmen say they’re now focused on bankrolling an opposition candidate in the hopes of defeating Ortega at the polls.

To have a chance, the opposition would need to settle on running a single, unity candidate to avoid splitting the vote. But any candidate deemed close to the gran capital would likely be shunned by the poor, who make up the bulk of the electorate and view Nicaragua’s entrenched elites with suspicion, said Enriquez, the La Prensa editor.

“After Ortega, big business is the second most mistrusted figure in politics,” he said.

Wealthy Nicaraguans did help pay medical bills and legal fees of some protesters, three prominent businessmen told Reuters.

Assistance to anti-government demonstrators has earned the enmity of Ortega, who has condemned “those who are financing terrorism.” His government last year passed sweeping anti-terrorism laws with lengthy prison penalties.

Business leaders say they worry that legislation will be trained on them as they build a war chest to defeat him.

“It’s going to get nasty,” a Nicaraguan businessman said.