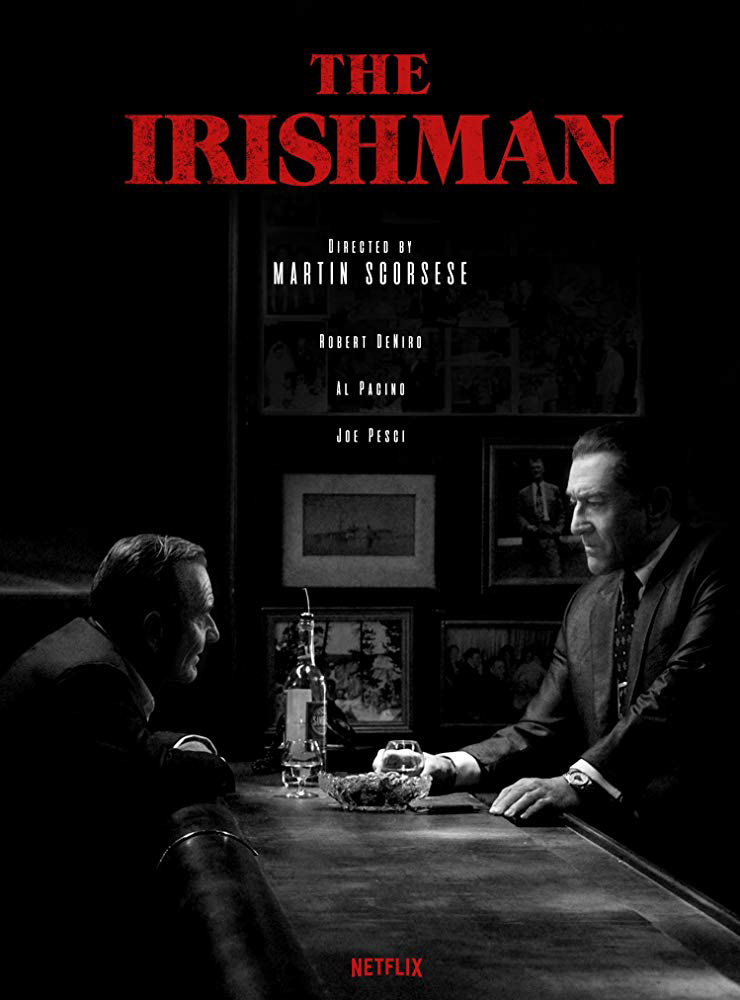

![]() It’s hard not to think of Martin Scorsese’s newly released “The Irishman” as a film that looks backward. This long-gestating passion-project, recently released on Netflix, sees Scorsese returning to familiar territory – mobsters. At 77, Scorsese is a giant of contemporary cinema so that any work he releases seems loaded with context. It seems as much a feature of the work, as it is a bug of our relationship with Scorsese that it feels natural to read everything new thing he does in relation to what came before. But context does overwhelm “The Irishman”. At three-and-a-half hours, it’s the longest Scorsese film by a significant margin. It sees him returning to his frequent lead-actor Robert De Niro. And, although he’s moved across themes and genres, he’s been marked as a crime-film director in ways that make the themes of “The Irishman” seem expected and inevitable. For Scorsese detractors, this is old-boring Scorsese, doing yet another mob-movie. But, for all the casual dismissal of the film as regular Scorsese fare, and in all the ways that the “The Irishman” flirts with the past, the film is also very explicitly a 2019 film. For all the illusion of the film being a return to the past, Scorsese reaching for familiar modes, DeNiro and Pesci and Pacino returning to familiar genres, this is a film that overtly and uncomfortably digs at the present, at legacies, and at fate.

It’s hard not to think of Martin Scorsese’s newly released “The Irishman” as a film that looks backward. This long-gestating passion-project, recently released on Netflix, sees Scorsese returning to familiar territory – mobsters. At 77, Scorsese is a giant of contemporary cinema so that any work he releases seems loaded with context. It seems as much a feature of the work, as it is a bug of our relationship with Scorsese that it feels natural to read everything new thing he does in relation to what came before. But context does overwhelm “The Irishman”. At three-and-a-half hours, it’s the longest Scorsese film by a significant margin. It sees him returning to his frequent lead-actor Robert De Niro. And, although he’s moved across themes and genres, he’s been marked as a crime-film director in ways that make the themes of “The Irishman” seem expected and inevitable. For Scorsese detractors, this is old-boring Scorsese, doing yet another mob-movie. But, for all the casual dismissal of the film as regular Scorsese fare, and in all the ways that the “The Irishman” flirts with the past, the film is also very explicitly a 2019 film. For all the illusion of the film being a return to the past, Scorsese reaching for familiar modes, DeNiro and Pesci and Pacino returning to familiar genres, this is a film that overtly and uncomfortably digs at the present, at legacies, and at fate.

It is not surprising then that the film begins in a retirement home. The camera moves through a hallway, circling a man in a chair until we finally see him – old and wizened, but not exactly warm. This is Frank Sheeran, and we will spend the next 210 minutes with him as he begins to tell us his story. It’s a familiar hook: seasoned criminal looks back on his life. But as “The Irishman” goes on, Frank’s narration being the filter for this story comes to feel more and more than merely an expedient narrative tool. As Frank tells us his life, in the non-linear fashion that seems tied to an older-mind, we see him moving from unassuming truck-driver to hired-hitman and the film seems to be wrestling with his relative passivity in his own fate. It’s one of the numerous little ironies of the film. A hitman hardly seems like a passive job, and yet, the way that Frank positions himself in his story seems to be predicated on pure serendipity – a man lucky to be in the right place at the right time around the right people. And then successively in the wrong place. At the wrong time with very wrong people.

A lot will happen over the course of his life. Frank will become the protégée of Russell (an excellent Joe Pesci), he will become a conduit for many important men in the mob and enjoy a fairly successful professional life. But two sections stand out: one is Frank’s relationship with Teamsters president Jimmy Hoffa and the other is his icy, willowy relationship with his silent daughter, Peggy. But, neither of these arcs come to us first and instead “The Irishman” is deliciously dependent on what is excluded as much as what is included. The way this story is told becomes inextricably linked to what the story is telling us, and what it is not telling us.

It is a story within a story within a story. Time in the film is imprecise and malleable at a level that is both instructive and troublesome, especially at first. The film is working on three timelines. The first is an aging Frank telling his story; the second is a younger-but-still-old Frank on a trip with a Russel to a wedding – the importance of which we don’t realise until much later; and the third is the actual sort-of linear story of how Frank came to a life of crime. It’s like a story within a story within a story, which at first seems incredibly chaotic but reveals itself as predicated by the residual inarticulation of the person telling the story. Entire decades go by with a single line of dialogue, an entire half-an-hour is spent on a day. By the end of the film, when the three timelines have intersected to give you a sense of purpose, “The Irishman” leaves us to consider the life and legacy of Sheeran, and it is in that final hour that the film puts forward its central question: what is a life really for?

It’s the same question that Scorsese was asking three years ago at the end of “Silence”. When “Silence” premiered in 2016, it seemed to be deliberately engaging with Scorsese’s “The Last Temptation of Christ”. It was a kind of reassessment of Scorsese’s own Catholicism. That “The Irishman” comes on the heels of that film, also engaging with a decades-old Scorsese film (“The Irishman” is very reminiscent of “Goodfellas”) feels immediately important. It is as if Scorsese is relitigating his own artistic impulses. Both films interrogate the value of one’s convictions, spinning a tale about a man who must come to face the ethical decisions of his life, told with a formal rigour that is both aesthetically deliberate and thematically grandiose, leaving you with an emotional wallop that feels like cudgel to the head. “Silence” pushes that melancholy a bit further, uncomfortably confronting us with dangers of doubt as if Scorsese himself must justify his own existence. “The Irishman” seems less thoughtful, only by comparison, but it’s thematically risky and cogent in ways that become distressing over time.

It’s true that some of this emotional effect feels baked into to the who and what of the film. It feels impossible to read “The Irishman” as independent of the expressiveness of Scorsese’s own place within film history. It’s been some time since he’s done a gangster film and that this film caps his decade, “The Irishman” feels loaded with implications. The value of the film’s performances is more than the chance to see these actors giving purposive performances – instead every frame of the film seems bathed in melancholy. This is a requiem for a life and lifetime that has ended. And not a second too soon.

What’s significant about Scorsese’s piercing of the audience’s emotions in “The Irishman” is the deployment, though. The emotional weight that the film builds up to and ends on is not one that invites us to partake in or identify with Frank’s remorse or grief. Instead, “The Irishman” offers a different, stranger take on what becomes a tragedy. The film’s overarching emotional aesthetic is its own awareness of the emptiness that feels inherent in its protagonist – we are moved by the profundity of absence and the unrewarding emptiness of silence. And it’s why everything, even the large arc of convenient friendship between Jimmy and Frank, feels perfunctory. Not because this part of the film isn’t excellent, in fact Al Pacino as Jimmy Hoffa – digging deeply all bluster and yelling, but also charm and inveigling – turns in the film’s most rewarding performance playing into and against our ideas of what makes a Pacino performance. And even though the fate of Jimmy and Frank is the most technically astute moment of the film, it’s all in service of Scorsese’s larger point about the ways that being a good man is predicated on a man’s relationship with his children.

Content affects form here and Peggy (Lucy Gallina as a child and Anna Paquin as an adult) is given limited dialogue but the pregnant glances exchanged between her and her father, the way that Scorsese keeps returning to her face, as the film’s real emotional pillar And as the film goes on, it becomes clear that the way that Frank’s narration deliberately avoids interrogating this is meant to be subverted by the film’s own uncomfortable lingering on it. In a late scene he has an awkward exchange with another daughter where he tries to articulate his ineffective parenting. His inability to string a coherent sentence together directly invokes a similar moment from a few scenes earlier where he makes a significant phone call and cannot put together a sentence. In both cases, Frank is asked to look within himself to collect a smattering of feeling or empathy. And he cannot. There’s nothing there. Guilt, despair, contrition. These are emotions that one can do something with. But emptiness? Resignation? Scant fruits for interrogation. And, that is all Frank can offer us.

Towards the end of the film, an aged Frank asks a nurse in a daze: “It’s Christmas?” The line is a throwaway one but it feels like the saddest line, announcing the way that time has creeped up on Frank, unbeknownst to him. For Scorsese, there is nothing more terrifying than a life wasted, and “The Irishman” invites us to watch as the bell tolls for this hollow man – unable to find contrition or hope, but fated to a long life with only his memory to keep him alive. Like with “Silence”, “The Irishman” find Scorsese in a state of rumination, like a man considering his legacy. And in both, he turns that question of legacy inward to himself and his characters, but outward to his audience. Is there really any meaning to your life?