Climate change is no longer a long-term problem. We are confronted now with a global climate crisis. And the point of no return is no longer over the horizon. It is in sight and is hurtling towards us… Our war against nature must stop and we know that death is possible…

Climate change is no longer a long-term problem. We are confronted now with a global climate crisis. And the point of no return is no longer over the horizon. It is in sight and is hurtling towards us… Our war against nature must stop and we know that death is possible…

We simply have to stop digging and drilling, and take advantage of the vast possibilities offered by renewable energy and nature-based solutions…Do we really want to be remembered as the generation that buried its head in the sand, that fiddled while the planet burned?

United Nations Secretary-General António Gutteres

A report on climate change presented to the 25th Meeting of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in Madrid, Spain, painted a gloomy picture for the future of our planet. The key findings are:

(a) It is almost certain that in the last decade (2010-2019) average temperature will reach the highest on record;

(b) Sea water is 26 percent more acidic than at the start of the industrial era, thereby degrading marine ecosystems;

(c) Arctic ice reached record lows in September and October of this year. Antarctica has also seen lows several times during the year;

(d) Climate change is the main cause of the recent rise in global hunger, affecting some 820 million people in 2018; and

(e) Weather-related disasters displaced millions of people this year and affected rainfall patterns from India to northern Russia and the central United States, and many other regions.

According to the World Meteorological Organisation, ‘heatwaves and floods which used to be “once-in-a-century” events are becoming more regular occurrences. Countries ranging from The Bahamas to Japan to Mozambique suffered the effect of devastating tropical cyclones. Wildfires swept through the Arctic and Australia’. And according to the UN Secretary-General, the world must choose hope over surrender in the fight against climate change, and governments risk sleepwalking past a point of no return.

In last week’s article, we reported a Government official saying that it is necessary to keep Parliament open in the event GECOM needs additional funds. We had stated that the Commission’s budgetary allocation for 2019 was $5.371 billion compared with $2.257 billion allocated in 2018, a 238 percent increase. The Minister of Finance had explained that this significant increase was to ‘facilitate early preparations and to ensure the smooth conduct of these most important elections’. We had further stated that since elections will not be held in 2019, GECOM should have surplus funds even after taking into account expenditure incurred on the aborted house-to-house registration and that any surplus as at year has to be surrendered to the Consolidated Fund. In fact, on 23 May 2019, the National Assembly approved an additional $3.496 billion by way of Supplementary Estimates, which gives a revised allocation of $8.867 billion. This reinforces our suggestion that the reason given for keeping Parliament open lacks merit, leaving citizens to speculate as to the real motive for not dissolving Parliament. GECOM has now confirmed that it does not need any additional funds for conducting the 2 March 2020 elections. Did the Administration not consult with GECOM before deciding to keep Parliament open?

Now for today’s article. The Integrity Commission Act was passed in 1997 in compliance with the Inter-American Convention Against Corruption of which Guyana is a signatory. It main purpose is to secure the integrity of persons in public life.

Person in public life

There is mistaken belief by some persons that the Act applies only to Ministers of the Government and MPs. However, the Interpretation Section makes it clear that a person in public life is one ‘who holds any specified office and includes a person in section 42, whether or not mentioned in Schedule I’. Section 42 lists the following persons: (i) public officers; (ii) officers of the Regional Democratic Councils, Bank of Guyana, State-owned/controlled banks, public corporations and other entities in which controlling interest vests in the State; and (iii) members of the various tender boards.

Schedule I identifies specific persons to be included in the list of persons in public life. This includes, the President; Speaker of the National Assembly; Ministers of the Government; Members of Parliament; Permanent Secretaries; Regional Executive Officers; Director of Public Prosecutions; judges and magistrates; Auditor General; Finance Secretary; Commissioner of Police; Chief of Staff of the Guyana Defence Force; Commissioner-General of the Guyana Revenue Authority; heads of diplomatic missions of Guyana; heads of all government departments; and heads of public corporations and other entities in which controlling interest vests in the State.

Also, to be included in the list, are all procurement officers, as provided for under Section 24(3) of the Procurement Act. This section deals with procurement by public corporations and certain other bodies. It states that ‘[e]mployees of any procurement entity who by virtue of their job description are responsible for procurement shall declare their assets to the Integrity Commission’.

One hopes that all the above persons and their senior management teams are included in the Commission’s database.

Specific responsibilities of the Commission

The Commission’s specific responsibilities are:

(a) To receive and examine annual declarations of income, assets and liabilities of all persons in public life, including those of their spouses and children;

(b) To make enquiries as the Commission considers necessary to verify or deter

mine the accuracy of the submissions, and to request additional information, if needed;

(c) To conduct a formal inquiry in relation to a particular declaration;

(d) With the consent of the Director of Public Prosecutions, to initiate prosecution

against any person in public life who fails to make a declaration or who submits incomplete information, despite a request for the person to correct the deficiency;

(e) To receive complaints from any person in relation to breaches of the Code of Conduct, determine their merit or otherwise, hold public inquiries in the event a complaint has merit, and submit a report to the DPP and/or the relevant government agency on the results of the inquiry;

(f) To be provided with information about any gift received by a person in public

life that exceeds G$10,000 in value and to determine whether such a gift is personal or State property; and

(g) To submit to the President within three months of the close of the calendar year

an annual report outlining the various activities undertaken during the calendar year,

including any difficulties experienced in the discharge of the Commission’s functions. The report is to be laid in the National Assembly within 60 days of its issue.

After a prolonged period of dormancy during the years 2006 to 2017, the Commission was re-activated in February 2018 with the appointment of a chairman and three commissioners.

Publication of list of defaulters

In November 2018, the Commission began to publish the names of persons who had not filed their declarations of income, and assets and liabilities. Section 13(1) of the Act requires all such persons to do so not later than 30 June in respect of the preceding 12-month period, failing which their names would be published in a daily newspaper and in the Gazette, as provided for by Section 19. In our article of 27 May 2019, we had stated that the Commission needs to go beyond publicizing the names of defaulters if it is to play a more meaning role in preventing and fighting corruption in government.

Last week, the Commission’s Chairman disclosed that the Commission has been unable to publish the names of defaulters for the period ended 30 June 2019 because of a lack funds and that he raised the matter with government officials to no avail. It would have been close to six months since the deadline has passed, and the Commission did not see it fit to alert the public earlier about its inability to discharge this important responsibility. Considering its increased staffing in 2019, the Commission should have been in a position to compile the list of defaulters for publication not later than the end of July 2019.

Last week, the Commission’s Chairman disclosed that the Commission has been unable to publish the names of defaulters for the period ended 30 June 2019 because of a lack funds and that he raised the matter with government officials to no avail. It would have been close to six months since the deadline has passed, and the Commission did not see it fit to alert the public earlier about its inability to discharge this important responsibility. Considering its increased staffing in 2019, the Commission should have been in a position to compile the list of defaulters for publication not later than the end of July 2019.

Budgetary allocation for 2019

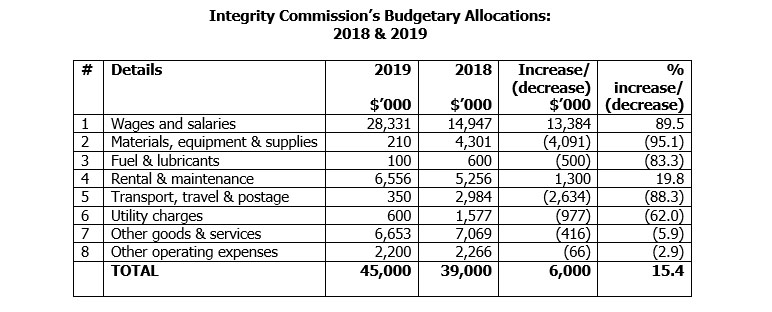

Section 11 of the Act provides for the financing of the operations of the Commission to be met from funds provided by Parliament via an Appropriation Act. Shown below is the Commission’s budget allocation for 2019, compared with 2018:

Although on an overall basis, the Commission’s budget increased by 15.4 percent in 2019, of the eight line items comprising its budget, six items have seen reductions varying from 2.9 percent to 95.1 percent. The two line items from which the cost of publication of the names of defaulters are normally made are Other goods and services, and Other operating expenses, which have a combined allocation of $8.853 million. Despite their reductions, it seems reasonable to suggest that in view of the Commission’s core activities being the monitoring of the financial returns of officials and publishing the names of defaulters, a significant portion of this amount should have been set aside for such publication.

The two items for which there have been in increases are Wages and Salaries – 89.5 percent; and Rental and Maintenance – 19.8 percent. In relation to the former, the staffing has increased to eleven, excluding the three Commissioners and the Chairman who serve on a part-time basis. As regards the latter, the Commission’s offices are located in Subryanville in a rented building.

Conclusion

It is rather unfortunate that, considering the Integrity Commission’s overall mandate of securing the integrity of persons in public life as well as its specific responsibilities as outlined above, the Administration has seen it fit to reduce its budgetary allocation. Is it a reaction to publication of the list of defaulters in November 2018 which includes key Ministers of the Government and some MPs? This raises the important question of whether the Commission should not be given Constitutional status to ensure as far as possible that it is safeguarded in terms of the availability of adequate funds to discharge its mandate. It seems inappropriate, indeed ironical, for some of the persons who are required to declare their income, assets and liabilities to the Commission to be the very ones to decide on the allocation of financial resources to this important anti-corruption body.