By Aminta Kilawan-Narine

Aminta Kilawan-Narine is an attorney, community activist, and co-founder of Sadhana: Coalition of Progressive Hindus, which is committed to promoting social justice through the values at the heart of the Hindu faith. In 2015, Aminta began writing a column for The West Indian.

Aminta Kilawan-Narine is an attorney, community activist, and co-founder of Sadhana: Coalition of Progressive Hindus, which is committed to promoting social justice through the values at the heart of the Hindu faith. In 2015, Aminta began writing a column for The West Indian.

On the night of Friday, November 8th, 27-year-old Donna Dojoy (Rehanna) was stabbed to death by her husband Dineshwar Budhidat in Ozone Park. Budhidat subsequently committed suicide, hanging himself on a tree at Spring Creek Park of Jamaica Bay in Howard Beach, Queens. The incident almost directly mirrors the tragedy of Stacy Singh, who was murdered by her husband before he too committed suicide by hanging. Singh’s death was the first homicide in New York City in 2018. This past September, Marian Singh-Loftis was killed by Budhnaraib Kadar in Schenectady, New York, where a large Indo-Caribbean community resides. In recent years, several other Indo-Caribbean women in New York City were murdered by those who should have loved them. Rajwantie Baldeo, Natasha Ramen, Guiatree Hardat, and Amarita Khan are among them. Many others still suffer in silence.

Domestic violence has no face. It can impact people across the socioeconomic spectrum and is not relegated to any one group of people. Yet there is no denying a pattern of behaviour among Indo-Caribbean domestic violence incidence. Newspaper articles from the Caribbean feature articles of brutal murder/suicides primarily happening in Guyana and Trinidad, but this phenomenon occurs in New York City also, primarily among those who recently migrated to the United States. It is fair to say that the root causes of domestic violence in our community transcend migrations and generations.

Domestic violence has no face. It can impact people across the socioeconomic spectrum and is not relegated to any one group of people. Yet there is no denying a pattern of behaviour among Indo-Caribbean domestic violence incidence. Newspaper articles from the Caribbean feature articles of brutal murder/suicides primarily happening in Guyana and Trinidad, but this phenomenon occurs in New York City also, primarily among those who recently migrated to the United States. It is fair to say that the root causes of domestic violence in our community transcend migrations and generations.

Domestic violence against women has been prevalent in the Indo-Caribbean community since Indian indentureship. In a 2010 Ms. Magazine article, Indo-Guyanese American writer Gauitra Bahadur traced these killings to colonial times, when “indentured laborers on the plantations, suspecting their wives of infidelity, hacked the women to death with their cutlasses, the long, curved blades used in the fields to cut sugarcane.” A century later, Bahadur notes, “cutlass killings” still occur.

Guyana’s first comprehensive national survey on gender-based violence released just last month revealed that 55 percent of all women experienced some form of violence, with at least 10 percent of the violence perpetrated by an intimate partner. It is this violence that has trickled into Richmond Hill, Schenectady and other Indo-Caribbean hubs, resulting in the deaths of women like Dojoy, Singh, Baldeo, and Singh-Loftis.

The most brutal of the domestic violence cases the New York City Indo-Caribbean community has seen has happened to working class women. Dojoy was a bartender at Gemini Ultra Lounge on Liberty Avenue and 107th Street in Richmond Hill. In December 2017, Rajwantie Baldeo, who worked at The Oasis restaurant on Liberty Avenue and 123rd Street, was practically decapitated by her husband.

It feels like with at least every passing year, we lose another Indo-Caribbean woman at the hands of violence. Many more women are being abused day after day. Their stories often are not heard. They often do not know where to turn. What can we do as a community to stop the violence once and for all?

We need to raise sons who will respect women and daughters who can spot abusive behaviours early on. This also means showing wives the same level of respect that we show our daughters. Gender norms and behaviours trickle down generation after generation. We need to do better at teaching our sons and daughters what it means to be in a healthy relationship. Additionally, we need to apply the same standards to our own relationships. We raise our daughters to chase after their dreams, to pursue careers, to be who they want to be. Yet, the standards are often different for wives. This is hypocritical and it perpetuates a patriarchy that continues to plague our people. When our children see this culture continue, they think it’s okay to also be in an abusive relationship. This must stop.

Wrap-around services for survivors are sorely needed. One of the reasons women stay in abusive situations is because they’re afraid of what the alternative could look like. Would leaving mean they have to uproot their lives and their children’s lives? Would it mean they have to live in a homeless shelter? Would it mean their abuser will try to get them deported? How will they pay their bills? Will their characters be permanently marred? These are real questions that survivors of domestic violence ask themselves. There are too few culturally-appropriate places that cater to these questions, too few supports in place to give survivors an assuring path to safety. We need to work with existing infrastructure provided by the City and well-resourced non-profit organizations to develop paths for Indo-Caribbean survivors.

Victim blaming is unacceptable, no matter what the circumstances are. We make excuses for abusers, even those who commit murder. A Daily News article quoted a cousin of Budhidat stating, “he’s the coolest, calmest, funniest guy.” Some have said that Budhidat should have known what to expect because his wife was a bartender. A New York Post article implied that Budhidat murdered his wife because she had a crush on Bollywood actor Hrithik Roshan. The sensationalizing of this incident distracts from the bottom line. There is never an excuse for any kind of violence. There was nothing wrong with choosing bartending as a profession. In Stacy Singh’s case, there was nothing wrong with having red hair, yet some community members used Singh’s hair as a justification for her murder. Demonizing victims/survivors and humanizing abusers is common. This is appalling.

Abusers need to learn why their behaviour is wrong. We know the statistics. It takes approximately seven attempts until a survivor is able to successfully leave her abuser. There are possible ways to intervene during that time before it’s too late. Many abusers, for example, have already had run-ins with the law. This was not Budhidat’s first offence against Dojoy. He was previously arrested for strangulation, just last August, one month after he and Dojoy wed. Dojoy even had an order of protection against him. That order didn’t protect her. Today, she is no more. There are programmes that the Queens County Criminal Court often requires of domestic violence perpetrators as part of their punishment. Court-mandated programmes like batterer’s intervention have the potential to shift the ways in which perpetrators think and behave. Too many opportunities are missed in the design of these programmes, however. Generally, they often function as simple checks on a box for a judge. If more resources were put into building out programmes that have been empirically deemed effective, abusers would have a check on their toxic masculinity. As an aside, when I interned at the Queens Family Justice Center in law school, I sat in arraignments, namely the first time a defendant sees a judge after being arrested. In the domestic violence court room, I’ve honestly never seen more defiant abusers than Indo-Caribbean men, who simply don’t understand how wrong their actions are. My head fell in shame during those moments.

A robust community network must be built. Survivors can be hesitant to entrust their personal stories to professionals in order to access help. This is especially the case when professionals are not culturally-appropriate. Moreover, sometimes involving the police does more harm than good, further inciting anger in the abuser. Building out an Indo-Caribbean community network of trained volunteers willing to help both in crisis situations as well as non-crisis situations is critical. Survivors need to know they’re supported by their own people. Abusers need to know they will be held accountable by their own.

We need to take to the streets. Historically, some of the biggest movements to promote women’s rights occurred after massive uprisings of women to stand up for justice. If we are to seek a true cultural shift, then we must build a movement of women, as well as men allies, to take to the streets and send a message far and wide that gender-based violence will never be acceptable, and that we will hold abusers accountable for their actions. To this end, some of us will be organizing a Women’s March in South Queens later this year.

Private and community conversations matter. We can disrupt the oppression if we start having hard conversations about gender-based violence whenever possible, even (and especially) at the dinner table. This also means talking about our feelings and getting the mental health help we might need. Men in our community often bottle up their inner emotions because of learned behaviour taught to them from the time they were small children. That needs to change. We also need to have wider community conversations about gender-based violence. The only way to ascertain what tools and resources our people need to end the cycle of violence is to ask them directly, and to meet them where they are.

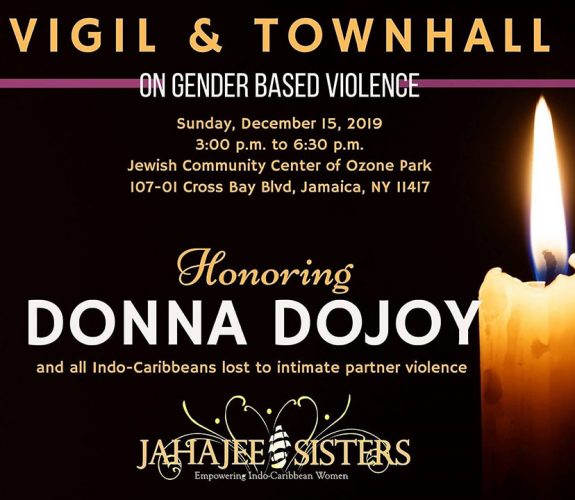

Jahajee Sisters, an organization that was founded to address gender-based oppression in the Indo-Caribbean community, is organizing a vigil to honour Donna Dojoy on December 15th, 2019 from 3pm to 6:30pm at the Jewish Community Center of Ozone Park located at 107-01 Cross Bay Blvd, Jamaica. NY 11416. The event will include a town-hall discussion where attendees can strategize ways to create community solutions to ensure this type of violence never happens again. The vigil and town hall are co-sponsored by Caribbean Equality Project; Chhaya CDC; Sadhana: Coalition of Progressive Hindus; Desis Rising Up and Moving (DRUM); United Madrassi Association; the Shakti Mission; and Shri Shakti Mariammaa Temple. For more information, email jahajeesisters@gmail.com

Donna Dojoy 27, was fatally stabbed in Queens, NY by her husband on November 8, 2019, before he committed suicide.