![]() This review contains mild spoilers for the film.

This review contains mild spoilers for the film.

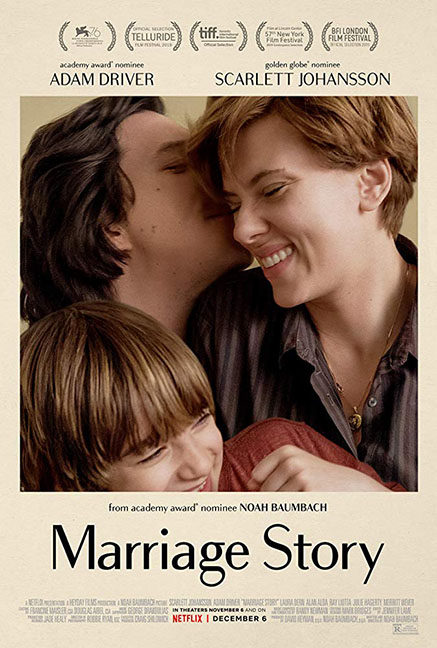

In the ironically titled “Marriage Story”, Nicole (an actress, played by Scarlett Johansson) and Charlie (a director, played by Adam Driver) try to navigate the end of their marriage and custody of their eight-year-old son. Their imminent divorce is an irrefutable fact from the beginning of the film. Nicole is leaving Charlie’s theatre company in New York to star in a pilot for a TV series in LA. Yet, despite the dissolution of their personal and professional relationship (she’ll be leaving the lead-role of Charlie’s play, which we see her acting in early on) Nicole insists that Charlie give her his directorial notes after her final performance. She knows it’ll bug him if he doesn’t. And so, he does: her posture was off in a scene, and she was pushing for the emotion at the end. In the brief silence after his notes, he awkwardly intones, “Thanks for indulging me.” She responds with a clipped, “Goodnight Charlie.” The idea of indulgence has stuck with me since I first saw the film at its Toronto International Film Festival premiere in September. I circled the line in my notebook, musing at the way it seemed so incidental and yet so incredibly precise as a distillation of what’s at work and at stake here.

“Marriage Story” after all, is not just a fictional divorce story. Noah Baumbach, who writes and directs the film, acknowledges the way his well-publicised divorce from actress Jennifer Jason Leigh bled into the script, although he’s careful to point out that beyond his real-connection to the script the film is about more than just his marriage and divorce. Yet, for many, “Marriage Story” is Baumbach’s life writ large. Charlie is a genius director (multiple characters insist he is) laid bare by his wife who means well but needles him into an unnecessarily messy divorce. For many, to engage with “Marriage Story” is to indulge Baumbach. The film is not a fictional narrative but a presentation of how Baumbach sees himself, endlessly sympathetic despite his infidelity in marriage. It is yet another divorce narrative filtered through a male lens (Baumbach directed “The Squid and the Whale,” inspired by his own parents’ divorce), it’s yet another story where the character’s are not normal but rich enough to fly back and forth from LA and NY, it’s another film that’s cripplingly filtered through its whiteness and its heterosexuality, and yet “Marriage Story” through its overwhelming specificity feels profound and focused in a way that resists this kind of flattening of its value.

For “Marriage Story” is best understood and appreciated as an incredibly nuanced take on marriage and people. Even as audiences have felt the need to choose sides, either Team Charlie or Team Nicole, the film is deliberately working to offer a tale of divorce that is less about who is indictable and more about the inevitable reality of people who cannot be together. Yet, because “Marriage Story” is a Netflix film, social media has been littered with numerous high-resolution videos and screencaps – shared, and reshared – extolling its virtues, and its limitations. Close-reading, for all its value, means little when it’s removed from contextual importance so it’s made for a familiar, but annoying, kind of armchair criticism distilling the film down to individual moments. A central moment is a late-film, climactic encounter where Nicole and Charlie – driven to shorn resentment and anger after unhappy divorce proceedings – confront the worst of each other in a scene of angry yelling. The hot takes were legion: This is great acting; no this is terrible acting; no, this is great acting because of how terrible it comes across; the writing is terrible; Noah Baumbach is a self-involved hack. It was exhausting, a wilful misreading and obfuscation of intent that has become normal in critical and cultural parlance in the last decade, and yet the hot takes – flattening the intentions of these characters, turning them into caricatures of privilege – seemed weirdly instructive. “Marriage Story”, despite the genericity of is title is a film that at all turns resists universality, instead bathing itself in specificity as much as it can.

The film’s opening supports this. Nicole emerges from darkness until her face illuminates the screen and we hear Charlie intoning a monologue, “What I love about Nicole…” Soon, they flip and we see a montage of him as we hear Nicole speak on “What I love about Charlie.” Soon, though, we realise this almost tritely banal see-sawing of how each partner sees the other isn’t emanating from spontaneity but occurs in a heavily mediated setting. The two are meeting a mediator, at the beginning of sorting out their divorce. The context changes what we’ve seen before. On one hand, it re-emphasises Baumbach’s interest int the specificity of these people. This is a film about Nicole and Charlie, not about Husbands and Wives. Even more significantly, though, it points to the centrality of the performativity as inherent to the film. They’re doing this “what I love bit” because they have to.

Nicole, in an early moment in New York, seems incredibly stoic as she speaks to Charlie – cool and calm in a way that negates any pain at this divorce. A moment later, as she bids him goodnight she breaks into a convulsive, but silent tears. The stoicism is the performance, not the fact. The schism between the perceived reality and the perceived truth, the uncertainty of where performance ends and the real begins, is one that persists through the film.

When Nicole flies to LA, her new producer suggests no matter how amicable this divorce may seem, she needs a lawyer. And so Nicole gets one. As she prepares for Charlie’s visit to the coast, she advises her sister, Cassie, on how best to serve him the divorce papers. She can’t, for legal reasons. “Just let me practice, I was never a good auditioner,” she demurs. “It’s not an audition!” Nicole insists. And it’s not, but it is a kind of a performance, isn’t it? Each moment seems to further complicate the limits of truth, the illusory nature of perception and these characters’ dependence on performance. In the middle of the film the lawyers for the couple pause a heated argument for lunch. Nora, Nicole’s lawyer, (played with sharp precision by an excellent Laura Dern) breaks the character of moving from playing incisive lawyer to perceptive fan as she heaps praise on Charlie. “I told Nicole, I LOVED your play”. He’s nonplussed. As are we. The moment is amusing for its startling nature, and at first glance seems to speak to Nora’s own slipperiness except Nora is not the only one performing. Bert, Charlie’s congenial lawyer, is also performing, telling Charlie a joke that’s clearly part of his performed charm, a way of relaxing rather than increasing the crisis. They’re all playing roles to each other and to themselves.

It made me think of how our daily interactions are filtered through illusion in key ways. And “Marriage Story” never gives us complete destruction of illusion. There’s no moment where illusions are completely shattered and truth emerges as supreme. Instead, Baumbach’s stylistic flair is a fade to black. In multiple moments of heightened tension, rather than pick at the scabs the film fades to black marking a passage of time. He leaves us to fil in the gaps, and it’s a wondrous show of trust in his audiences. The fades to black are not about Baumbach’s unwillingness to interrogate these characters. The film is conscious of the flaws of these people, for all the illusions of sympathy every bitten-word and sigh from Nicole seems to lay bare how Charlie is almost ambivalently uninterested in compromise. Instead, Baumbach deliberately builds a story with characters so specifically peculiar we begin to imagine their lives off-screen. In an early scene, one of the highpoints of the film, Nicole putters around Nora’s office, delivering a six-minute monologue detailing how the divorce came about. Johansson plays this excellently, undercutting her feelings, laughing to stop the tears, wanting to confess but self-conscious. Driver gets a similar long-take scene at the end. His is a song, Sondheim’s closing number from “Company,” where the protagonist, Bobby, lays bare his desire for real connection. Neither ever confesses the feelings those moments elicit to each other. They can’t. True honesty is only ever an illusion here. Like real life. We editorialise ourselves for the sake of the ones we love. It’s heart-breaking to watch because it’s also very true. Life is an act. That doesn’t make it any less real.