It is now well recognised that much of what we will become in adult life is determined by our experiences by ages 5 or 6, and last week, in discussing the effects of inequality and poverty, I suggested that this time span should be extended backwards to include what occurred in the womb. I intend to continue considering the myriad effects of inequality, but a Stabroek News editorial PISA and ‘maths mastery’ (SN:13/12/2017) mentioning that Singapore occupies the top spot in the 2018 International Student Assessment (PISA) caught my attention as being worthy of a side bar.

In 1966, the year Guyana became independent, it had a per capita income of US$344 and Singapore had one of US$567, but in 2018, the numbers were US$4,635 and US$64,582 respectively. According to an HSBC report, as a nation Singapore spends double the global average – some US$70,939 a year – on its children’s education (https://www.todayonline.com /singapore/singaporeans-spend-twice-global-average-childrens-local-education-hsbc) while Guyanese spend about US$1,000. In brief, this achievement holds lessons for Guyana, for when that country exited the ethnic cauldron of the Malaysian Federation in 1965, the per capita income of Malaysia was about US$325 – similar to Guyana’s – and like Guyana although by way of a complicated shared governance arrangement Malaysia has been able to ameliorate ethnic conflict, its per capita income of US$11,239 is still far below that of Singapore. Singapore left the Federation and became a state dominated by one ethnic group. Today it consists of 6 million people: 74.3%, Chinese, 13% Malays and 9% Indians. This context significantly affects national policy formulation, acceptance and implementation but this important aspect of Singapore’s success is not widely understood.

The SN editorial paraphrased a claim in the Economist magazine that schools often have less influence over examination results than most people think because cultural and social factors are as important. Furthermore, the magazine goes on to report that the data suggest there is not much of a relationship between financial outlay above US$50,000 per pupil annually and PISA results. The editorial quite rightly recognised that expenditure on education in Guyana is nowhere near that number, but then went on to suggest that to improve its results Guyana may want to consider reverting to the chalk and talk method of yore that has proven effective in the case of Singapore.

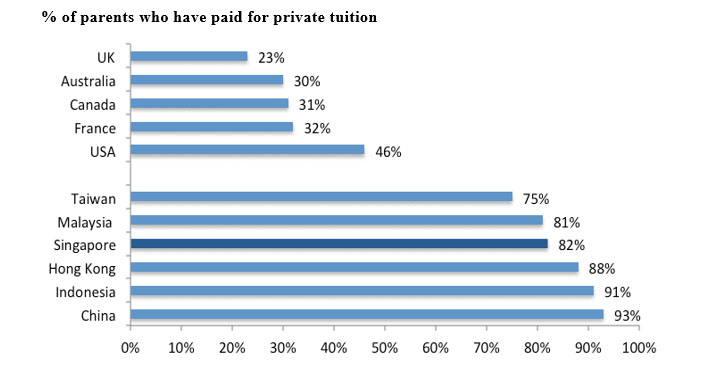

Whatever the added value of spending above US$50,000, Singapore spends almost double that sum and is surpassed only by Hong Kong (US$132,161) and the United Arab Emirates (US$99,378), and Hong Kong is also near the top (No. 4) of PISA. Teaching techniques are important but culture is as important and what the two states have in common is the Far Eastern attachment to private lessons and these two issues cannot be delinked if only because the latter brings a lot more parental interest and financial resources into the education process. ‘Some 82 per cent of parents said they are paying for private tuition or have done so in the past, and four out of five parents have started making plans for their child’s education even before the child begins primary school at age seven years’. Today, the government of Singapore itself spends about US$12,000 per child year on education, so the remainder of that sum must be going into private lessons that, like the model, also appear to be spreading.

(https://smiletutor.sg/an-overview-of-tuition-in-singapore/#part1.2).

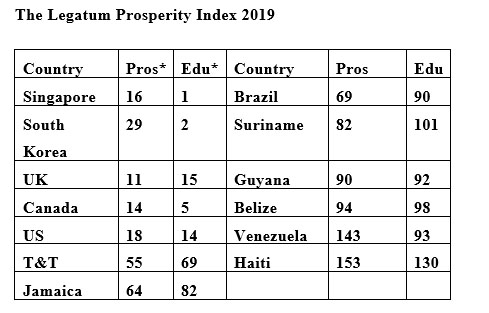

Although the matter had been under discussion in CARICOM since the early years of this century, the SN editorial noted that since Guyana is not a participant in the PISA one cannot properly compare it with the other participants. However, the Legatum Prosperity Index, which measures national prosperity based on institutions and economic and social wellbeing, does allow us to make some useful comparisons across the broad field of social development (https://www.prosperity.com/).

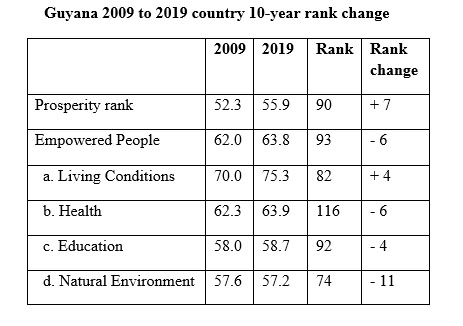

The 2019 Index considers 167 countries under a dozen broad headings: safety and security; personal freedom; governance; social capital; investment and entrepreneurial environments; market access; environmental quality; living conditions; health; education and the quality of the natural environment. It provides some interesting insights into conditions in Guyana, much of which, except for the heading ‘empowered people,’ under which is education our present focus, has not been particularly uncharitable to the regime. The following tables were constructed from that Index with the Guyanese reader in mind.

The Table shows that Singapore and South Korea, parts of the Far Eastern tradition, are respectively at numbers 16 and 26 in terms of global prosperity* but are over-performing (being at numbers 1 and 2) in terms of educational achievement*. On the other hand, most of the countries in the Caribbean except for the poorer ones beginning in the above table with Guyana, appear to be under-performing.

Be it from a very low level, empowering people – defined as creating better living conditions, health and education services and a better natural environment – is the only category in which outcomes went seriously awry over the ten year period. No one will deny that country-wide sanitation services have been a disaster and thus the 11 point drop in ranking is not surprising. In education, the overall 4 point decline represents respectively an 18, 9, 7 and 6 point drop in primary, secondary, adult and tertiary education, only somewhat salvaged by a 5 point rise in pre-primary education. It appears to me that unlike what may be possible in many other policy areas, education management requires a holistic approach and that this is not properly appreciated.