Auld Lang Syne

Should auld acquaintance be forgot,

and never brought to mind?

Should auld acquaintance be forgot,

and auld lang syne?

For auld lang syne, my jo,

for auld lang syne,

we’ll tak a cup o’ kindness yet,

for auld lang syne.

And surely ye’ll be your pint-stoup!

and surely I’ll be mine!

And we’ll tak a cup o’ kindness yet,

for auld lang syne.

We twa hae rin about the braes,

and pou’d the gowans fine;

But we’ve wander’d mony a weary fit,

sin’ auld lang syne.

We twa hae paidl’d in the burn,

frae morning sun till dine;

But seas between us braid hae roar’d

sin’ auld lang syne.

And there’s a hand, my trusty fiere!

and gie’s a hand o’ thine!

And we’ll tak’ a right gude-willie waught,

for auld lang syne.

For auld lang syne, my jo,

for auld lang syne,

we’ll tak a cup o’ kindness yet,

for auld lang syne.

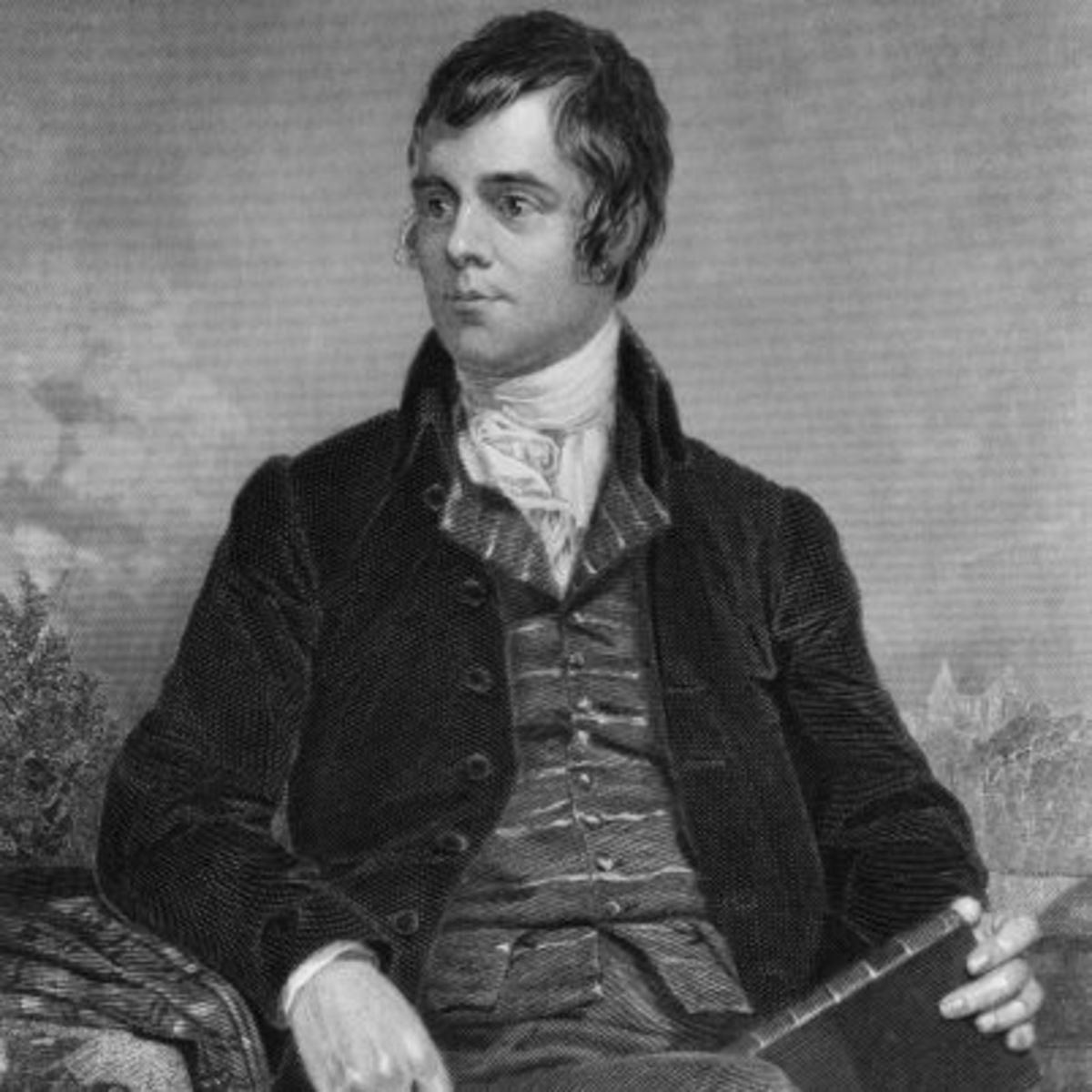

Robert Burns (1788)

At this point in the season, we revisit “Auld Lang Syne”, perhaps the most popular song in the world today. It continues to be fascinating how some of the best-known verses are equally among the most misunderstood or misinterpreted. “Auld Lang Syne” is among them.

In a few days’ time as we hasten towards the end of the year of Our Lord, two thousand, and nineteen (2019, Anno Domini), countless millions will be singing this song at the stroke of midnight on New Year’s Eve (called Old Year’s Night in some countries), Tuesday, December 31, 2019, which will also be the start of New Year’s Day, Wednesday, January 1, 2020. It will ring out on the radio and TV, played at parties, sung loudly wherever people are gathered in groups in private and public places, in several different languages in almost every corner of the globe.

It is a custom to sing it to ring out the old year and ring in the new. It is a part of the revelry, the merriment for everyone to sing in chorus, but it is also a kind of ritual to cast out the old year with all its cobwebs and sundry baggage, and welcome in the new one with all that is bright, fresh and promising.

That is the general tenor when people sing “Should auld acquaintance be forgot and never brought to mind/ Should auld acquaintance be forgot for auld lang syne”. It is common to several different cultures to see the turn of the year in this way. The month of January is so named because of Roman mythology. The month is named after the god Janus, who was two-faced, with one face looking back at the past year and the other looking forward to the new. January is thus named to reflect the spirit in which the song is sung on New Year’s Eve.

However, what the whole world is thinking when they sing “Auld Lang Syne” is largely a misinterpretation of the words and the spirit of the song, since that is really not what they mean. The verses that millions are singing are really from a poem by Robert Burns. Its meaning is almost the opposite of what people have in mind when they sing it at year-end. Even the idea of “ring out the old, ring in the new” comes from another poem, and can be taken as an illustration.

“Ring out the old, ring in the new,

Ring, happy bells, across the snow:

The year is going, let him go;

Ring out the false, ring in the true.”

That is taken from a poem called “Ring Out Wild Bells”, which is a part of a very long poem called “In Memoriam” by Victorian poet Alfred Lord Tennyson (1850). Tennyson’s poem is an elegy in memory of a friend and is indeed a poem in the tenor of starting anew after profound grief, and that is about rising from sorrow and embracing, instead, future happiness.

That is the context in which the popular New Year’s song is sung, but the context of Burns’ poem is quite different. It is mostly unknown to the multitudes that they are singing a poem by Robert Burns. The poet is not advocating the forgetting of the old, the casting out of the past – quite to the contrary, he is celebrating their value. To the question “should old acquaintance be forgot, and never brought to mind?” Burns’ answer is “No! Remember and value them, for the sake of friendship and human bonding; for the sake of humanity”.

Burns (1759 – 1796) was the national poet of Scotland, so called because he emerged as that country’s greatest lyricist. He also wrote most of his poems in the Scot language, rather than standard English. He is regarded as a Romantic poet – or rather a Pre-Romantic, since his life actually ended two years before the official launching of the Romantic movement (the publication of “Lyrical Ballads” by Wordsworth and Coleridge, 1798).

But Burns’ work and philosophy were in line with those of Romanticism. His ideology was rooted in the folk – he used their language, he wrote about them, his outlook was proletarian, or rather in empathy with the peasantry. He, himself, was a farmer. He believed in the ordinary language of the people, in the countryside – the landscape and nature abound in his poems, as he responded to the social and environmental impact of the onset of the industrial revolution. He researched in the field, collecting several examples of oral literature – folk songs and oral poems popular among the Scottish folk.

He wrote “Auld Lang Syne” in 1788. He sent it to the Scots Musical Museum with a note “The following song, an old song, of the olden times, and which has never been in print, nor even in manuscript until I took it down from an old man.” (various sources; including Wikipedia; Maurice Lindsay, 1996, The Burns Encyclopedia). He therefore composed it based on a song he collected in the field.

It is a love poem, a reunion, addressed to “my jo” (my dear), recreating the times they had together in the past. He recounts how they “run about the braes” and how “We twa hae paidl’d in the burn /Frae morning sun till dine (ie dinner time)”. They obviously had enjoyable times together. But they parted, as in “We wandered mony a weary fit” since those times, and “seas between us braid hae roar’d”. All of that indicates that they travelled different paths “since auld lang syne”; and a great deal of distance was put between them as they probably went to different countries (seas roared, distance developed, between them).

“Auld Lang Syne” is also a drinking song. There is a very long tradition of poems in praise of drink. These stretch from the Latin love songs of the Middle Ages in praise of wine and women (written by Roman Catholic priests and monks!), to the chutney lyrics of contemporary times celebrating rum. But there is a sub-theme in many of these, which go a little deeper to comment on the warmth and humane feeling that accompanies drink and its environment. There is camaraderie and understanding. William Blake expresses this in his ‘drinking poem’ “The Little Vagabond” in which the little boy, the persona in the poem, observes “Dear mother, dear mother, the church is cold / But the ale house is healthy and pleasant and warm”.

In “Auld Lang Syne” the protagonists meet in a pub. It is over drink that this feeling of reunion and friendship is expressed and ritualised. “And surely ye’ll be your pint-stoup!/And surely I’ll be mine” means “you will buy your pint (of beer or ale) and I’ll buy mine”. There is also reference to “a right gude-willie waught”, which is “a good-will draught” (of beer). Drink is the medium that is forging this new friendship and goodwill. But, as a good poet will always do, this is turned into something more profound. The poem says “we’ll tak a cup o kindness yet for auld lang syne”. A cup of kindness is expressive of the whole human bonding and value placed on the acquaintances and links of the past. A drink becomes “a cup of kindness”, a symbol of friendship, unity and goodwill.

After its publication this poem became associated with Hogmanay – the Scottish New Year’s Eve and ritual. A custom developed of groups singing the song while engaging in a hand-holding ritual. This was a symbol of unity and friendship which spread from Scotland to Ireland, Wales and England. The singing of the song at New Years was also carried by the people to wherever they migrated and soon found itself even further across the world. The hand-holding ritual, however, remained in Britain.

The depth of meaning did not migrate with the song, and more was also lost in the translation. The full meaning of the words “auld lang syne” was never known. There are several versions – “old long ago”; “old long since”; “long, long ago”; “days gone by”; “old times”; and “for old times’ sake” (various sources). People simply used it as a farewell song with little regard for “auld lang syne”.

But far from a superficial farewell, it carries “a tinge of nostalgia” and “is about preserving old friendships and looking back over events of the year” (ScotlandIsNow website). It advocates valuing the strong links of the past, and old acquaintances. It is indeed an appropriate poem/song for the New Year