![]() Sam Mendes’s “1917” arrives in local theatres this week as one of the last major films of 2019 to see a worldwide release. The film is a-day-in-the-life of two British soldiers during World War I who are tasked with getting a message of extreme importance to another battalion, stationed nine males away and flanked by enemy territory. Despite the relatively few films on WWI (WWII tends to be the one that gains most literary and cinematic interest), there’s a general familiarity that seems to follow stories of wars that leaves “1917” immediately trying to differentiate itself from its peers. What exactly could this film, or any film for that matter, tell us about the Great War that we don’t already know. But considering “1917” through those lenses as just as another war film feels unfair to what’s at work here, as even as the film is pulling from familiar stories of the war, it offers a cogent account of a specific tale of the war that is heightened by a technical flourish that is truly masterful.

Sam Mendes’s “1917” arrives in local theatres this week as one of the last major films of 2019 to see a worldwide release. The film is a-day-in-the-life of two British soldiers during World War I who are tasked with getting a message of extreme importance to another battalion, stationed nine males away and flanked by enemy territory. Despite the relatively few films on WWI (WWII tends to be the one that gains most literary and cinematic interest), there’s a general familiarity that seems to follow stories of wars that leaves “1917” immediately trying to differentiate itself from its peers. What exactly could this film, or any film for that matter, tell us about the Great War that we don’t already know. But considering “1917” through those lenses as just as another war film feels unfair to what’s at work here, as even as the film is pulling from familiar stories of the war, it offers a cogent account of a specific tale of the war that is heightened by a technical flourish that is truly masterful.

Of course, that technical flourish is the central argument in support of “1917”’s very existence, a film which emerges as a major contender in the current award season on the backs of it much publicised technical choice to shoot the film as if it all takes place in “one continuous shot”. It’s a detail that has led much of the conversation on the film, even though it’s quite obviously incorrect. There is a decisive break in the film roughly midway, where our protagonist blacks out, that decisively cuts the movement of time. Still, the one-shot (or two-shot) device is essential to what director Sam Mendes is working at here. Despite the largeness of the film’s title, its focus is quite small – it has no great interest in the larger arguments of the why and how of The Great War. It is, instead, a very specific rendering of the race against time to complete a specific task. So, in a trench in France, Lance Corporal Blake is asked to travel nine miles over territory that might (or might not) be filled with Germans to urgently tell Colonel Mackenzie that their planned attack is actually an ambush by the opposing forces. Blake chooses Schofield, a fellow corporal, as his companion and the two set off on a task that seems doomed. There’s little to the story beyond that. The film’s intent is to merely place us into the physical and mental headspace of these two young men, ambivalent about the war, disillusioned from the fighting but committed to completing this simple task.

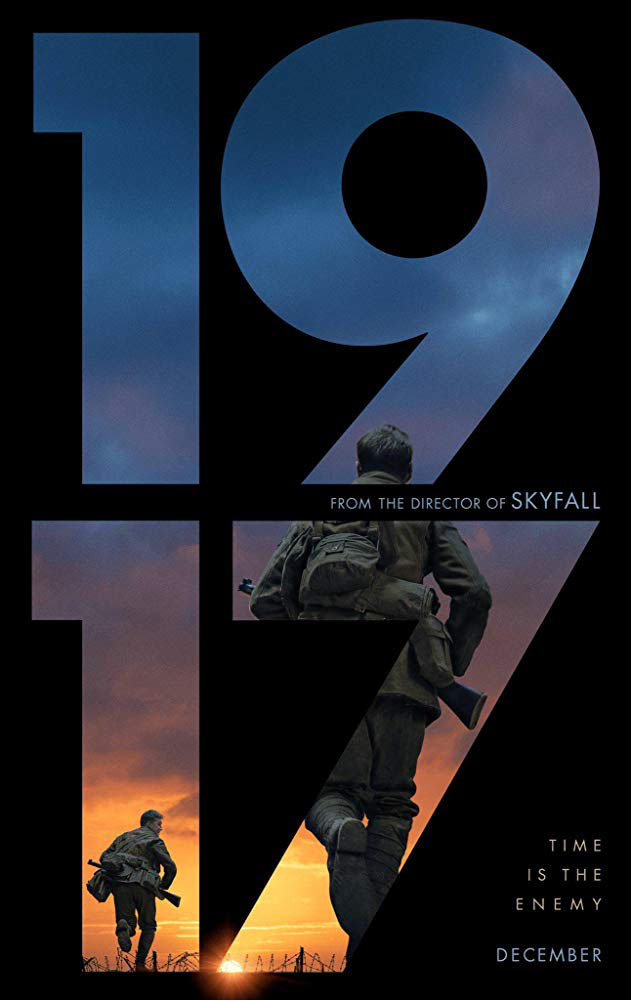

And, so, like any war film – but in particular, like any war film so focused on creating the physical environment of war, “1917” is a film that depends on its technical merits. There’s a sequence in “1917” where Corporal Schofield, played by George MacKay, tries to outrun some enemy soldiers. We see his figure rendered small against the backdrop of the midnight blue sky that’s temporarily yellow and then orange with the blaze of fire and then gunfire. It’s not necessarily the prettiest moment of the film, but the image has been seared into my brain because of how immediately dazzling it looks. (It’s so good, that a version of the shot is the featured on the film’s main poster.) And that moment, and the sequence it’s part of, delivers a key argument to the confluence of cinematography, sound design, music and production design that “1917” is depending on. Roger Deakins has maintained his reputation as one of the finest cinematographers in the business, so his work here isn’t surprising, but the way Thomas Newman’s anxious score, complements the shadows of the war ruins, and the isolation of Schofield in that moment represent the larger way that “1917” manages to harness a very specific kind of emotional headspace that commits to wearing the audience down.

In that way, it’s hard not to think about what Mendes is doing in “1917” against Christopher Nolan’s similar work in “Dunkirk,” which adopted the same kind of sensory overload to his account of the Second World War. “1917” is, however, of immediately less magnitude. Where Nolan sought to paint a larger picture of the entire Dunkirk crisis, Mendes’ day-the-life account is not about a truly momentous day for macro reasons, but just a

day in the lives of random people. But it is because of this that “1917” feels more impactful in its focus. The film’s technical prowess, and that one-shot device are hard to ignore, especially set against a script (Mendes cowrites with Krysty Wilson-Cairns) that’s serviceable but not especially nuanced. But, “1917” is more than the sum of the technical achievements at work here, and Mendes is doing more than being a caretaker for an excellent technical team.

1917” ignores larger questions about war for something more personal and humanistic. George MacKay is key to this. He’s carrying the weight of the film’s biggest work on his shoulders and, oftentimes, without speaking. It’s there, I suspect, one’s mileage might vary that is, in considering if “1917” has more to offer than a technical symphony. MacKay’s work digs deep even when the screenplay (by design) does not offer much. It’s not till the end of the film he tells us his first name. When the moment comes, he utters it as if he has almost forgotten he had one, emphasising in an incidental way the impersonal root of war.

I can definitely see the argument for how this kind of thing might be emotionally distancing but there’s a moment in the film where a soldier asks Schofield, “Am I dying?” and the slightest pause and furrowed brow that precedes his very matter-of-fact, “Yes. Yes, I think you are” feels incisive. The technical marvel that comes with “1917” is still the macro-side of it, the film’s very aesthetic and thematic interest is in compelling audiences to take part in the chaos of the war as a sensory experience – but if “1917” is a confirmation of Mendes’ style over substance inclinations, there’s enough substance here in the style that makes it one of the finer films of the year.

“1917” is currently playing at Caribbean Cinemas Guyana and MovieTowne Guyana.