The development of Guyanese literature may be studied in four periods: Pre-Colombian, before 1597; Colonial, from 1597 to the end of the nineteenth century; Modern, which includes pre-independence up to 1966; and the Post-Independence from 1966 to the present. Within these, there are sub-divisions.

The development of Guyanese literature may be studied in four periods: Pre-Colombian, before 1597; Colonial, from 1597 to the end of the nineteenth century; Modern, which includes pre-independence up to 1966; and the Post-Independence from 1966 to the present. Within these, there are sub-divisions.

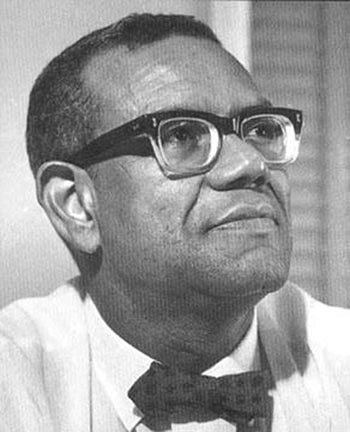

It can be said that Modern Guyanese drama began in the 1930s and includes pre and post-independence drama. In both literature and drama there is one writer whose work was mostly responsible for the founding of modern literature. While the poet and short-story writer Leo (Egbert Martin) was the founder of modern Guyanese literature in 1890, to a lesser extent, Norman Eustace (N E) Cameron did the same for modern Guyanese drama in 1931.

The literary journal Kyk-Over-Al was an invaluable companion to the development in these fields, particularly from 1945 up to independence. Indeed, Volume One of this magazine published poems, short stories and commentary, which gave a very good indication of the state of the literature at that time, particularly since the 1940s did the most to shape nationalism, identity and leading individual talents in the pre-independence period.

Editor A J Seymour exhibited his growing strengths as a poet and critic and published some of the leading and emerging poets of the period. There were notable names missing; C E J Ramcharitar Lalla, for instance, but it is possible to chart the progress of another, who became the constant North Star of Guyanese literature, Wilson Harris. At that time, he was among the best poets, but Kyk also featured significant short stories by Harris, which pointed futuristically to his fiction writing, which was to lead the world after 1960.

Kyk-Over-Al Issue 1, 1945, contained an important article on the state of drama in Guyana by Cameron himself. He is credited as the founder of the modern drama because before his interventions national drama was amorphous. There was no playwright of sufficient stature; not even Esme Cendrecourt, who Cameron described as the most prominent and productive playwright of the time. No strong corpus of local drama had emerged. Those of strong local quality were neither significant nor impactful. There was a pervading imitation of European drama and nothing that could merit any other label than colonial. This, of course, is with reference to the western written drama on the formal stage, because there existed formidable theatre in the folk traditions.

Cameron began to write plays after 1931 with a purpose, because he reported that he was unable to identify any Guyanese dramatists or theatre when asked to speak on the subject while he was in England. Furthermore, he recognised a level of self-contempt among local blacks, and found that there was no drama of the times that represented black people in a dignified manner or showed their qualities and glory. This was the period across the Caribbean when theatre as a whole (excluding the folk traditions) was still colonial, foreign and European, and local black characters had no prominent place. Where they did begin to appear, it was largely for humour or ridicule.

Cameron set out to write and produce plays that dignified black people. There are two things to note here: that this was not unlike the mission and efforts of Marcus Garvey in Jamaica around the same time; and the ethnic focus of the work.

A weakness of Cameron’s plays was that they went off to the continent of Africa, and to the Holy Bible for plots and heroes, rather than developing local Guyanese subjects. Moreover, they arose out of an African consciousness and represented only one part of the wave of cultural development of the 1930s and 40s. There was a wave of African cultural awareness and political development. At the same time there was a parallel wave of growing Indian consciousness following the stimulus provided by Joseph Ruhomon at the beginning of the twentieth century.

However, Cameron’s efforts at the time did put in place the production and publication of plays in British Guiana. There were cultural clubs, many of them named by Cameron in his Kyk-Over-Al article, which produced plays. (Clem Seecharran treats this subject with greater depth in India and The Shaping of the Indo-Guyanese Imagination and in Tiger In The Stars). But none of them produced noteworthy Guyanese playwrights or plays. A notable exception was Basil Balgobin, who developed as a playwright in the British Guiana Dramatic Society (BGDS), an exclusively Indian club.

In his coverage of drama in British Guiana in the Kyk article of 1945, Cameron made a number of interesting observations.

He quoted the report of an observer, that of all the colonies in the West Indies in the 1940s, British Guiana was the most active and productive in the production and performance of drama. Cameron then went on to reflect on this, listing an extremely prolific stage in BG, with several plays at a variety of venues by a range of groups, societies and clubs during the year 1944. He even moved back in time to the nineteenth century to cite other examples of the presence of theatre in the colony in those years.

There are significant points to be drawn from that. The list presented by Cameron was impressive. It represented what would have been the amateur theatre developed in the colonies after the wane of visiting professional companies from the UK and the USA. The listing of plays written and produced also went back several years before 1945 but did not identify major playwrights and major Guyanese plays. Many of the works were described as “sketches”, some were adaptations from European plays or excerpts from the classics.

Exceptions to those norms were Cendrecourt and Balgobin. On two occasions, Balgobin was named as having contributed plays to Guyanese drama. By Cameron’s account and in other sources there were two plays attributed to him, Savitri and Asra. But it was also clear that the BGDS focused on Indian plays, particular those by Rabindranath Tagore, and on Balgobin’s Asra, which was set in India.

Cameron also referred to theatre venues and quoted a nineteenth century source as mentioning a very well-appointed theatre building that staged plays but had not survived. He also mentioned the destruction by fire of the famous Assembly Rooms, and of plans to build theatres. He made references to the training of actors and practitioners in technical areas of theatre, which was lacking.

In the same period, there was impactful theatre in Jamaica. The most important illustration would be the founding of the modern theatrical form now known as the Jamaica Pantomime. The Little Theatre Movement (LTM) Jamaica Pantomime Musical is still strong today after having been developed in 1942 from a tradition of English pantomimes performed annually in Jamaica by expatriate residents. That was also the formation of the LTM itself, a consistent producer of plays in Jamaica. Additionally, during that period there were dramatisations of novels such as The White Witch of Rose Hall. This was the exhibition of indigenous material on the Jamaican stage that must have represented significant theatre at the time.

In Guyana, the several separate drama groups and their many performances in different places did lead to important and relevant developments. These continued into the 1950s, because some of these interests came together to form the Theatre Guild by the end of the decade of the 50s. The hall of the Bishops’ High School, mentioned by Cameron, was a central place and one of the theatre performance venues that led to the eventual formation of the Theatre Guild that was developing by 1957.

The Theatre Guild Playhouse in Kingston was in existence by 1962, the fulfilment of one of the goals Cameron referred to in 1945. Another goal was the training of dramatists. Cameron mentioned playwriting and playmaking. These, too, became a reality when the Theatre Guild became a training house for many of the leading dramatists of the Caribbean. Some moved on to other countries including Trinidad and Tobago, Barbados, Jamaica and the Cayman Islands. Institutions to which they went included Derek Walcott’s Trinidad Theatre Workshop, the University of the West Indies, Cave Hill and Barbados’ Stage One Theatre, the Cultural Foundation in the Cayman Islands and the Jamaica Cultural Training Centre (Edna Manley College of the Visual and Performing Arts).

Cameron referred to the observation that BG was most prolific among West Indian colonies in 1944. Today, only Jamaica has a busier, more active schedule of theatre productions on stage than Guyana. In terms of state-of-the-art equipment and technical quality, other major theatre communities like Trinidad and Barbados might outstrip Guyana, but they fall behind in terms of the frequency of theatre productions.