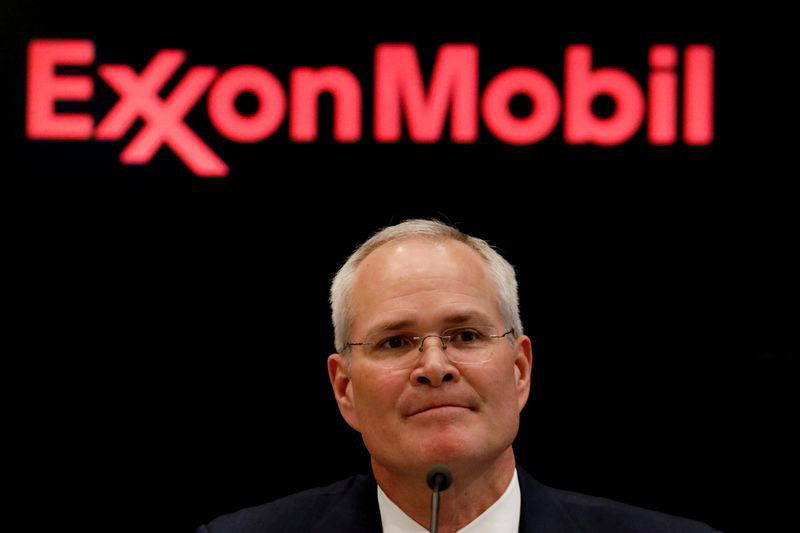

HOUSTON (Reuters) – At Exxon Mobil Corp, CEO Darren Woods’ plan to revive earnings at the largest U.S. oil and gas company is being sidetracked by the two businesses he knows best: chemicals and refining.

Another year of poor profit could require Exxon to re-evaluate its bold spending plans or weaken its ability to weather the next oil-price downturn, say oil analysts. Exxon already must borrow or sell assets to help cover shareholder dividends.

The world’s biggest publicly traded oil firm after Saudi Arabian Oil Co, Exxon was long considered one of the best-managed majors and most capable of coping with volatile prices due to its size.

Those advantages have slipped in recent years, however, with the drop in once-steady earnings from chemicals. Its total shareholder returns of negative 13% in the five years through this month compare with a 25% gain at Chevron Corp and 82% at BP Plc, according to Refinitiv.

Two years ago, CEO Woods promised to restore flagging earnings by heavily investing in operations even as rivals cut spending. The plan to crank up chemicals, refining and increase oil output pushes capital expenditures to as much as $35 billion this year, up from $19 billion in 2016, the year before Woods took over as CEO after running Exxon’s refining and chemical businesses.

Last March, he forecast potential earnings could hit $25 billion this year and nearly $31 billion in 2021, close to the $32.5 billion it earned in 2014 before the oil-price collapse.

The hoped-for payoff, however, has run headlong into a global chemicals glut, tariffs on U.S. exports to China, and lower margins in fuels. Exxon’s refining profit last year fell on equipment outages.

The company declined to comment ahead of quarterly earnings, expected on Friday.

On Monday, Exxon shares traded under $65 – close to their level of 10 years ago.

The company recently telegraphed weak fourth-quarter results because of chemicals and refining businesses. Wall Street cut profit forecasts through 2021 on the sour outlook for both. Exxon “seems to be tracking way behind their own expectations,” said Evercore ISI analyst Doug Terreson, who slashed his quarterly forecast by a third, to 55 cents a share.

In chemicals, Woods expanded the company’s output of polyethylene, a business where it has 9% of global production capacity, to benefit from demand for plastic bags, food packaging and consumer goods. Output rose last summer at the depth of the U.S.-China trade dispute, and industry margins for a key polyethylene fell 30% compared with levels between 2016 and 2018, said James Wilson, analyst at pricing provider ICIS.

“The industry ended up overbuilding,” said Pavel Molchanov, an analyst with investment firm Raymond James. “Exxon, of course, is among the companies that led that build-out.”

In refining, outages and higher maintenance costs at Exxon refineries in the United States, Canada and Saudi Arabia hurt profit, according to regulatory filings.

Crude oil prices and slack global demand from the trade dispute are squeezing profit across the industry, said Garfield Miller, chief executive at Aegis Energy Advisors.

This month, an Exxon regulatory filing implied a loss in chemicals of about $200 million for the fourth quarter, and refining earnings of just $400 million.

In contrast, chemicals and refining delivered $7 billion to $11 billion annually for Exxon between 2013 and 2018. In the first nine months of last year, the combined profit was $2.37 billion. Exxon’s regulatory filing indicates 2019 earnings for the two at about $2.52 billion, the lowest in at least a decade.

Woods has halted the company’s oil output declines by ramping up in shale. Oil volume has risen year-over-year for five straight quarters, reversing annual declines between 2016 and 2018.

Ending the trade dispute represents the biggest challenge. Global demand for the plastic resins and pellets that Exxon makes is rising, said Marc Levine, chief executive of Plantgistix, which provides logistics for U.S. plastic manufacturers.

“This is the first time in my lifetime and in the plastics industry’s lifetime where we make plastics resin for export,” said Levine.

China in 2018 placed an additional 25% tariff on U.S. polyethylene imports, a move that helped send North American margins to the lowest levels since 2011, said Joel Morales, a polymers analyst at consultancy IHS Markit.

“Imagine having a lot of something and your biggest, easiest consumer you can’t do business with,” Morales said.

The January U.S.-China agreement does not remove Chinese or U.S. tariffs on chemicals, plastics or oil.

Exxon has ramped up asset sales, aiming to collect $15 billion by next year to balance spending. So far, results have been tepid. It expects to receive about $3.6 billion from selling Norwegian oil and gas production assets.

Weak demand for those assets comes as rivals have written off the value of their own properties. BP, Chevron, Equinor, Repsol SA and Royal Dutch Shell Plc last year cut a total of $22 billion primarily on U.S. assets due to sharply lower gas prices. Exxon has not signaled whether it expects any writedowns.