Initially, it began in late December, 2004, when torrential rains resulted in serious flooding along Guyana’s coastal region.

Some might say it was a sign of what was to come.

In early January, 2005, though there were still reports that some areas on the coast, including Ogle and Sophia were still flooded as a result of the incessant rainfall which began on Christmas Eve, 2004, to many, it seemed like the worst was over.

However, on January 15th, fifteen years ago, hundreds of persons in Georgetown woke up to floodwaters seeping into their homes, destroying electrical appliance and other household items.

“We really thought it was over,” 55-year-old Janice Fraser of South Ruimveldt recalled during an interview with Stabroek News earlier this month.

The reason she thought it was over, Fraser said, was because, “the severe flooding had already occurred and it couldn’t get any worse.”

“The [2004] flood was already so bad we didn’t think it could get more bad so when the rain ease down lil bit, we was like, alright the worse done,” she recounted, before adding that when the rain again started pouring non-stop on January 14th, 2005, she initially brushed it aside never once thinking that soon she would have to leave her home for one of the high school buildings in Georgetown.

The severe flooding reached its peak around January 17th, 2005, when a high lunar tide and unusually heavy rains combined to inundate areas occupied by nearly half the country’s population. West Dem-erara/ Essequibo Islands (Region 3), Dem-erara/ Mahaica (Region 4) and Mahaica/West Berbice (Region 5) were the most severely affected. As a result, the government declared those regions disaster areas. Overnight, in the city and in coastal communities, thousands were forced to flee their homes, navigating flooded streets in cars and old refrigerator boxes, which were converted to boats. Some took shelter in multi-storey hotels, where rooms were all booked in a matter of hours and close to 5,000 people stayed in temporary shelters.

Meanwhile, others remained trapped in the upper flats of their homes, dependent on the daily delivery of food and water by non-governmental organisations and government agencies alike. Many areas were accessible only by boat and persons were forced to traverse through waist-high water in order to get to food and medicine supplies. Given the situation, the then president Bharrat Jagdeo encouraged persons to take credit from shops and promised to pay the shop owners when floodwaters had receded. However, reports indicated that some shop owners were unwilling to give persons credit fearing that they wouldn’t be paid.

Lull

After January 19th, there was lull in rainfall, which allowed a significant amount of water to drain off higher grounds but many areas were still flooded. Within days, floodwaters had overflowed canals, many of which were clogged with silt and garbage. Kokers were jammed and inoperable, resulting in floodwaters, which by this time had overwhelmed drinking and wastewater management systems, being unable to escape.

Floodwaters continued to rise insidiously until its depth reportedly reached a level of five feet in some places. Livestock and other animals were killed by the rising waters even as sewage contaminated floodwaters. Farmlands across the coastland were drenched.

Fishermen brought their boats out of the sea to assist with transporting families to and from shops and shelters. Others navigated their way through the floodwaters in old refrigerators or in anything that could serve as a boat while others simply walked through the floodwaters in order to get food.

With food supplies running low, vendors and shopkeepers increased the prices on food supplies. Rains continued until the first week of February 2005. Floodwaters were receding at a slow pace and damage to low lying infrastructure, agriculture production and livelihood were beginning to show.

The coastal stretch between Georgetown and Mahaica on the East Coast Demerara bore the brunt of the disaster.

Water levels were high and continued to rise as the water ran off from higher ground while there was overtopping of the East Demerara Water Conservancy (EDWC). Hundreds of families, like many others in the city, were forced to evacuate their homes and take shelter in multi-storey school buildings.

According to Priya Ramroop, a resident of Lusignan, on the fateful morning of January 15th, 2005, she had placed a barrel underneath the roof to catch rain water but only five minutes had passed when suddenly there was “black water” everywhere and it was rapidly rising. “There was black water all over and the barrel not even half-full yet,” she recalled. Ramroop said she quickly alerted her mother, who lives in the bottom flat of their two-storey home and they quickly tried to move whatever they could upstairs.

Ramroop attributed the flooding to the overtopping of the East Demerara Water Conservancy (EDWC) and the canals making up the irrigation network. “It looked like we were living in the sea, all around was water,” she recalled. Trapped in their upper flat of her home, she said, her family depended on rations that were being distributed to affected areas. Meanwhile, their livestock were suffering so they braved the rains and floodwater to move them to higher ground, where they were eventually stolen after being left unguarded.

However, the hardest part for the family during that time was the drowning of a relative. Ramroop disclosed that her nephew, who was just a year old, somehow found his way from the upper flat to the bottom flat of her sister-in-law’s home and drowned in the rising water. “She [the sister-in-law] say she just turned to make some food and when she turn back he disappear. She went straight downstairs and found him already dead. He didn’t make no sound or anything,” Ramroop tearfully disclosed.

Man-made disaster

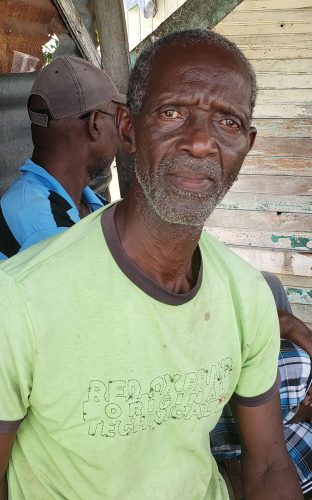

A resident of Buxton, Moses Glen, 39, said that sometime after it started raining, the conservancy overtopped. He said, for him, the worst part was seeing dead cows, horses, chickens and ducks floating around the village. He further revealed that he and his family were among those that evacuated their homes and stayed on the line-top. “It was really, really bad ‘cause we had to depend on Food for the Poor and the government to bring thing for we because we couldn’t work or anything,” he said.

Glen added that it took at least six months for things to return to normal at his home and farm especially since he had no money to buy detergents to clean his house. However, it was replanting and waiting for his crops to mature that contributed significantly to the sloth in getting back on his feet.

Another farmer, John (only name given) of Golden Grove, 55, made similar statements saying that since all his crops were destroyed during the flood, it was hard to get back on his feet because he had no money. He said they were promised seeds and other materials that would help them get back on their feet by the government but they didn’t receive anything and had to struggle. “It was long, long ago. All I remember was that we had to rush out and move out to higher ground. We couldn’t do much for the things, the livestock and plants. For days we stayed on plots of land that were dry and watch as these dead animals like dog, chicken, cows float around,” he recalled. Nevertheless, John said that after three months he had started planting his crops.

Vibert Simon, 60, also a farmer of Golden Grove said that during the flood he lost over 200 pigeon peas plants. He said he was visited by government officials who told him that they would compensate him for his losses. They never came, he added. “I lose a lot of pigeon peas really and we were living on pigeon peas, we use to depend on it for a little bit of money but nobody never come back and say nothing. In addition, he said, he was among the persons that had to move out of his home when the flooding began. Afterwards Simon added it was very difficult to get back on his feet; he received no assistance, the land was soaked and he couldn’t get anything back into the earth.

Meanwhile, Gary Kellman, 50, a resident of Annandale said that a couple of days after it first began raining, he moved his family to Georgetown. As a result, his family was not affected as some families had been. “We followed the information that the Ministry of Health had put out as it relates to the leptospirosis so that we wouldn’t catch the disease. Because we had to traverse, we had to be in the water some time or another, we had to make contact with the water so, unless we had boats, we tried as much as possible to not make contact with the water. Here, the water was four feet [deep] and we had losses but they were minimum,” he said.

Felicia Singh, 37, who lives in Better Hope, said that ‘the great flood’ for her was something that she would never forget but she is thankful that her family and many other families made it through. At that time, she said, her eldest was one-year-old so that made it especially challenging. “It look like a big ocean, my brother-in-law had an old fridge and they come and share tablets (medicine) to prevent infection. He carried people who want to go out. He never charged a fare and people would share something and we depended on the food that they were sharing. What make it flood was the dam that break. But since then people does try to keep trenches and so clean here,” she stated.

The Great Flood was Guyana’s worst natural disaster in decades, and was compared with the flooding of 1934 and 1888, but according to some, it was also a “man-made disaster.”

Sunil Singh, 56, said that since the area began flooding in 2004, persons started talking about the years-old drainage system that had fallen into disrepair. “It was a man-made disaster. For many, many years, they totally ignored the canals or trenches and kokers. People throwing their garbage all over the place, blocking up the systems that can drain off water and then they wondering why that happened to us, some of them kokers didn’t open for years,” he stated.

His friend, Jagdesh (only name given) of Den Amstel, West Coast Demerara, agreed with him and added that even now, people are still throwing their garbage in the trenches. “Like they gone never learn and if it happen again they will blame it on rain or sea or tide but if they don’t keep the irrigation systems clean how they expect floodwaters to drain?” he asked. He further added that during the spring tide last year, people were already complaining about flooding. “But if you di come and look around you woulda see garbage everywhere floating. They just don’t learn,” he said, shaking his head.

A total of 34 lives were lost during the flooding. Seven persons died by downing and the rest were attributed to illness arising from the flood. Among the seven who died as a result of drowning were Nicola Alleyne, who was a resident of Friendship and who died after she left home to locate some coconuts; Neezam Ali Dookie and Latchman Muguma, both of whom were found dead by the police; Andy Ramroop, the nephew of Priya Ramroop; and Chatterpaul Persaud, an epileptic, whose body was found floating not far from his home in Lusignan.