BOSTON/LONDON (Reuters) – Climate change commitments by banks, pension funds and asset managers face their first major test as markets reel from the twin shocks of coronavirus and a sliding oil price.

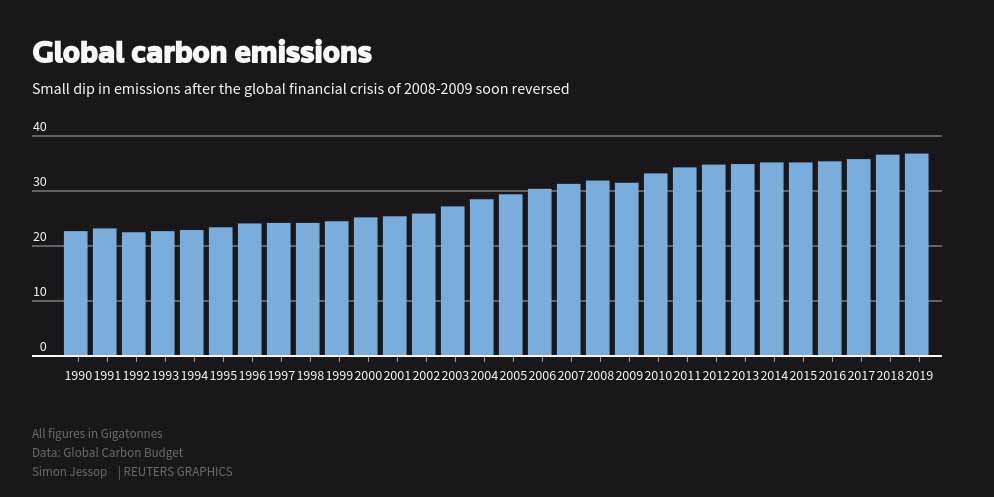

The challenge looks formidable. When the 2008 financial crisis tipped the world into recession, carbon emissions fell. But as economies grew again, governments proved unable to halt an emissions rebound.

The issue now is that at a crucial moment for international negotiations, the latest global economic blow could put paid to costly ideas for slowing climate change from political leaders and the private sector alike.

“When things are more difficult then people are really going to be focused on financial performance,” Hester Peirce, a Republican member of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) said Monday as world markets dived.

This time around, money managers interviewed by Reuters say a growing recognition of the prospect of massive disruption, underscored by Australia’s bushfires, has permanently shifted the dial and put environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues front and center.

“People look at ESG as a luxury and when recession hits it gets thrown out of the window,” said Michael Lewis, who heads research into environmental issues at German asset manager DWS.

“There’s still going to be significant pressure on policymakers not to take their eye off the ball, because of the financial materiality of climate change,” he added.

CLIMATE OF FEAR

The initial stages of the epidemic in China have already had a dramatic impact on the world’s biggest emitter of carbon dioxide, as Beijing locked down whole areas, shutting down factories and preventing travel.

Finland’s Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air says Chinese CO2 emissions fell by a quarter, or an estimated 200 million tonnes in the four weeks to March 1.

Satellite data also showed a sharp fall in Chinese emissions of nitrogen dioxide, a noxious gas emitted by power plants, cars and factories, starting in Wuhan and then spreading over other cities, including the capital, noticeable over a fortnight in mid-February.

“There is evidence that the change is at least partly related to the economic slowdown following the outbreak of coronavirus,” NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center said in a report.

But China has since began to resume business as usual and globally scientists say it is too early to estimate what the coronavirus outbreak’s economic impact may mean for emissions.

In 2009, global carbon emissions fell to 31.5 gigatons from 32 gigatons, the Global Carbon Project said. But as the global economy recovered, emissions jumped to 33.2 Gt in 2010 and to a projected 36.8 Gt in 2019, a record high.

The recession’s impact in the United States was particularly marked, with CO2 emissions falling 10% between 2007-2009, due to factors including less consumption of goods and services, a paper here published by science journal Nature Communications said.

Steve Davis, an associate professor at the University of California at Irvine and one of the paper’s authors, said the growing U.S. usage of natural gas helped suppress the rebound.

“The conclusion that the Great Recession helped decrease emissions is still true,” he said. “But that’s not the way we want to win the war on climate change.”

FAREWELL FOSSIL FUELS?

Coronavirus and the oil price fall come at a fraught time for international talks to avoid catastrophic global warming.

Observers fear governments will delay making ambitious pledges at a make-or-break U.N. summit in Glasgow in November.

“A recession is likely to complicate the politics of environmental policy, as it will drop in priority relative to the economy,” Ruben Lubowski, chief natural resource economist at the Environmental Defense Fund, a Washington, D.C. advocacy group, said.

Others see the drop in oil prices as an opportunity to impose more extensive carbon taxes.

“The money raised can be used to support fossil fuel workers and retool the economy,” said Kingsmill Bond, energy strategist at financial think-tank Carbon Tracker.

The price plunge in oil triggered by a Saudi-Russia price war could also affect the shift away from carbon.

With shares in oil majors hit hard this week, some investors question the wisdom of new oil and gas exploration, climate issues aside.

At the same time, low oil and gas prices could reduce incentives for big emitters such as the European Union, Japan, China and India to wean themselves off fossil fuels.

“A lower oil price will stall the green revolution in the world,” Michel Salden, senior portfolio manager at Vontobel Asset Management, said.

But rapid renewable energy cost falls could give decarbonisation more momentum than in past downturns.

Steve Young, chief financial officer of Duke Energy Corp, a major U.S. electric utility, told Reuters the coronavirus so far does not seem to affect progress toward its goal of reducing its carbon footprint by 50% by 2030 and reaching net zero carbon emissions by 2050.

Investors will also watch if any government stimulus packages aim to accelerate decarbonisation or simply encourage more high-emitting projects.

Changed social attitudes could make it hard for politicians to dismiss climate concerns, Keith Skeoch, chief executive of Standard Life Aberdeen, said. But low oil prices will have some influence.

“Cheap oil and cheap petrol probably does make (it), from a consumer’s perspective, potentially a little bit more difficult to decarbonise,” Skeoch said.