MUMBAI/CHENNAI, (Thomson Reuters Foundation) – People suspected of having the coronavirus in India have received hand stamps and are being tracked using their mobile phones and personal data to help enforce quarantines, raising concerns about privacy and mass surveillance.

The outbreak, termed COVID-19, has infected more than 234,000 people worldwide and killed nearly 10,000, according to a Reuters tally.

In India more than 200 people have been infected and four have died, with officials reporting multiple cases of people fleeing from quarantine.

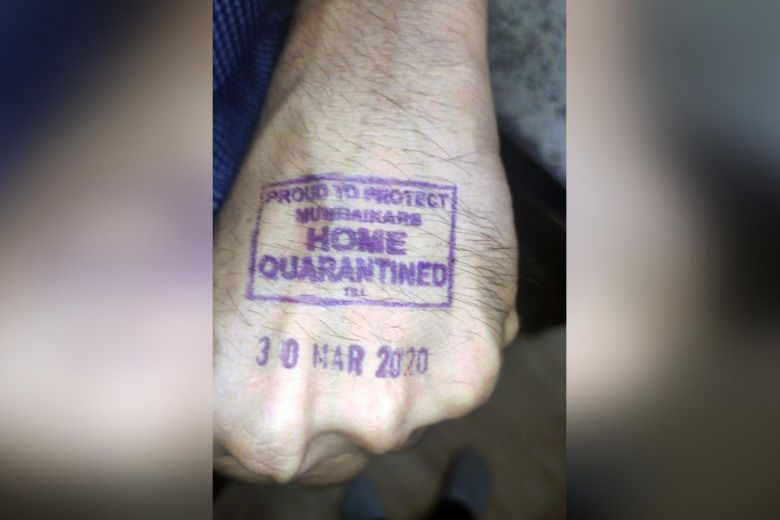

In response, the western state of Maharashtra and southern Karnataka state this week began using indelible ink to stamp people arriving at airports.

The hand stamps include the date that a person must remain under home quarantine, and states that those marked are “proud to protect” their fellow citizens.

“When I first heard of the stamping in Mumbai, I thought it was fake news,” said Supreme Court lawyer N S Nappinai, an expert in data privacy legislation.

“I understand the concern but where does one draw the line? Should fundamental rights be suspended in an emergency like this?”

The coronavirus outbreak has enabled authorities from China to Russia to increase surveillance, with the risk that these measures will persist even after the situation eases.

Technology is being used across Asia to track and help contain the epidemic.

In India, government officials are also pulling out citizen and reservation data from airlines and the railways to track suspected infections.

“We found people who were stamped and were travelling. They had signed a self-declaration that they will not travel because they could be carriers of coronavirus,” said Archana Valzade, under secretary in Maharashtra’s health department.

“It is their duty as well to stop the infection. Stamping is essential and very useful to reduce the spread,” she told the Thomson Reuters Foundation, adding no one has raised objections so far.

In southern Kerala state, authorities have used telephone call records, CCTV footage, and mobile phone GPS systems to track down primary and secondary contacts of coronavirus patients. Officials also published detailed time and date maps of the movement of people who tested positive.

“People have been jumping quarantine and it has been a challenge to track them,” said Amar Fettle, who is heading the coronavirus control team in Kerala.

“But we have formed hundreds of squads, including policemen to track and ensure people follow the norms.”

As more COVID-19 cases are reported in India, Prime Minister Narendra Modi on Thursday urged citizens to stay home and follow government instructions.

Modi’s appeal came just days after several news outlets reported that stamped people had broken self-quarantine rules.

In Mumbai, travellers with a history of having visited coronavirus-impacted countries were asked to get off a train, health officials in Maharashtra said.

In the eastern city of Kolkata, a bureaucrat’s son met with friends on his return from a visit to Britain and had to be forced to be admitted in the hospital where he tested positive.

“As a doctor who has worked in the public health service and in the community, I find people are not realising the seriousness of the pandemic,” said physician Armida Fernandez, former head of one of Mumbai’s biggest municipal hospitals.

“Knowing the situation of public health in India and that we are dealing with 1.3 billion people … I am for the steps the government is taking,” she said.

MUMBAI/CHENNAI, (Thomson Reuters Foundation) – People suspected of having the coronavirus in India have received hand stamps and are being tracked using their mobile phones and personal data to help enforce quarantines, raising concerns about privacy and mass surveillance.

The outbreak, termed COVID-19, has infected more than 234,000 people worldwide and killed nearly 10,000, according to a Reuters tally.

In India more than 200 people have been infected and four have died, with officials reporting multiple cases of people fleeing from quarantine.

In response, the western state of Maharashtra and southern Karnataka state this week began using indelible ink to stamp people arriving at airports.

The hand stamps include the date that a person must remain under home quarantine, and states that those marked are “proud to protect” their fellow citizens.

“When I first heard of the stamping in Mumbai, I thought it was fake news,” said Supreme Court lawyer N S Nappinai, an expert in data privacy legislation.

“I understand the concern but where does one draw the line? Should fundamental rights be suspended in an emergency like this?”

The coronavirus outbreak has enabled authorities from China to Russia to increase surveillance, with the risk that these measures will persist even after the situation eases.

Technology is being used across Asia to track and help contain the epidemic.

In India, government officials are also pulling out citizen and reservation data from airlines and the railways to track suspected infections.

“We found people who were stamped and were travelling. They had signed a self-declaration that they will not travel because they could be carriers of coronavirus,” said Archana Valzade, under secretary in Maharashtra’s health department.

“It is their duty as well to stop the infection. Stamping is essential and very useful to reduce the spread,” she told the Thomson Reuters Foundation, adding no one has raised objections so far.

In southern Kerala state, authorities have used telephone call records, CCTV footage, and mobile phone GPS systems to track down primary and secondary contacts of coronavirus patients. Officials also published detailed time and date maps of the movement of people who tested positive.

“People have been jumping quarantine and it has been a challenge to track them,” said Amar Fettle, who is heading the coronavirus control team in Kerala.

“But we have formed hundreds of squads, including policemen to track and ensure people follow the norms.”

As more COVID-19 cases are reported in India, Prime Minister Narendra Modi on Thursday urged citizens to stay home and follow government instructions.

Modi’s appeal came just days after several news outlets reported that stamped people had broken self-quarantine rules.

In Mumbai, travellers with a history of having visited coronavirus-impacted countries were asked to get off a train, health officials in Maharashtra said.

In the eastern city of Kolkata, a bureaucrat’s son met with friends on his return from a visit to Britain and had to be forced to be admitted in the hospital where he tested positive.

“As a doctor who has worked in the public health service and in the community, I find people are not realising the seriousness of the pandemic,” said physician Armida Fernandez, former head of one of Mumbai’s biggest municipal hospitals.

“Knowing the situation of public health in India and that we are dealing with 1.3 billion people … I am for the steps the government is taking,” she said.