World literature has never failed to provide insights into politics and the human condition. Following suit, Guyanese fiction, poetry and drama have variously addressed its politics at different stages in its history – whether it is the rising trends of nationalism in the pre-independence era or the rising tides of a shocking and scandalous determination to rig the elections on the independent nation’s fiftieth year as a republic.

World literature has never failed to provide insights into politics and the human condition. Following suit, Guyanese fiction, poetry and drama have variously addressed its politics at different stages in its history – whether it is the rising trends of nationalism in the pre-independence era or the rising tides of a shocking and scandalous determination to rig the elections on the independent nation’s fiftieth year as a republic.

Several of the best writers in the country have been reflecting the politics over these past hundred years. In the earlier colonial years, as soon as the fledgling poetry began to find its identity, patriotic sentiments and a more enduring sense of nationalism were striking factors in the treatment of politics. It took much longer and several decades of social realism before the protest literature addressing the politics of the 1970s and eighties emerged in the 1990s.

Today, when analysis, first-hand reports, eyewitness accounts and observations from all corners of the local, Carib-bean and international community have with one voice been condemning illicit declarations of unlawful vote counts, one can still turn with interest to the literature for some sane resolution in the denouement of political cataclysm. These things are unfolding before our very eyes, but one is still able to find treatment of local contemporary politics.

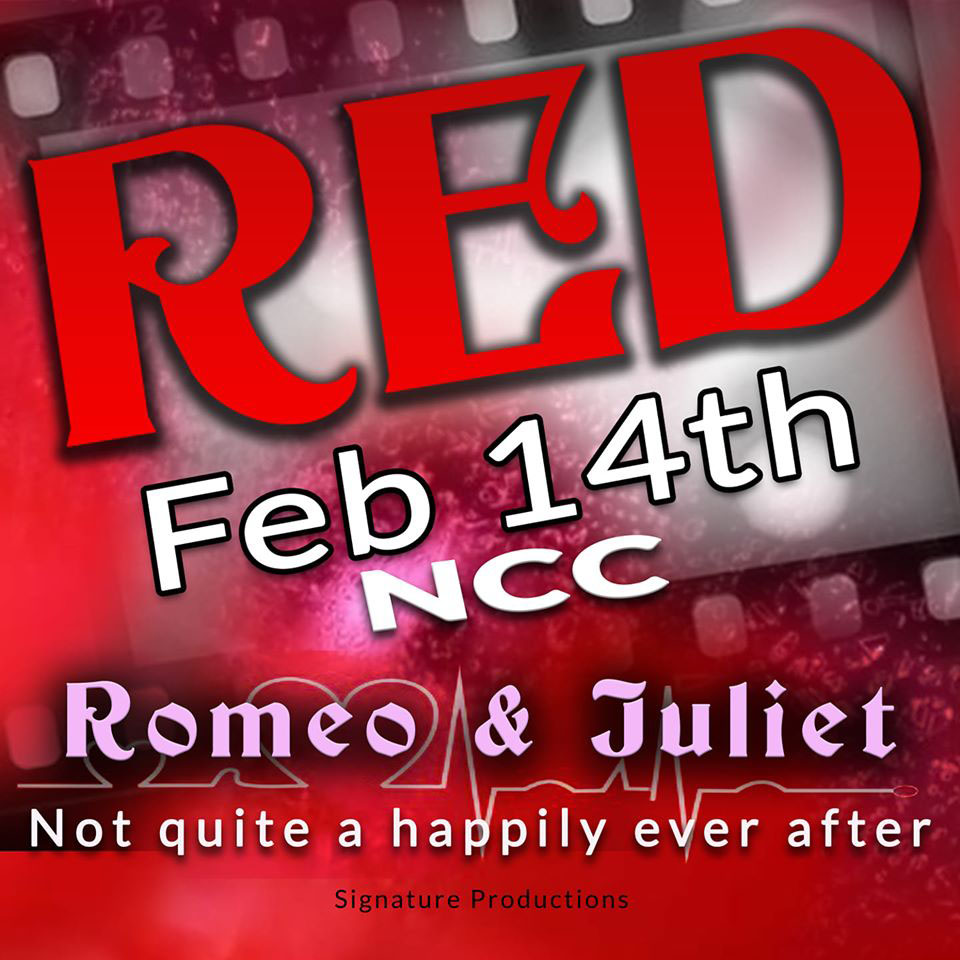

This can be found in drama. Two productions of political satire have already lit up the stage. Link Show 35 and a production called Red which featured a parody of Romeo and Juliet were both performed in February. Their timing and focus were pre-election, so they were laughing at the pre-ballot campaigning. But in the scope of their lampooning, it was impossible to avoid some reflection on the farce that was to follow the close of polls on March 2.

Red parodied the tragedy of “two households, both alike in dignity” and borrowed from Shakespeare to tackle the pitched battle between two tarnished political parties and the comedy of errors that the clash between them produced. There was an obvious attempt afoot to steal the state, but the larger tragedy was the tarnish that engulfed the whole society. The sullied act of one party is a reflection that “something is rotten in the state (of Denmark)”.

This was a production whose main part was a play composed by diverse hands, including award winning comedienne and actress Leza Singh, Maria Benschop and others. It was directed by Singh and produced by the same company responsible for “Uncensored” and “Nothing To Laugh About,” which are the leading events on the popular stage. It had as many good ideas as perplexing ones, causing the audience to wonder whether it was a drama or a variety show. It was never clear whether the several appearances of a solo singer and later an act by a team of break dancers were acts in their own right, or fillers to occupy time while they changed the set. They certainly contributed nothing to the dramatic play.

What should be remembered is that the production was staged on Valentine’s Day and was undoubtedly an act of carpe diem. It was a love story for the romantic theme of the day, and secondly, to also cash in on the general elections for which campaigning was at the time at fever pitch.

The main event, though, was the play, which was a parody – a take-off of Shakespeare’s evergreen theme about star-crossed lovers from antagonistic backgrounds, which repeated copies and adaptations over the years have not managed to make stale. This version was based on the war between Guyana’s two main political parties – the PPP/C against the APNU/AFC. It further contrived a love affair between the daughter of the leader of the Indian faction and the son of the leader of his black archenemy. Thereafter, it made fun of the hilarious situations arising therefrom and exploited several possibilities for political and social satire.

Among the good ideas was the use of a narrator. This is always an interesting theatrical ploy, which started out quite well in this drama, played to suit by Nirmala Narine. But it was not sustained in the writing of the script and squandered opportunities for real humour. She did indeed score a few telling blows for dramatic parody and laughter but was not used enough and as the play progressed the writers seemed to have run out of ideas, rendering her superfluous at the end.

Another was the role of certain political personalities as they were very effectively exploited in the drama. A fair look-alike was managed by Michael Ignatius as Bharrat. The two most successful were take-off versions of Anil Nandlall and Irfaan Ali. In their fictitious roles, Nandlall became the fiery Tybalt with entertaining effect, while Ali was a version of the Count Paris, pre-selected by her parents as a husband for Juliet and a pretender to the national presidency. This character, quite precisely played by an un-named actor, was one of the main sources of delight for the audience.

But while those ideas worked and provided much fuel for comedy, the drama did not find equal counterparts in the other household. While the Bharrat household was fairly rich in characters worthy of parody, the Granger equivalent was fairly bereft of ideas beyond the amazing look-alike played by Mark Luke-Edwards, the character of First Lady Sandra, and Romeo himself. Guyana’s volatile racial divide was well represented in the plot, but, in fact, it was one-sided in a number of ways, including more emphasis on ridiculing the PPP/C than the APNU/AFC.

The play benefited, as well, from the character of the Nurse, whose representation was another of the good ideas. But overall, this success was mainly owed to what actress Clemencio Goddette made of it in her sterling performance. The plot weakened somewhat towards the end, and this happened partly around the role of the Nurse. As the plot thickened, she was obviously surreptitiously paid off by Ali to thwart the Juliet-Romeo affair and twist things so he could end up with his bride. But the Nurse was also involved in another plot concocted by the priest. None of these achieved any clarity and collapsed in confusion.

Some of the best moments in the play, however, came in the cynicism around which it ended. Both Romeo and Juliet cast off their cloaks of the ideal models of the romantic lovers in their hilarious and crude refusal to die for each other. In fact, both turned out to be shockingly fickle and by the end, were equally superficially engrossed in romances with other people.

It was good parody that Romeo moved fly-like from Rosalind to Juliet to Juliet’s cousin, while the virtuous Juliet herself was no different and a true parody of the famed and fabled, faithful maid.

The play commented cynically but realistically on the youth of contemporary society in as much as it did likewise on their elders in the fields of race and politics. There was no resolution. The play failed to make a really strong statement because of its very tame ending. But it surely allowed reflection on the ills of the body politic. The flawed politics of the times will echo in the drama in spite of itself.

Singh and Benschop’s parody allows reflection on local politics in the wider context, never mind it was pre-election. It therefore could not pinpoint the illegal vote count that now hovers like the sword of Damocles over Guyana as a nation and over the president’s chair if it is occupied by one who assumes it by an unlawful declaration. Beyond any sanctions it might suffer, the country that has now assumed great importance because of its new-found oil industry is doomed to be remembered as a place characterised by rigged elections.

As previously avow-ed, national literature started out its reflection of national politics in quite positive fashion. The poets of the 1940s moved from imitative verse, slowly transforming it into statements of patriotism leading to the strong nationalism that pervaded the literature for decades right through the 1970s. In the 1950s, Martin Carter was to lend profundity, complexity and sensitivity to the nation’s political poetry in a unique fashion created by his genius. Although limited and given the misnomer of “political poet”, he did focus on politics and protested the worst of it at three different times in history – the 1953 British invasion, the racial hostilities of 1962 -64, and the oppressive politics characterized by vote rigging in the 1970s and eighties.

It needed a bit more distance in time and space before many more Guyanese writers, some of them from overseas, began to write tragically and satirically of the political period of the 70s and 80s. Fred D’Aguiar, chose satire in 1987, as did Pauline Melville and others who followed in the 1990s like Nirmala Sewcharran. Others chose a tragic bitterness like Sasenarine Persaud, while dramatists like Harold Bascom managed stark documents of dramatic art.

That outpouring started in the 1990s when Guyanese literature multiplied in different directions among writers most of whom lived in North America or Europe. Time and distance might have helped to see the eventual emergence of this political literature that treated very serious work about the gloomiest of political states in Guyana. 2020 is immediate, and it is too early to see the developments in either politics or literature.