(Jamaica Gleaner) As the coronavirus pandemic spreads like a bush fire throughout the United States, several Jamaican healthcare professionals on the front line tell of a brutal grind of attrition that has seen COVID-19 infections creep towards the one-million mark and deaths topping 45,000.

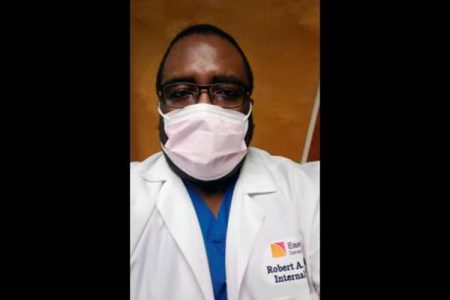

Dr Robert Clarke, who oversees a number of COVID-19 patients at East Orange General Hospital in New Jersey, recently saw one of his colleague doctors die from the virus. He was very blunt in his assessment of the situation confronting healthcare workers.

“This is a war, and we feel like we are being sent into battle with guns that have no bullets,” he said. In his estimation, they are not winning.

Clarke, who grew up in the gritty, crime-plagued south St Andrew community of Trench Town, said that he finds COVID-19 a more terrifying enemy than any gunman.

“It is emotionally and psychologically draining,” he told The Gleaner.

The physician, who also plans strategy at East Orange General, said that the crisis is spiralling out of control because of the shortage of protective gear.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency has exhausted its stockpile, delivering more than 11.6 million N95 masks, 5.2 million face shields, 22 million gloves, and 7,140 ventilators, The New York Times reported yesterday.

But the public-health system remains on the ropes, with US deaths nearing 4,800 and infections above 211,000.

Dr Trevor Dixon, who works at the Jacobi Hospital in the Bronx, said that medical professionals feel trapped in a real-life horror movie.

“It is scary, but we do our jobs because that is what we were trained to do. Besides, if the patients don’t have you, they don’t have anybody. They go through this all alone,” he said.

Dixon, who is an emergency-room physician, is concerned about the occupational hazard posed by asymptomatic patients – those who appear healthy with no apparent risk factors identifiable, only to die later.

“You, as a doctor, go through this every day, and you wonder if you are next,” he said.

It becomes harder, he said, as healthcare workers grapple with a dire shortage of personal protective equipment, such as N95 masks, increasing the risk of contagion from contact with infected patients.

But the risk is not only to the doctors and nurses, but also to their families.

“You go home, and on your way you tell your children to isolate themselves in their rooms before you enter that house,” Dixon told The Gleaner, adding that new house rules have had to be imposed, including no hugging.

The ER physician disclosed that he routinely disinfects his car, clothes, and everywhere he touches before entering the house.

“I have to strip down in the garage and take a shower before entering the house just so I don’t run the risk of infecting my family,” he said.

Dr Michael Morgan, who monitors 20 COVID -19 patients at Harlem Hospital, has similar stories to tell.

“It is hard to describe what we see happening with these patients, but you know that you are there to try and help them to recover,” he said.

Morgan, too, said that healthcare workers are under strain as hospitals buckle under the influx of patients.

“We go out there knowing that so many lives are depending on us, and we feel helpless because there is no cure that we are aware of,” he said.

Added to that stress is the danger that doctors face in being forced to recycle protective gear as hospitals scramble to source commodities that are in short supply.

“You find yourself wearing the same equipment for different patients. You have to carefully desanitise such equipment before seeing the patients not knowing if the virus will pass from patient to another or to yourself,” he said.

Morgan, too, said that he takes extreme precaution before interacting with his family.

One of the painful lessons is watching as colleagues on the front line become infected with the novel coronavirus.

“That really drives it home for many of us,” he told The Gleaner.

Claudette Powell, a Jamaican nurse who is part of the New York governor’s health team, has been on the sidelines watching the drama unfold. She was part of the team that went into the New Rochelle area when the virus emerged in that city.

Even though she is not directly interfacing with patients, Powell said that there is still high risk to herself and her family.

“They worry about me every time I leave for work, and I have to ensure that I take the necessary precautions to ensure that I do not put my family at risk,” she said.