This year’s celebration of Mashramani in Guyana was especially enhanced and accentuated because it was the Golden Jubilee of the nation as a republic. A special village was set up by the Department of Culture for a range of activities including stage performances, exhibitions of culinary arts, local films and literature.

This year’s celebration of Mashramani in Guyana was especially enhanced and accentuated because it was the Golden Jubilee of the nation as a republic. A special village was set up by the Department of Culture for a range of activities including stage performances, exhibitions of culinary arts, local films and literature.

The stage productions included sessions of storytelling and of folklore, including popular and supernatural folk characters and a variety concert labelled “Folk Night” with music, dance and dramatic pieces drawn from the folk traditions.

One segment of the presentations in the village that stood out was the staging of two plays, The Lottery by Sheron Cadogan-Taylor and The Slave and The Scroll by Francis Quamina Farrier. This was to be a minimised version of a drama festival for the Republic anniversary planned by the Department of Culture, but it was not realised.

The two plays that actually made it to the stage, however, had a worthy ring of significance about them since they bridged the gap of 50 years quite interestingly. One was from that period, more than 50 years ago, when the independent nation of Guyana was born and there was a strong spirit of nationalism and a sense of colonial history reflected in the drama. The second was a more popular type of play representing the contemporary stage in a society where laughter in performance befits the efforts through theatre to confront domestic discord and the struggle for a better life and prosperity.

The Slave and The Scroll was written in the 1960s when Farrier was growing up with local Guyanese theatre as a fairly new form despite adventures in drama developing since the 1930s. At that time the theatre was recovering from a colonial stage with a few local playwrights of note advancing including Frank Pilgrim, Sheik Sadeek, Slade Hopkinson, Bertram Charles and Farrier. This development overlapped with Guyana’s independence in 1966 going into republicanism in 1970. Although most of the plays of that era were not post-colonial in form, they largely reflected the enduring trend of nationalism in Guyanese literature that pervaded.

Cadogan-Taylor’s The Lottery was written in 2020 and falls among plays of social realism in modern Guyana that appeal to a popular audience and use comedy as a crowd puller and ticket seller.

Farrier showed what it was like in 1970 when the former British colony first became a republic, and Cadogan-Taylor took up the story 50 years later on a professional stage at a time of cultural change where the audience demand an entertaining reflection of their society, preferably in a manner that allows them to laugh at their folly and find temporary relief from the concurrent social and political stress.

The Lottery is set in the present Georgetown society riddled with domestic strife and domestic violence. At the same time there is the perennial dream of the working class, of the lower middle class, to get rich, to find the financial means to a more comfortable life. It presents a struggling couple – Sonia Yarde as the working wife, and Frederick Minty as her husband – in a delicately balanced situation where each contributes to the financial stability of the household, but the husband’s contributions seem, at least at the moment of the drama, a bit shaky and unreliable.

They both dream of one day winning millions in the lottery for which they each buy tickets regularly, but with little real expectation of winning. The relationship between husband and wife is warm and understanding, but is persistently on the edge, driven by mutual dissatisfaction with the economic well-being of the household and the questionable comfort of their home. This triggers off a fragility in their loving, caring attitude to each other which, driven by the material discontent, becomes brittle. Any little thing can send them cascading into violent quarrels, shouting matches and trading of insults. Though these never become physical and no blows are introduced, the vehemence of their words seem to threaten the worst.

Matters reach explosion point over the very dream of sudden riches starting off a series of ironies in the drama. The casus belli erupts over how they would share the millions when/if either of them wins the lottery – money that they do not even have (as yet). This exposes the ills lurking beneath the surface of the safety of their marriage, but rests on their inability to keep the peace and be nice to each other.

At this point the play became repetitive. While there was a lot of material for humour and audience entertainment, it took a while for the one-dimensioned plot to develop to a point where there could be any peripeteia. Yarde and Minty, both members of the National Drama Company (NDC), carried the drama very well throughout and helped the repetitious middle to benefit from lively acting in credible character playing and at a brisk pace.

The change in fortune comes with the entry of Paul Budnah, a police officer and very good friend of the couple. He struggles to separate the warring factions and get them to keep the peace but is very convincing in his performance while attempting it. The play ends in another major irony and a dramatic high point.

Cadogan-Taylor showed her high competence as one of the foremost directors on the Guyanese stage in the management of this play, assisted by the stage management of Budnah on a make-shift stage put together in a tent for the occasion. This kind of accommodation, however, is good for theatre and is actually the basis of a number of the super effective small theatre houses in Kingston, Jamaica.

Very interestingly, this play was invited to perform in Anguilla for that island’s drama festival, also in February. It played there along with a number of invited plays from other islands. The tiny island of Anguilla is building something, with the help of Guyanese talent, while Guyana seems bent on destroying and eliminating the thriving drama festival that it has (had).

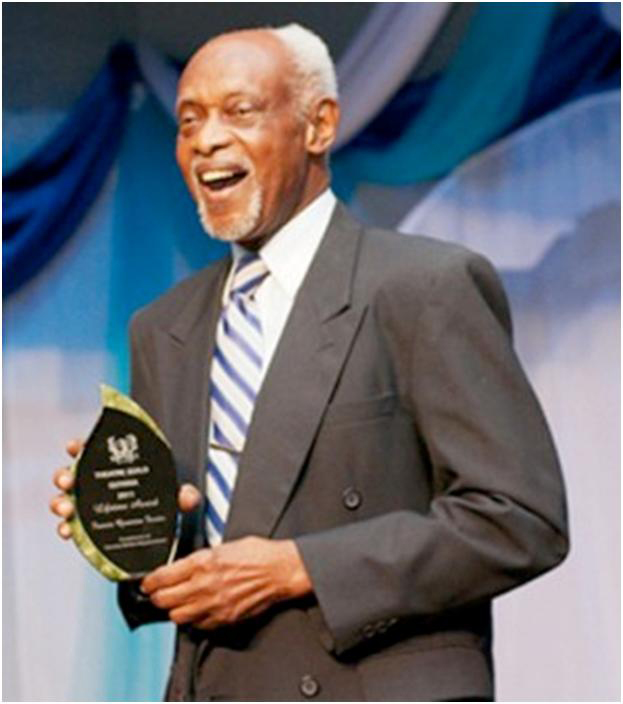

The Slave and The Scroll, directed by renowned dramatist Randolph Critchlow, took the audience back to quite another time and another type of drama. It was appropriate to the theme of republicanism because of the spirit of independence that most likely drove its author, Farrier, at that time when he was fairly prolific and turned out a number of one-act plays. This one recalls Mittelholzer’s My Bones and My Flute in the way spirits from the historical past challenge a group of people in the present to find their mortal remains and afford them a satisfactory final resting place. In Farrier’s play that resting place is a place in the history of Guyana.

The spirit of an enslaved African, played by Ron Bobb-Semple, draws persons from different places of existence and summons them for a rendezvous with him, and, indeed, with their own liberation. He gives them the task of finding the remains and an important scroll long lost in the dust of history and giving them a place of rest, permanence and meaning in the existence of the nation that the characters from the present inherit from the sacrifices of the enslaved Africans.

The setting is the ancient capital of New Amsterdam with its ring of antiquity and old memories, including the institution of Dutch and English slavery, and the revolutionary struggles of the enslaved against the system. This was also played on the make-shift stage, which Critchlow managed with sufficient effectiveness. It was straight realism without too many frills. It was meant to carry the feel of a different time, set as it is in an older version of the New Amsterdam known today.

The people gathered for the meeting with the former slave were played by Nirmala Narine (another NDC member), Radiante Frank, Nelan Benjamin, Colleen Humphrey and Sean Budnah.

Theirs was the task of making each character come alive, making something out of the fairly vague plot for the audience, and justifying their presence as individuals rather than as just one of a group. Accomplishing the tasks that they were set, however, depended on their ability to work together and set aside their differences. A message that rings true for an audience of contemporary Guyanese in a divided nation.

The vastly experienced Bobb-Semple, who came to the cast with a wealth of performance credits, was a bit of a disappointment. He had a commanding voice and some stage presence, but he did not make the character memorable, or his mission clear.

That programme of two plays will go down as a notable contribution to Mashramani and the celebration of Guyana as a republic. Each play spoke relevantly to its different time, the importance of those times to national social history, and the significance of the different types of drama to the periods separated by more than 50 years.