Eloise had followed close family members into teaching, going back at least two generations. She had hoped that the profession would remain in the family beyond her. She was open about the sense of achievement that she had felt for much of her life about her own mother rising through the ranks of the profession and eventually being appointed a Headmistress.

Teaching, Eloise was always proud to declare, had afforded her family the respect and the social recognition which she doubted could have been realised by any other means. It had not brought, though, the kind of material capital that you felt would leave you comfortable at the end of your exertions. Eloise, however, was too preoccupied with what she called “the other compensations” to worry about the downside.

As retirement beckoned, however, she remembered thinking all too often that the state pension which she had earned would not, even at the barest minimum of levels, sustain her, in what one would term a reasonably comfortable manner, right up to the end of her days.

In truth, however, her concern was not so much with the self-denial that she would have to endure in retirement but with the emotional ‘climb down’ that she was bound to have to endure if a point were reached where she had to look to someone else, even her two beloved sons, to keep her going.

Both Jason and Andrew had studiously resisted her deliberate and sustained attempts to steer them in the direction of teaching. Her world was not theirs. For her, appearances mattered. It meant everything to Eloise to be seen as Mrs Eloise Hercules, the widow of an upstanding, lower middle-class civil servant who had died leaving her with little else but respect, apart from the cottage in a lower middle class community on the outskirts of the capital.

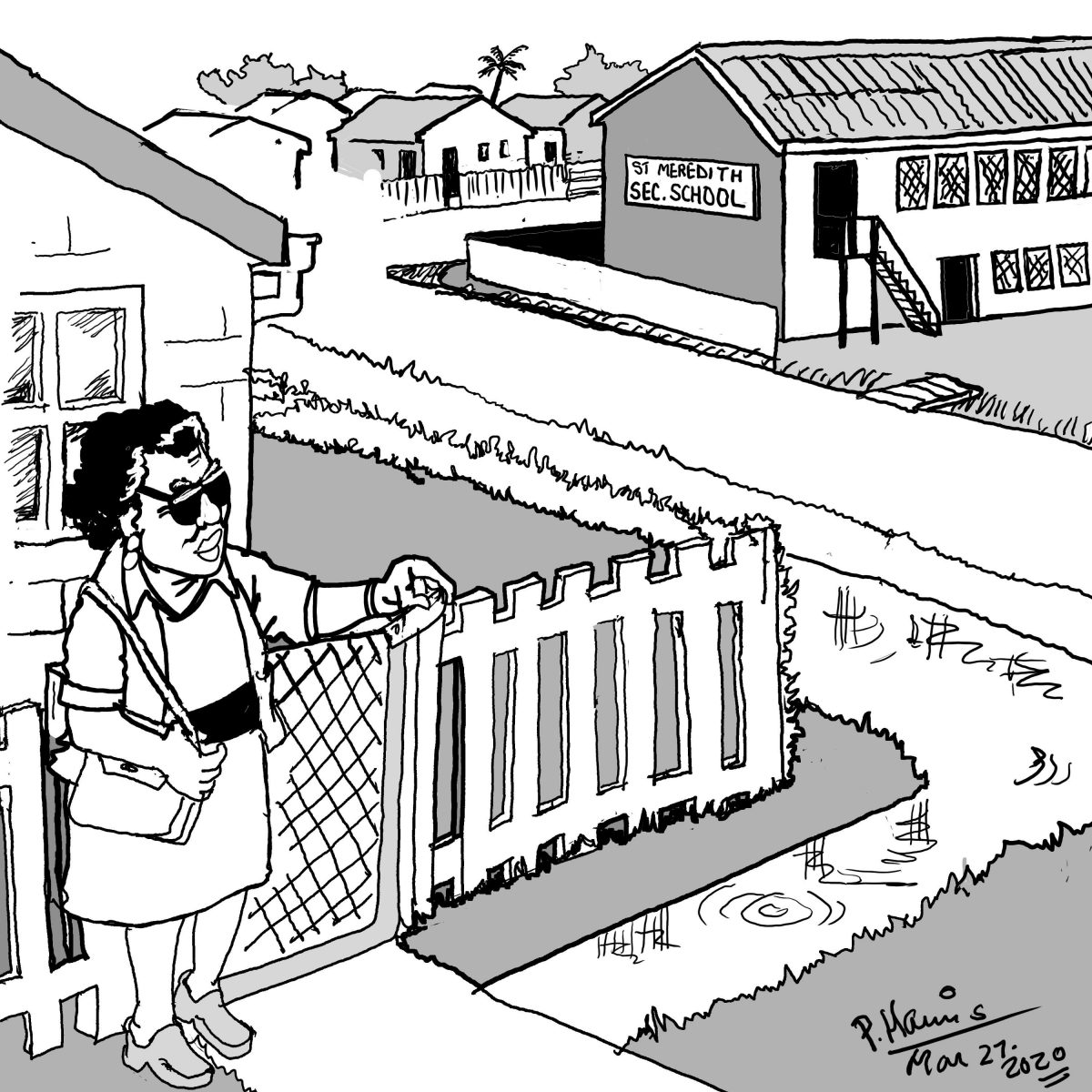

Her own professional pursuit had won her open respect in the community where she lived. It was, she had long surmised, by far the most important thing in her life, save and except her two boys. These days, the jaded cottage in which they lived was showing its age in a manner that the odd coat of paint and ‘patching up’ here and there, could not conceal. It was not that she was naïve enough to think that the exterior of the house had not been observed by her neighbors. She was, however, sufficiently confident that they respected her sufficiently to discreetly ignore the gradual decay.

After her husband had died her boys became her preoccupation. Providing them with what she had termed “a proper upbringing,” was, in her eyes, a matter of ensuring that they received a sound education. Nothing that she had done, however, would sway their minds in the direction of following her into teaching. It took a while for the boys’ mindset to get through to her. What their stubbornness eventually caused her to realise, however, was that much of her own life had become a clutter of delusions hinged on the fact that she had long embraced an altogether non-existent nexus between the societal recognition that teaching had earned her and the material means with which to live well.

She remembered that she had, over time, developed the sewing skills to conceal the darns and patches in the skirts that were more than a decade old but still served as part of her outfits with which to ‘turn out’ to school. Her dress was an exercise in public deception which she pulled off with all the grace and sophistication of a consummate expert.

But she could not fool everyone, not least her boys whose vantage point afforded them access to the ‘bottom line.’ They occupied ringside seats to the battle to make ends meet, whether that battle manifested itself in meals that were inadequate from the standpoints of both nutrition and ‘belly full,’ or from the need to wear items of clothing long after they ought to have been consigned to the garbage.

The boys hated the privation but they both loved and admired their mother. Even in their condition of being denied the things they craved, they felt that they owed her a debt of gratitude for the public respect that they had inherited on account of her own standing in the community.

Her last day as a teacher coincided with the end of a work week. The school held an elaborate ceremony to mark her retirement. She was showered with flowers and other gifts though, amidst the adulation that was being bestowed, she felt as though she had begun to embark on a journey that would end at a terminus of inevitable irrelevance. What worried her most was the fear that the end of her days as a teacher would, as well, strip her of the social standing and community respect that she had earned during those years when, every school day, she would step across the old wooden bridge that connected her cottage to the parapet and make her way to school.

Two altogether unexpected turns of events meant that the immediate aftermath of retirement did not quite go the way that Eloise had predicted. By now both of her boys had come to the end of their days at school and an uncle, a half-brother of her late husband, who had for years, run a reasonably successful printery in Georgetown, offered them both apprenticeships. The offer, not surprisingly, galvanised Eloise into one last- ditch effort to get the boys to apply for entry into the Teachers Training College. The effort, though, evaporated in an early Saturday morning discreet but tearful goodbye as the boys headed for the nearby bus stop to begin their own adult lives.

The second post-retirement development that impacted Eloise’s life was a visit she received, two days after seeing her boys off to join their uncle at his printery, from a group of neighbours – younger women with school-age children. They had come to ask whether, in her retirement, she was prepared to take on the job of a tutor to their children. The request had caught her cold. She had been, in the preceding days, trying to map out the rest of her existence but had come to no firm decisions as to the direction in which she would go. The proposal, Eloise surmised, could be a godsend. What she could earn from providing private tutoring for a few children would go some distance in subsidising her pension. Now on her own and with no additional mouths to feed she would be able to cope more adequately.

On the other hand, Eloise felt that there would be a downside to this new development. From her perspective of complete tunnel-vision, she perceived being employed to tutor her neighbours’ children privately as a huge climb down, an embarrassing concession that she had not, after all, and as might have been expected, retired into a condition of material comfort. The thought of it caused her to develop images of an eroded self-esteem arising out of now having to depend for the satisfaction of her needs on what she saw as a subsidy provided by the neighbours whose children she would have to tutor. And having thought about it, was forced to acknowledge that it gave her goose bumps. Moreover, she knew only too well that once she had to deal with the reality of the situation, the sense of reduced status which she was already feeling would grow worse.

Oddly enough, it was not as though Eloise Hercules had ever sought to create around her a sanctuary of grandiose elusions. Teaching and what it meant to the people in her community had imposed that ‘burden’ on her. Those were times when occupancy of certain positions came with a formidable host of expectations imposed by others. Respect came for Eloise but then, as well, came the burden of expectations. It had always been assumed by those around her that she knew better, that she had all the answers and that there were few problems that could possibly afflict the tightly-knit community in which she lived that could not be swept aside by her assertive and level-headed intervention.

After a few days she had worked out a strategy for addressing such unwholesome social perceptions as might derive from her decision to say “yes” to the job offer which the parents had pitched to her. She would gather them together and make a fairly long and passionate presentation about the importance of children receiving a sound education and how, reluctantly, she had decided to postpone her own retirement in order to help the children of the community be the best that they could be. She would, of course, be concealing the fact that the decision had been influenced considerably by ‘bread and butter’ considerations. Here, the ‘bottom line’ was that her pride and the public perception that obtained that she was doing the children of the community a service that derived from commitment rather than need on her part, was not a façade that could be tampered with.

There was a stunning sense of order to the tiny living room where she sat, relaxed, in a Berbice chair that was the better part of three decades old, waiting for the joiner to visit her. He was coming to discuss the erection of a shed beside her house where the classes would be held. She would raise with him as well the creation of some appropriate furnishings, desks, benches, a blackboard and a teacher’s table and chair. Ironically, his son would be part of the group to benefit from her private tuition. A knock on the door jolted her from her thoughts. She arose and headed in the direction of the ‘rap rap’ sound, the scent of the tobacco that the joiner was smoking assailing her nostrils even before she had opened the door.

It was at that moment that Eloise Hercules experienced a compelling feeling that she had entered a new, perhaps more liberated phase of her life. She felt as though, rather than having entered into a condition of retirement, she was only just starting out.