(Reuters) – Batting great Sachin Tendulkar famously said “if people throw stones at you, turn them into milestones” — a motto almost perfectly encapsulated by the cricket career of Sri Lankan spinner Muttiah Muralitharan.

Few modern-day athletes have endured more scrutiny than Muralitharan, whose bowling action was subjected to frequent and intrusive analysis, and even fewer emerged stronger from controversy.

The legality of the off-spinner’s bowling split opinion and as controversy raged, the International Cricket Council (ICC) conducted extensive tests.

The sight of a shirtless Muralitharan, sensors on his bare torso and a dozen cameras capturing his every move, bowling before biomechanical experts at the University of Western Australia, remains a powerful image of an athlete’s bid to salvage his reputation.

On another occasion, he bowled before TV cameras with his bowling arm in a steel brace to prove his bent arm was congenital and not conspiratorial.

That he still finished his career with 800 test wickets and 534 scalps in one-day internationals — benchmarks in both formats — proves his biggest asset was his iron will.

The test tally is the bowler’s equivalent of Don Bradman’s fabled average of 99.94 — a feat unlikely to be eclipsed.

As a bowler, the off-spinner from Kandy was a freak of nature.

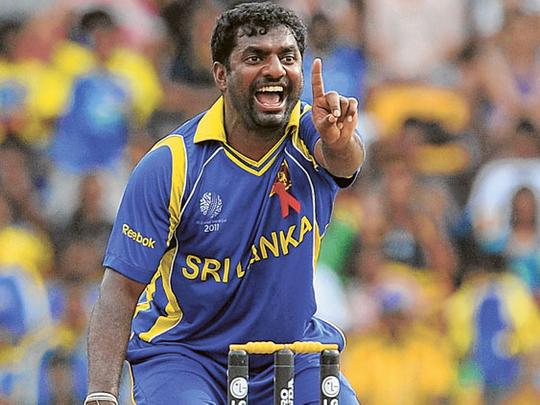

In cricket, it is usually the pace bowlers who strike fear into their opponents. Yet Muralitharan, with his bulging eyes, was a rare spinner who terrorised batsmen.

Former Sri Lanka captain Duleep Mendis once remarked that ‘Murali’ could turn the ball even on concrete and it was no exaggeration.

Blessed with a rubbery wrist and strong shoulders, Muralitharan simply took the surface out of the equation and was unrelenting and often unplayable.

Whispers, however, grew about his bowling action.

Australian umpire Darrell Hair no-balled him seven times in the 1995 Melbourne test. Ten days later Muralitharan was no-balled repeatedly by Ross Emerson in a one-dayer. In January, 1999, Emerson called him again in Adelaide.

Every time he readied for a fresh spell, the merciless Australian crowds shouted “no-ball”.

Yet those no-ball calls in 1995 perhaps proved a watershed moment in Sri Lankan cricket, as the team and Muralitharan went on to win the World Cup the following year.

“I think the no-balling of Murali was what drilled us together into a World Cup-winning unit…” team mate Kumar Sangakkara wrote in Wisden magazine.

“Buying into this Sri Lankan team as ‘our team’ and Murali as ‘our Murali’ gave us a goal…

“We know what can beat the elite, we just need to believe that. And Murali gave that belief.”

Extensive tests arranged by the governing ICC concluded that his action created an “optical illusion” and eventually a 15-degree flexion rule was agreed for bowlers.

The Wisden cricket almanac in 2002 ranked him as the leading bowler in history, ahead of Australian spin rival Shane Warne.

While he polarised opinion, the ever-smiling spinner, often the lone Tamil in the team, was a powerful symbol of unity in a strife-torn nation.