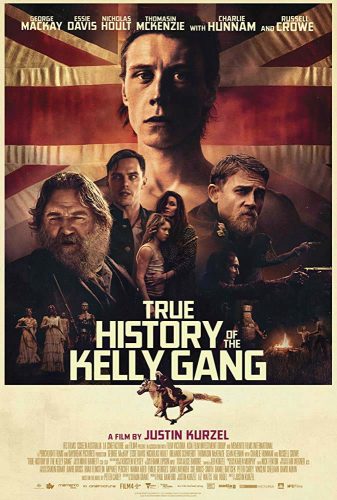

It makes sense that Australian director Justin Kurzel would get around to making a film about Ned Kelly, Australia’s most infamous outlaw. Kurzel has been preoccupied with violence for his entire career and the most thrilling moments of “True History of the Kelly Gang” are arguably the best work he’s done. The climax of the film is a dizzying shootout punctuated by a strobe-lighting effect and some thrilling sound design. It’s simultaneously thrilling and exhausting to watch, and comes after the film has worn you down with its rage. And it is rage that runs through the film, giving Kurzel’s inconsistent but exciting would-be epic a through-line that every aspect of the film clings to.

“True History of the Kelly Gang” is Kurzel’s first feature-length film set in Australia, since his debut “Snowtown” in 2011. And like with that film, it’s a fascination with the perverse that draws his attention. But not just the perverse. Screenwriter Shaun Grant adapts Peter Carey’s Booker Prize winning novel in unfussy fashion. There is little about the film that suggests any literary fidelity. Grant retains the novel’s quasi-epistolary conceit; the film becomes Kelly’s record of his life for his young daughter to read after his death. But the conceit is a mere peripheral frame here, whereas on the page it bled into language and form of the novel, and even into Carey’s resistance of elements of punctuation and grammar.

“True History of the Kelly Gang” is Kurzel’s first feature-length film set in Australia, since his debut “Snowtown” in 2011. And like with that film, it’s a fascination with the perverse that draws his attention. But not just the perverse. Screenwriter Shaun Grant adapts Peter Carey’s Booker Prize winning novel in unfussy fashion. There is little about the film that suggests any literary fidelity. Grant retains the novel’s quasi-epistolary conceit; the film becomes Kelly’s record of his life for his young daughter to read after his death. But the conceit is a mere peripheral frame here, whereas on the page it bled into language and form of the novel, and even into Carey’s resistance of elements of punctuation and grammar.

The result is that Kurzel’s film is less introspective than you would expect from one that flirts so much with being a character study. The idea of a “true” history suggests clarity, and yet motivations in the film are often opaque. We are quickly introduced to the tale of young Ned Kelly, who, despite no inherent motivations of his own, finds himself a pawn to the elements in the Colony of Victoria, Australia. He’s forced to take on the role of breadwinner when his mother’s resentment of his ineffectual father poisons him against the man, and so young Ned is fashioned in the image of notorious bushranger Harry Power – the beginning of Ned’s journey towards his own notoriety.

This “True History” seems to resist introspection at every turn. But it’s an opaqueness that creates intriguing complications, and one that seems to be by design rather than in error. Kelly’s own lack of awareness and foresight into his disastrous lifestyle becomes more complex by the film’s own disinclination to pathologise it. Instead, the film’s own engagement with violence feels like Kelly’s own self-reflexive use of violence as a spectacle. And, what a spectacle.

Cinematographer Ari Wegner relishes the opportunity to show off her skill with landscape here. There are familiar wide shots of open plains, and men riding on horses but they are no less good-looking because of this. The juxtaposition of nature as both beautiful and benign but remote and unforgiving runs throughout the film. Kurzel’s own sensibilities for the idea of the land as part of national identity add a subtle (perhaps, too subtle) layer of thematic resonance to the landscape here. Wegner is just as savvy with bodies as she is with landscape, and the introspection that the film elides is instead wrested from the way her camera confronts the faces and bodies of the actors. Bodies are framed in ways that always seem poised for something off-kilter. The most erotic scene, for example, is a stand-off between Kelly and a friend-turned adversary that establishes its carnality not from desire, but from the looming danger that bleeds throughout.

Even better than the presentation of bodies is the way that Wegner and Kurzel regard the faces that provide context within the film. Russell Crow’s grimace as Harry Power is a reliable early force. Meanwhile, Nicholas Hoult and Charlie Hunnam offer seductive takes on corrupt power, Essie Davis, as Kelly’s mercurial mother, is framed as though trapped by the camera throughout. Her performance is a necessary pillar for the film, even as her motivations are often unexplained it lends an air of reality to the film’s scope. It feels fitting, in a roundabout way, that these characters would be so resistant to understanding themselves. Instead, we are presented with tragedy without meaning.

And, it’s not to say that Kurzel and company do not recognise Kelly as a human. George MacKay, as Kelly, is working in a different register than his excellent work in “1917” but just as compelling. Here his furrowed brow is not a sign of obstinate focus but of trenchant ambivalence. Early moments of a young Kelly in a chaotic household do enough to set up our incredulity and sympathy, but the film rarely needles us for that sympathy as it goes on. We’re drawn to Kelly’s erraticism not because the film demands it of us, but because Kelly’s every glance feels layered with tenderness even at his most violence. It’s a striking dichotomy that complicates the film, especially as it hurtles to its close. It’s a kind of paradoxical casting that the film depends on – every surly glance from McKay screams angry young man, but every look from his baleful eyes seem to be full of despair.

By the middle of the film, the relentlessness of the chaotic violence and anger feels so fitting that the film’s own dependence on tropes that feel familiar makes sense. Kurzel’s occasionally superficial preoccupation with violence for its own sake makes more sense here than it did in his adaptation of “Macbeth”, for example, which seemed to bleed itself dry with its bloodiness. There is little subtext here, everything is all text – and writ large. “True History of the Kelly Gang” is not quite true or historical. It’s too averse to meditation for that. Instead, it’s a furious fever-dream of a man whose life is destined to be too short. If Ned Kelly’s life flashed before his eyes before he died, one would image that the flashes would be visceral and sensuous rather than thoughtful and contemplative. And, in that way, “True History of the Kelly Gang” feels apt.

True History of the Kelly Gang is available to stream or buy on Amazon, AppleTV and other steaming platforms.