(Reuters) – Charles ‘Sonny’ Liston has “1932-1970” and “A Man” inscribed on his gravestone, simple words for a boxing great whose complex life was shrouded in mystery despite being in the limelight.

With no birth certificate, census data suggests Liston was actually born in 1930 but he stuck by May 8, 1932, snarling at reporters who said otherwise and accusing them of calling his mother a liar.

Nobody knows the exact day he died either, with his wife Geraldine finding his dead body slumped against the foot of their bed on her return from a two-week trip in early January.

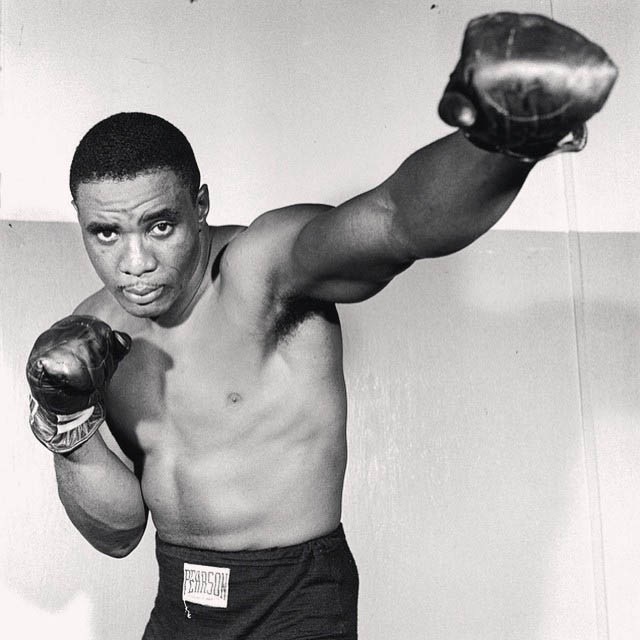

As for what kind of man he was, Liston was a phenomenon in the ring, leaving a pile of human rubble in his wake as he ascended the heavyweight ranks to become world champion.

But his links with the underworld persisted and, for much of his early career, the bouts he won kept pace with his arrests. Police in three different cities gave him a hard time.

Liston’s criminal record — he was found guilty of larceny and robbery as a teenager — did not help him but it was in prison that he honed his craft with the guidance of a priest who took him under his wing on seeing his imposing physique.

Liston’s trainer Johnny Taco called him a “killing machine” because he had the strength to knock opponents across the ring. His fists measured 14 inches, so huge they had trouble getting gloves on him after his hands were wrapped.

However, despite impressive victories, Liston was at first denied a heavyweight title shot by Floyd Patterson who refused to fight him on account of his links to organised crime.

When Patterson did put his title on the line in 1962, he was floored in the first round with a left hook for the third-fastest knockout in a world heavyweight title fight.

Liston thought he would be embraced by society — a villain-turned-hero who had put his past behind him — but he was wrong. America was in the midst of the civil rights movement and those fighting for equal rights shunned a black felon.

A Patterson rematch a year later lasted four seconds longer and ended with the same result but Liston was booed again.

“The public is not with me, I know it”, he told reporters, as quoted by biographer Nick Tosches. “But they’ll have to swing along until somebody comes to beat me.”

That somebody was at the fight — an undefeated youngster named Cassius Clay who would later call himself Muhammad Ali.

Clay needed just two fights to dismantle Liston’s legacy.

The champion had not trained well and a shoulder injury he carried into the bout prevented him answering the bell for the seventh round in an even contest, giving Ali the win.

Liston’s ego suffered a beating too after claims he could have carried on and the highly anticipated rematch a year later was far more controversial when he fell in the first round.

While fans were still getting to their seats, Liston was knocked out for the first time in his career by a glancing blow many did not see and came to be known as the ‘phantom punch’.

The photograph of Ali glowering over the sprawled Liston would become one of the sport’s most iconic photographs as he yelled, “Get up and fight, sucker!”

Liston got to his feet but he had been counted out by the timekeeper and the referee stopped the fight as fans booed the end to one of the shortest heavyweight title fights in history.

He could not shake off allegations he threw that fight and never had a title shot again.

“I think Sonny gave that second fight away,” his wife Geraldine told ESPN 35 years later, explaining how she had confronted him. “He said: ‘You win and you lose, you know?’.

“I said, ‘In the first round?'”