Nothing in the deliriously trippy “Ema” is accidental. Instead, Pablo Larraín’s nervy drama deepens in complexity when you try to dissect any individual moment. The first shot seems like an easy metaphor at first as we watch a traffic light ablaze on an evening street. It is as if Larraín is confirming that there are no rules about comings and goings here; all bets are off. Few symbols suggest wild abandon like fire. And, fire is central to “Ema”. We hear it crackling before we see the title and throughout its 102-minute running-time, the promise of fire is as much a metaphorical artistic motif as it is a literal manifestation of its characters’ transgressions. The opening flames are a promise and a threat. “Ema” intends to consume the audience, in the same way that its characters are consumed by their desires.

Nothing in the deliriously trippy “Ema” is accidental. Instead, Pablo Larraín’s nervy drama deepens in complexity when you try to dissect any individual moment. The first shot seems like an easy metaphor at first as we watch a traffic light ablaze on an evening street. It is as if Larraín is confirming that there are no rules about comings and goings here; all bets are off. Few symbols suggest wild abandon like fire. And, fire is central to “Ema”. We hear it crackling before we see the title and throughout its 102-minute running-time, the promise of fire is as much a metaphorical artistic motif as it is a literal manifestation of its characters’ transgressions. The opening flames are a promise and a threat. “Ema” intends to consume the audience, in the same way that its characters are consumed by their desires.

“Ema” takes a potentially straight-forward concept – a story of a dancer/choreographer recovering from tragedy – and delivers a film that resists definition and explanation at every turn. There are a number of discrete plotlines here: two couples coming apart, a reclamation of motherhood, and a tale of two dances. But “Ema” is as mercurial as its protagonist and from scene to scene it feels like it’s a film about something different each moment – a sexual thriller about perverse people, a dark love story, and a celebration of dance. “Ema” is all of these things and none of these things.

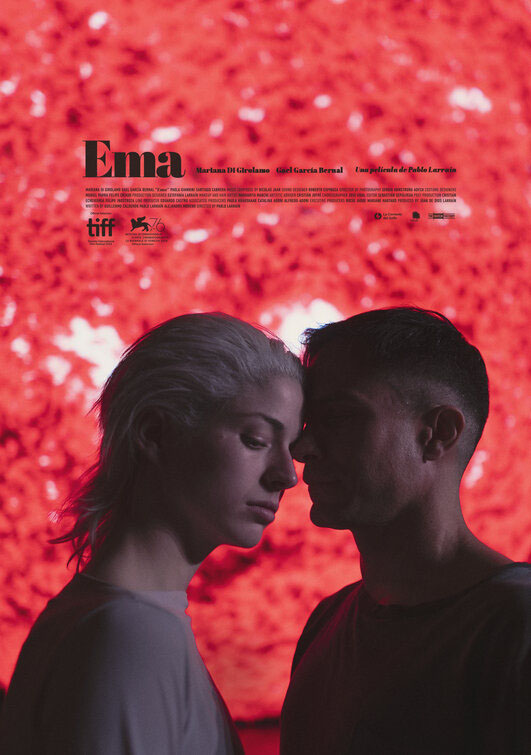

After Polo, an immigrant child that Ema and her husband Gastón adopt, burns down their house and injures his aunt, the two return him. It’s not clear whether it’s an act of contrition or guilt. The specifics of the incident are vaguely suggested in flashbacks, and in one of those flashbacks the couple is urged to regroup as if nothing has changed. “What do lizards do when their tail is cut?” a well-meaning family member asks. The answer she wants is that they simply grow a new appendage, but Gastón recognises that that simplicity is myth. “They get disoriented. They’re f**ked up,” he responds. Rebirth only comes after disorientation, and “Ema” is that disorientation in action. We are not truly privy to moments of great interiority from Ema, played with ferocious opaqueness by Mariana Di Girolamo, but “Ema” plays like a requiem of a former life. Or, a fiery exultation of grief. This is the disoriented space that Gastón suggests.

But “Ema” is neither sad nor tragic; it writhes with a heady and open sensuality that envelopes the audience. Long before we get to any certainty of what is happening, Sergio Armstrong’s camera keys us into the sensuality inherent to the tale. His camera moves achingly slow, teasing us with half-formed tableaus, caressing the bodies on screen and creating a hallucinatory melange of emotions punctuated by Nicolás Jaar’s excellent, ambient score. “Ema” wants to overwhelm us, and it does. We watch, complicit, as Ema plots a reclamation of her life with a coherence that feels dangerous.

By the end of the film, each preceding moment reveals itself as being incredibly worked out – symptomatic of a film that feels wondrously precise, even as it moves with a spontaneity that feels exciting. After its commercial release on MUBI at the beginning of May, Di Girolamo answered some questions about the film. She explained that she never saw a complete script for the film as they were shooting, and yet everything about the screenplay from Guillermo Calderón and Alejandro Moreno (two Chilean playwrights) feels incredibly worked out. The difficulty in establishing just what “Ema” is or is about is part of the film’s subversive dynamism. And within the perverse romance, and the story of mother and childhood, there’s a consistent awareness of social context that overwhelms the film.

That social context is there in the casual anger a social worker hurtles at the couple when she confronts them about the difficulty Colombian and Venezuelan children face at adoption. There’s a class tension in the relationship between Ema and Gastón that’s emphasised by the insults they throw at each other and the contempt they wield at each other and even their absent son. The couple seems simultaneously resentful of and desperate of the boy, reminding us that truth is elusive (and illusive) for these people.

The social context reaches to a climax in a moment that feels both allegorical and specific. “Ema” is not exactly about the schism between traditional dance and reggaeton and yet the invective Gastón delivers to Ema and her friends about the dangers of reggaeton feels pointed like the fulcrum of the story. After Ema abandons Gastón traditional dance company for a street-style reggaeton troupe, he admonishes her carelessness. Gael García Bernal’s anger as Gastón in that moment is alluring and dangerous. Reggaeton, unlike Gastón’s worked out routines, is spontaneous. And because nothing in “Ema” makes it easy for us, his thoughtful, if hypocritical, criticism is followed by a precise repudiation of his argument.

So, Gastón’s valiant argument against the “illusion of freedom” that reggaeton offers is followed by an extended musical sequence set to an original reggaeton song by E$tado Unido. For three minutes Larraín interrupts the narrative as the film becomes a music video where Ema and company dance through the streets of Santiago, putting the magnetism of the hot, crazy, sexy reggaeton beats to the test. Except, it’s not really an interruption of the narrative. The beat is hypnotic and the arrangement is pulsating, and as Stéphanie Janaina sings, ‘If my chest is real, my shadow is real. And if my hunger is real, my struggle is real’, the dance number begins to feel like a key to understanding “Ema” and Ema.

But it would be folly to extract that sequence, or any sequence, as the thesis of “Ema”. Just as the woman at its centre resists any attempts to figure her out, the film itself argues for the idea of a thing being more than its individual parts. “Ema” is a mood, a vibe, a feeling. Ambition does not mean value, and yet Larraín’s daring feels startling and powerful when measured against many of his contemporaries. Larraín refuses to give us peace, instead challenging us along the way so that by the end “Ema” feels like a deep dive into a disorienting world that is tough, and devious and elusive.

Hidden beneath the delicious contrivances and perversions, “Ema” is an invocation of the sensual over the cerebral. Larraín is forcing our hands, asking us to give ourselves over to the sensuality in a way that feels too dangerous to sustain. There’s a suggestion, at the film’s close, that there is something of a balance to be found – between Ema and trenchant reggaeton and Gastón’s histiographical folklore, or between flame thrower Ema and a firefighting romantic interest. Except, intellectualising “Ema” in some ways feels like missing the very essence of the film. So that to think of “Ema” we must return to those flames from the beginning. In some ways, it’s as if Larraín wants to engulf our idea of logic, of tradition, of norms. And so, pathologising “Ema” feels senseless. We can only see its thirst for flame as the beginning of a rebirth. What comes after that rebirth? It’s anyone’s guess, and we mull over the possibility on the brink of excitement met with trepidation. And “Ema” lives at that crossroad of the two emotions. It is that unholy mix of fear and anticipation made manifest. It is a singular piece of filmmaking.

Ema is available for streaming on MUBI.