At the end of the great novel Lord of the Flies (1954) by William Golding, the hero, Ralph, a 12-year-old schoolboy, cries. The narrative comments that he cries for the end of innocence and the darkness in man’s heart, which are weighty issues treated in the novel. Yet the plot of this tale takes the reader through a story about children left on their own and playing games, although of course, that is only the simplistic surface of it. It is a major work of irony.

At the end of the great novel Lord of the Flies (1954) by William Golding, the hero, Ralph, a 12-year-old schoolboy, cries. The narrative comments that he cries for the end of innocence and the darkness in man’s heart, which are weighty issues treated in the novel. Yet the plot of this tale takes the reader through a story about children left on their own and playing games, although of course, that is only the simplistic surface of it. It is a major work of irony.

Lord of the Flies is a novel about power. It is set in a time of war and deals with the primitive lust for power in the very depths of the mind of man; war and the consequences of war when the super-ego is stripped away and the unfettered id takes command in an uncontrolled environment. It is a story about children in a make-believe world who play out their fantasies. This is very much like the fairy tales, which can be frightening when seriously studied. And, like all those fables, speak to the real contemporary situation.

The applicability of the concerns of these great novels to universal principles and at the same time to familiar specific events is remarkable. In Guyana, there is a story about power. Here, is a reality, just like in the fairy tales, of the primitive lust for power seen in grotesque ogres, evil witches, and cruel stepmothers. “Mirror, Mirror on the wall, who is the fairest of them all?” asks the queen in her vanity. But she refuses to live with the truth as revealed by the mirror and must use all means and machinations to remain the fairest. Guyana’s story is about the end of innocence for a nation awakened to the reality of the depths to which man is prepared to sink for the possession of power. Those in power are willing to ignore the results of an election and suffer no discomfort from the fact that the whole world can see what they are doing.

The applicability of the concerns of these great novels to universal principles and at the same time to familiar specific events is remarkable. In Guyana, there is a story about power. Here, is a reality, just like in the fairy tales, of the primitive lust for power seen in grotesque ogres, evil witches, and cruel stepmothers. “Mirror, Mirror on the wall, who is the fairest of them all?” asks the queen in her vanity. But she refuses to live with the truth as revealed by the mirror and must use all means and machinations to remain the fairest. Guyana’s story is about the end of innocence for a nation awakened to the reality of the depths to which man is prepared to sink for the possession of power. Those in power are willing to ignore the results of an election and suffer no discomfort from the fact that the whole world can see what they are doing.

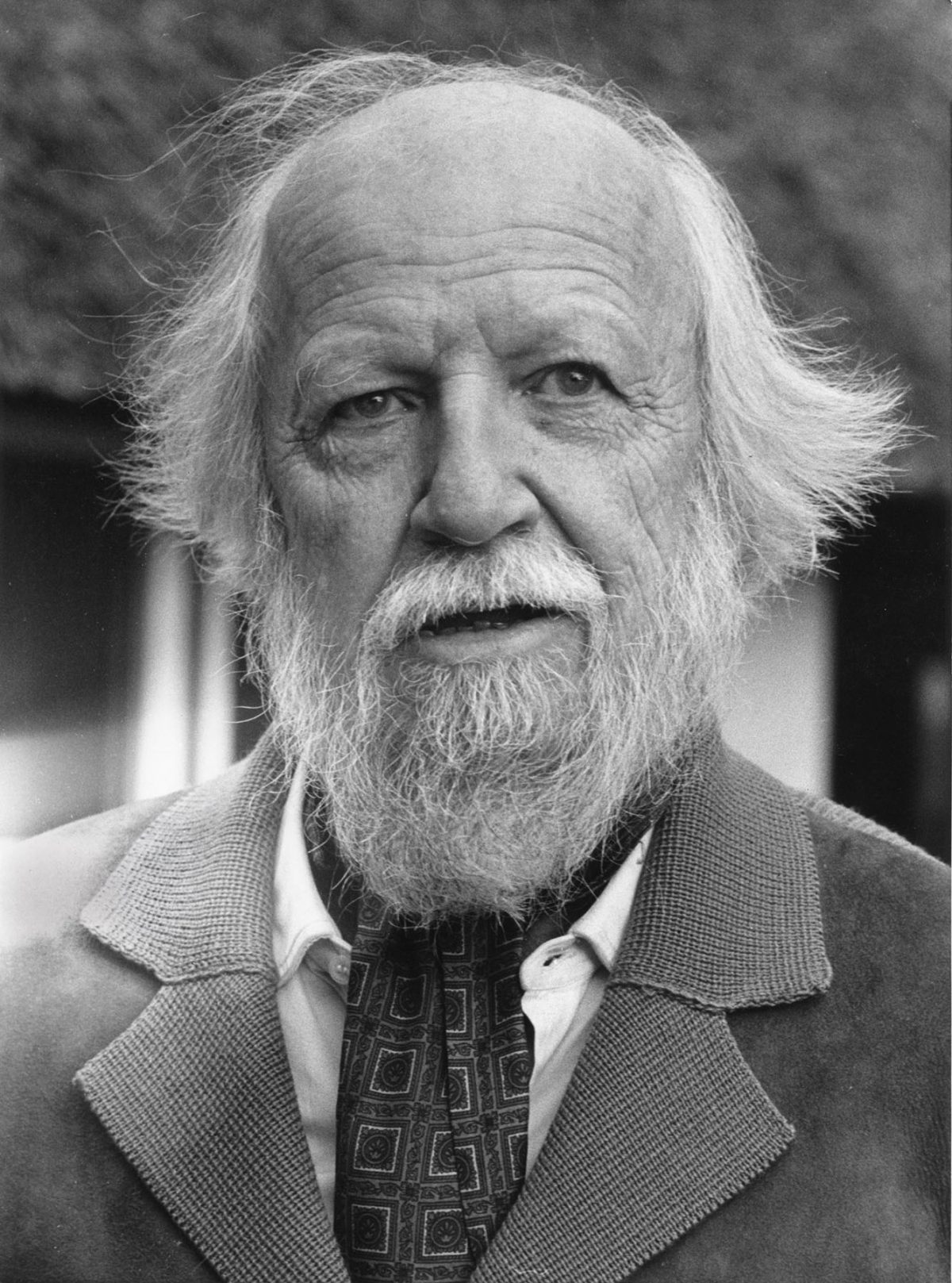

William Golding, like the long-living, all-seeing Tiresias, has “fore-suffered all”, has seen it already, and recorded it in his novels. He was among three of the best contemporary novelists shortlisted for “The Booker of Bookers”. This was a special award offered on the 25th Anniversary of the Booker Prize – renamed the Man Booker Prize, for the best novel out of all the Prize winners over the 25 years. Golding was shortlisted along with Salman Rushdie and V S Naipaul. Even outside of that honour, he has been widely acclaimed as one of the most distinguished fiction writers of the twentieth century.

Lord of the Flies is one of the universally acknowledged outstanding modern classics in which Golding unravels a plot about this maddening and dehumanising obsession with power and the evils of war. But very much like the fairy tales, he weaves the web of this plot deceptively among children. It recalls such other all-time greats as the allegorical Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) by Lewis Carroll, disguised in a fantasy dream world of magic and madness, among talking animals and characters and a queen whose favourite instruction to her court is “off with her head!”. The grotesque is mixed with the laughable and the fantastical, like the white rabbit, busy with important affairs of the court, who is desperately late, lamenting and inordinately glancing at his watch. This is another of the best-known allegories of the Victorian world, pretending to be a story for children. In this respect it follows the fairy tales, adopted as entertainment for children, but which are the horror-filled beliefs of a mediaeval adult world.

Another of the best-known novels of this ilk is George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945), fraught with all the tricks and treachery of modern politics and oppressive dictatorships. It was actually originally subtitled “a fairy story” with a child’s world dramatis personae of talking animals, but that subtitle was soon dropped, and it is qualified by Penguin Books as “a chilling fable”. It is clearly a political allegory with what some interpreted as a cynical reading of revolutions, but on closer reading is seen more accurately as a revelation of the betrayal of revolutions and of the working class.

Lord of the Flies is of that deceptive type and constructed on major ironies. It is wartime and a large group of British schoolboys are being evacuated, but in the process, their plane crashes and they end up marooned on an uninhabited island. Isolated, and with no adults present, the boys discover that they have to fend for themselves and survive. Their only contact with the adult world are the occasional signs that the war is in progress, and to make things worse, a passing ship fails to pick up their SOS signals and sails on.

Being educated, civilized English boys, they decide to organise themselves for better survival, and decide on roles of leadership, division of labour and rules by which all would be governed. Ralph emerges as the natural leader and is elected as such. Influenced by Piggy, the most intellectual among them, they establish quite a democracy, while their elders out in the wider world are fighting a war. But this peaceful democracy begins to fall apart when Jack starts to feel that he should be leader and leads a rebellion against Ralph. Additionally, the boys hunt wild pigs for food and develop a lust for blood as primitive hunters, and a lust for power led by Jack. War breaks out, Ralph is attacked and has to fight for his life against Jack’s savage band of killers. He, and indeed all the boys are rescued, when a large fire started by Jack to flush Ralph out of hiding, attracts the attention of a passing naval vessel and the commanding officer comes ashore.

A few things become important to the plot and its themes. The first is the attempt at civilized society. The second is the development of envy and rivalry, resulting in an open battle for power. Therefore, a power struggle develops. The third is a descent into savagery as the boys move from parliamentary civil organisation and become hunters – primary food gatherers seeking survival. There is also the absence of any message from the outside world controlled by adults. The only messages are reminders and remnants of the ongoing war. There are only two adults appearing in the novel – one is a fighter pilot who ejects from his plane but lands dead on a hill on the island, while the second is the naval officer whose battleship pulls up on the island to investigate the raging fire.

When the naval officer begins to interview the weeping Ralph, and then sees the band of “savages” who were chasing him, and who also once again become little boys and breakdown in tears, he expresses disappointment. He is disappointed at the pathetic state of the youths, who should be behaving like bright, noble British boys.

But the ironies begin to multiply. Here is a well-dressed, dignified, coherent British officer of war facing a savage band of half-naked boys “playing” at war and breaking down in tears. He is disappointed as he expects better of well educated, intelligent, civilized English youth. But really, they are not “playing” at war. This is the real thing. His arrival prevented Ralph from being killed. Other boys have been killed.

To make things worse, the fight to the death among the boys on the island is an accurate reflection of the savagery in the adult world led by the naval officer, who then turns around to chastise them. Ralph’s tears are for him and the kind of so-called, civilized, ordered world that he represents. Ralph’s tears are for the end of innocence – seeing behind the deceptive neatness of uniform and stoic consciousness of the commanding officer and his stately ship out in the sea. The savagery into which the boys descended is the very state of brutal, murderous enmity into which the adults and world leaders have already descended. Ralph cries out of disappointment in them.

The descent of the boys into primitive existence is an illustration of the natural state of humanity. Mankind, shredded of the sane, cultivated influence, will revert to savagery. It suggests a “darkness in man’s heart”, what is called the “heart of darkness” in other novels by other writers such as Graham Green and Joseph Conrad.

These “natural” instincts manifest themselves in such things as the lust for power harboured by Jack, who would go to any lengths, including the slaughter of Ralph, to get it. It is illustrated in the ease with which the cultured, well-taught boys rolled down a slippery slope into bestiality and inhumanity.

However, what needs to be noted is that everything that can be said about those boys on the island can be said about the adult leaders of the wider society. When Ralph cries, Golding is saying his tears are for humanity. He is also saying the boys are indeed well trained and good learners. They were only doing on the isolated island, what their elders were already doing in the wider society. Furthermore, it was the war that left them unsupervised on the island in the first place.

This obsession with power, and the readiness to gain it through whatever savage means, can be found in many societies. This deep and primitive “darkness in man’s heart” is universal and common among the species. Golding’s Lord of the Flies speaks eloquently to the society right here.