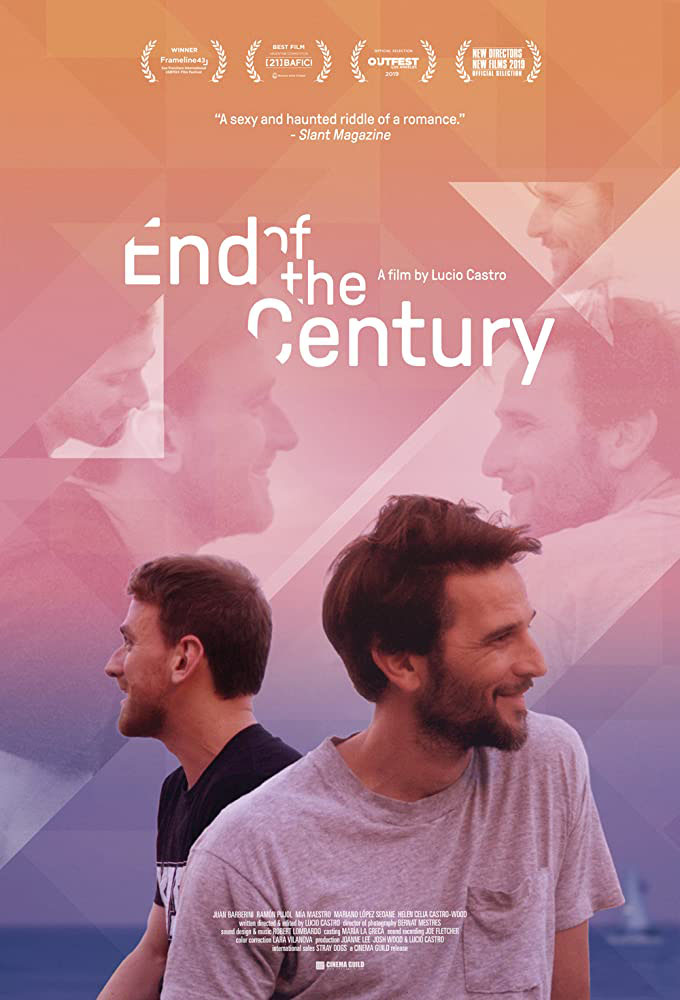

![]() There’s a tenderness to Lucio Castro’s debut film, “End of the Century,” that feels too fragile to be sustained. One imagines that a wrong touch could break it. The idea of a brief romance with life-altering consequences is central to the very best of cinema. And yet, even as cursory observations might project the shadow of a “Brief Encounter” or “Before Sunrise” on to Castro’s delicate romance, “End of the Century” is unabashedly its own thing – hazy and gentle, but still lacerating and ambiguous.

There’s a tenderness to Lucio Castro’s debut film, “End of the Century,” that feels too fragile to be sustained. One imagines that a wrong touch could break it. The idea of a brief romance with life-altering consequences is central to the very best of cinema. And yet, even as cursory observations might project the shadow of a “Brief Encounter” or “Before Sunrise” on to Castro’s delicate romance, “End of the Century” is unabashedly its own thing – hazy and gentle, but still lacerating and ambiguous.

The tentative what-if-romance is a mere 84 minutes and for the most of the first ten minutes, there’s no dialogue. Instead, we watch a restless dark-haired man strolling through the streets of Barcelona. This is Ocho. He checks into his Airbnb, sightsees, aimlessly trawls Grindr out of apparent boredom and observes the passing strangers from his balcony. One in particular, a blond in a KISS t-shirt, catches his attention and there’s a frisson of a spark between the two, even separated by an entire street. The two meet again later at a beach, but neither seems willing to pierce the tension that seems to loom over. It’s not until later that Ocho works up the courage to invite the stranger up from the street. So, the blond, Javi, enters the narrative.

Their casual sexual encounter borders on the amusingly banal (a mid-coitus condom-run is so very much of the current moment) and the awkwardness when they part seems curious for how charged it feels. Of course, they meet again – enjoying a European date of cheese and wine and as they have an energetic conversation that feels too precise for strangers “End of the Century” begins to mutate before our eyes. Because Javi and Ocho are, indeed, not strangers. And, thirty minutes into the film with a stroke of editing that displaces our idea of memory “End of the Century” hurtles back to 1999 as we watch the two men’s first encounter.

Beyond that, the plot seems antithetical to the languid mood that Castro is working to cultivate here. Just like in the present, in 1999 Barcelona meets Ocho aimlessly wandering through the streets, but this time carrying himself with a lot less surety than his 2019 self. But even as “End of the Century” is moving between timelines, Castro deliberately presents the past and the present as a singular atmosphere rather than one that is temporally distinct. Juan Barberini and Ramon Pujol play Ocho and Javi, respectively, in the past and present. Both actors, near forty, look younger than their ages but not quite young enough to play 20-year olds and yet there’s a willowy easiness to the way the film rejects any notion of trying to make them look like 20-year olds. Instead, it’s enough to watch the way they carry their bodies in the past to know that these are not the same worldly pair we meet in the film’s opening act but young men, still closeted, coming to terms with their sexuality.

But, each moment that “End of the Century” seems to flirt with a giant issue to hang its themes on, the film resists and deliberately evades anything too emphatic, opting instead for the congenial candour in something that feels too profound for fantasy but too casual for reality. Instead, “End of the Century” is a curious mix of both – a film that depends on multiple scenes of the two men walking and talking but makes use of framing and blocking in ways that feel immediately stirring. Castro has enough trust in his story and his craft (he also writes and edits the film) to evade emphasis, instead opting for a subtle fragility that is beguiling and frustrating.

Can someone you meet once really be the love of your life? And, are the what-ifs we create in our head actually wishes that we would want realised? The questions seem banal, but life is banal – which is what Castro deliciously leans into. The brief third act of the film puts these questions to test in a scene that feels too obvious to work but triumphs both because of Juan Barberini’s expressive face and excellent performance, and a series of precise cuts from Castro that feel like a punch to the gut when the film reveals its expected, but still affecting, conclusion.

In a way, this review feels preliminary. “End of the Century,” for all its willowy tenderness, feels too complex to be considered immediately. But the dull achy sadness that’s wrapped in ambivalence feels essential to the plaintiveness of the film’s ode (or is it a requiem?) to lost possibilities. Is it a love story? Or a story about Ocho’s own inability to resist his own isolation? There’s a scene early on where Ocho tries to explain his desire to be alone, even amidst his yearning for physical contact. It’s a familiar refrain, but no less effective because of that.

Castro’s inclinations are precise and indicate a filmmaker with a sharp sense of wonder in even the most mundane things. There are two scenes where Ocho interrupts a singing friend that feel foreboding and aching with its sadness. “End of the Century”, despite the largeness of is title resists any precious overtures at universality in a reach for a specificity that overwhelms. Ocho and Javi casually commiserate over their shared Argentinian heritage, foreigners abroad in Europe and the Casto maintains a casualness when speaking of countries that feels very contemporary. The film is never maudlin and yet when it expends its brief running time, it feels more moving than its initial casualness might suggest.

“End of the Century” is available for purchase on AmazonPrime Video an iTunes in Spanish with English subtitles.