It is not unusual on anniversaries to reflect on what is and what has gone before, and the independence commemoration is no different. There is much to mull over regarding what obtained pre-independence and post-independence, including evaluating development or lack thereof since the attainment of nationhood. However, actually doing it is not quite as easy if one is contemplating the arts. It is not so simple to draw a line and describe what happened before and after 1966. And this is the case when you want an analysis to achieve something less boring than common reflection.

It is not unusual on anniversaries to reflect on what is and what has gone before, and the independence commemoration is no different. There is much to mull over regarding what obtained pre-independence and post-independence, including evaluating development or lack thereof since the attainment of nationhood. However, actually doing it is not quite as easy if one is contemplating the arts. It is not so simple to draw a line and describe what happened before and after 1966. And this is the case when you want an analysis to achieve something less boring than common reflection.

There have, therefore, been more than one attempt to analyse pre-independence and post-independence Guyanese literature, without getting close to exhausting the subject. Literature does not work in that way. Nothing ceased on May 25 and was followed by something new on May 26, 1966. Colonial literature did not calmly step aside with grace at the lowering of the Union Jack at midnight to make way for the dawn of a new brand rising with the fluttering Golden Arrowhead. The colonial quality persisted in many ways for quite a few years, while nationalism and the dawn of a national identity were on the rise, surprisingly, some two decades earlier. Literature does not conveniently accommodate history by changing shape according to a dateline, or at the dictate of months, days, hours, which, according to John Donne, “are the rags of time”.

Neither do the arts in other disciplines. Artists who had been painting in a particular way for many years did not wake up on the morning of May 26 and decide that they would do so differently because they were no longer colonial and must now produce post-independence art. What is more likely is that historians will go back and study the art according to date and try to discern the trends that seemed to prevail in different periods. They might well find lines of development to which they can fix dates, but they will not find homogeneity of persuasion among artists in all the work up to a certain date, after which it all changes to something else. While it is true that events which took place on specific dates can have persuasive influence over art, there will always be overlaps. Old styles and subjects will carry over beyond any fixed date, while it might take a number of years before art begins to respond in shape, form or theme to the particular influence, impact, or effect of that specific event.

The attainment of independence is one of those specific dates and it is easy to divide pieces of work into those dated before and after May 26, 1966. But one will not find a clean, sharp difference between those before and those after. Surely, it was not “the rags of time” which caused artists to change, but more profound factors, most of which might not be time-bound.

Much of Guyanese art is post-colonial, but it depends on the preoccupations of particular artists long after independence, or on historical developments long before 1966. The development of the works of Philip Moore or Stanley Greaves are examples of the post-colonial predispositions of the individual artist, while the Working People’s Art Class is an excellent example of a movement that began to shape local Guyanese art long before independence.

Individual

But what is Guyanese art? What is pre-independence and what is post-independence? How do we distinguish these above looking at the date of production? Apart from the date, are there any distinguishing stylistic or thematic factors? Where these questions are concerned we have to divide them according to date of production, and having done so, examine the trends, and that is where we are going to find that many of these overlap. Some leading Guyanese artists are still asking if there is Guyanese art, what it is and what distinguishes it. Some are inclined to think that there is no type, form, or identifiable school of art that one can right away call Guyanese art because of its distinguishing, identifiable features. That there is no brand of art that has been created by Guyanese artists as a national collective.

That error is made because of an unscientific expectation that all artists need to be doing very much the same thing, and all Guyanese art must share some similar identifying mark or characteristic. But even national art is not going to be homogenous. In fact, there was a very interesting approach taken by Denis Williams, who founded the Burrowes School of Art in 1974. There was no library, and Williams brushed aside concerns expressed by saying, there was no problem; he preferred the art students to develop their own individuality, their own styles, and was not worried if they could not go to a library to study and run the risk of imitating other schools of artists.

In the five decades since independence, there have been strong trends, and important new developments, but all Guyanese artists have definitely not been doing the same things. Yet there is Guyanese art developed post-independence, and trends may be discerned that exhibit pre-independence Guyanese art.

What then, is Guyanese art? It is what Guyanese artists are doing and have been doing for some time. Yet, the most influential ones have not been doing the same thing. Before independence there were trends that involved large groups of artists, and were common among them, but there were also particular outstanding preoccupations pursued by individual artists that might have been unique but sufficiently significant to represent some notable aspect of Guyanese art.

One prominent type of Guyanese art is a whole corpus of landscape painting. This was the theme of an exhibition some years ago, the annual Independence Exhibition at Castellani House titled “Green Land of Guyana”, which was a take-off from a line in the national anthem. It echoed a nationalistic disposition in areas of Guyanese painting, a preoccupation found in some older work. It highlighted a period when landscape was a major focus in painting. So, one could say that was a factor in the national art, engaged in by a succession of several artists.

However, just as important was the landscape painting of Ron Savory, whose work stretched over a few generations, including a period pre-independence. But Savory’s landscapes add another dimension to the national landscape trend. This feature of the national art included a sense of patriotic pride, reflected in the theme of “Green Land of Guyana”. The natural beauty of the nation is flaunted in its many manifestations, and at the time when the type was popular among painters, there was growing nationalism in art, music, and literature. This started before independence and carried over with greater strength after 1966 and following Republican status in 1970.

Savory deepened these elements in the art with his innovations, including treatment of the Guyanese interior and the rainforests. While these are extensions of the general national pride, the Savory’s paintings studied the environment and its occupational predispositions, which became national statements in the art. A painting such as “Kamarang” focused on the seamy world of the pork-knockers with its dark areas and other companions to that work included the supernatural and the spiritual. Additionally, Savory innovated with style and technique, such as his hints of Impressionism and the use of the pallet knife. That, too, was Guyanese art. So is a particular series among the earlier paintings, depicting occupations around the countryside, including rice, cane-fields, and mining. Savory was a forerunner to others in the succeeding generation, some of whom also took up intertextual engagements with Guyanese literature as he did with Mittelholzer and Harris.

Extraordinary in the landscape treatment is the work of Bernadette Persaud who in the 1990s was interpreting Martin Carter as her new additions to the landscape treatment. She painted dystopia in a land invaded, echoing the ‘Poems of Resistance’ to British military occupation in 1953, but moving forward to the 1980s to interrogate the politics and the militarisation of the society as aids to oppression.

Like Savory, Persaud was launching off from the national preoccupation with landscape in realistic paintings, to greater symbolic studies. Soldiers with guns hidden in a corner of a green, beautiful setting in anti-pastoral representations. She deepened this in

yet another movement in the 21st century, further advancing significant Guyanese art.

‘Intuitive’

Worth noting, as well, is this movement away from realism. Realism predominated in pre-independence art, and definitely among the landscape works. In a number of scenic presentations, this escalated into excursions of ultra-realism. Many painters became preoccupied with it and the paintbrush imitated the camera in the capturing of fine, intricate, realistic detail.

Interestingly, at the same time when these were trends in the pre-independence art, there were other outstanding individuals creating unique work, significant Guyanese art. The Working People’s Art Class with Burrowes as one of its movers, inspired departures from the themes and styles of the 1950s. Some of the greatest contributions to Guyanese art was to begin to ascend with the sculpture of Moore, and the paintings of Greaves. Moore was a spiritualist, a visionary who accepted the carving tool as a gift from divine hands and used it to create some of the most outstanding suites of Guyanese sculpture.

His uniqueness is to be noted, yet there is the national label that his work assumed. There was, perhaps moving through the 1970s to 1990s, attempts at African sculpture in Guyana, which never caught on and was never elevated to the status of national art, being largely unremarkable and slightly imitative. But the work of Moore, who was an Africanist, made it to that stature. The difference was not only the distinctive quality, but the statement it made about art in Guyana. It often posed in the guise of intuitive art, especially his paintings, complex and minutely detailed on large canvases. While he remains inimitable, his influence is visible in 21st century painter Betsy Karim. But his extraordinary employment of symbolism opened an outstanding chapter in Guyanese art.

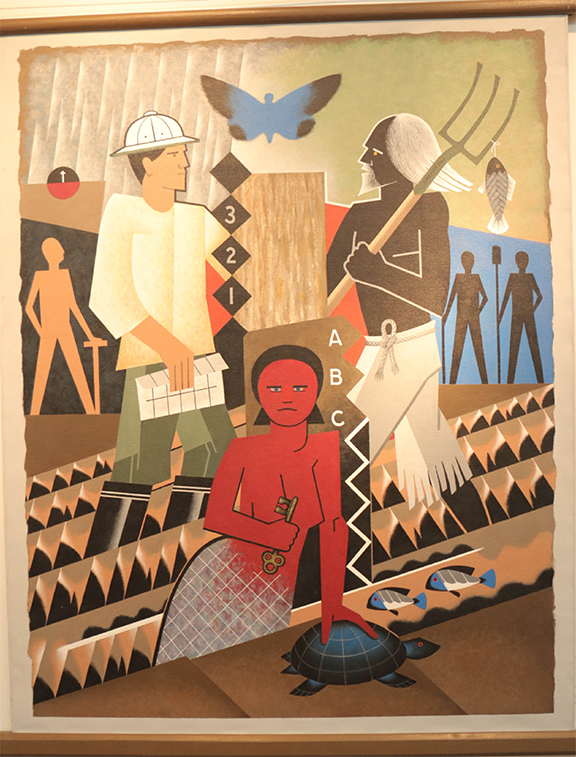

It is to be further noted that these individuals spanned generations and moved Guyanese art from colonial to post-independence, unbound within time periods. The exceptional work of Greaves attracted similar status from his early work before independence. Some of his small size paintings are “Wayside Preacher” and “String Band”. Like with Moore, characteristics of the intuitive, began to develop a unique signature known only to Greaves, but achieving such an impact to be recognised as representative of Guyanese art. To compound that, Greaves went on to complicate his canvases in the years covering the turn of the century and the first two decades of the 21st century. Two mighty exhibitions,

“The Elders” in London, jointly with Jamaican intuitive spiritualist Everard Brown, and the solo show “There Is A Meeting Here Tonight”, exhibited both the intuitive, the spiritualist, and the post-modernist in Guyanese art. They linked back to his “Wayside Preacher” painting.

It is, therefore, not unusual to have the work of individuals defining national art, in the remembrance that in national art all the artists do not necessarily do the same thing. Among the most recent to emerge of this ilk is the fast rising Elodie Cage Smith, originally of the French Caribbean, whose delving into history and slavery in a post-colonial and post-modern way is nationally significant.

National art is also a representation of the art of ethnic minorities, and art of the religions of the ethnic majority.

The latter is another reference to Persaud, while the former is to the extraordinarily striking rise of Lokono art led by George Simon and Oswald Hussein, and variations on that by Winslow Craig. Simon’s takeoff and ascent into the “Milky Way” and his “Shamanistic Journeys” also represent further modernistic representations, and these remind us of the infinite variety there is in what is defined as Guyanese art.