What does it mean for art to become political? The question occurred to me this past week watching the way protests against anti-blackness spilled out from the USA to the rest of the world after police killed yet another black life. As the outcry reached multiple continents, conversations about racism, anti-blackness, white supremacy and colonial precepts felt unavoidable. Even as America examines its own original sin and considers its specifically American problem of policemen as terrorists to black people, the questions of white supremacy that the incident spurred were a reminder that racism is not a foreign concept anywhere but, perilously, reaches everywhere. It is legion.

In the wake of the specificity of anti-black racism, which mutates in the way it affects different parts of the world, a full-throated reminder of the value of blackness in art felt essential. Even as the word ‘political’ is often avoided for what it implies, it seeps into every fabric of our lives. To be political is to be involved in issues of power that influence decisions that affect our society. Everything is political. Racism and anti-blackness are tied to power – who has it and who does not. And there is something essential in the power of the images we consume and what they tell us.

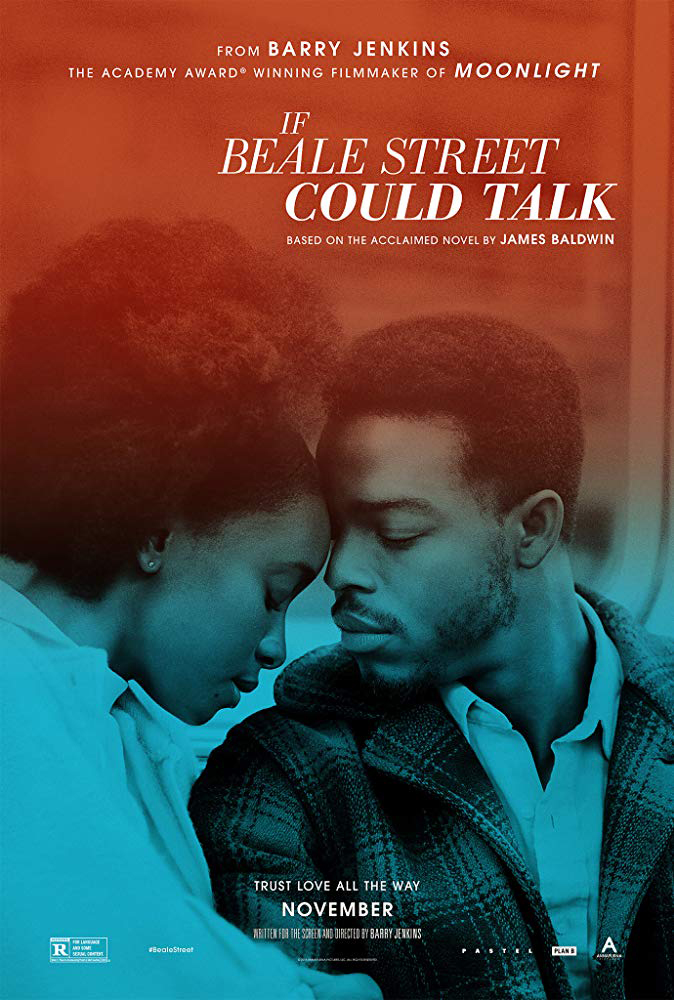

Film is a mirror of the best and worst of all, and that feeling was especially apt during this troubling week. On Thursday, police were beating unarmed protestors outside of Spike Lee’s New York office three decades after his “Do the Right Thing” felt too much of an essential cry to be ignored. The black women leading the multiple protests seemed like a manifestation of the value of black beauty, their images a representation of all the kinds of styles that black women used in Matthew A. Cherry’s Oscar winning short-film “Hair Love”. The need for visibility echoed the sentiments of seeing and not seeing that Ava DuVernay recent miniseries “When They See Us” argued for. There is a wealth of black art to consume, and I found myself turning to a recent favourite – one of the finest American films of the past decade and a film that feels even more politically proficient than in did two years ago, director Barry Jenkins’ tender and aching “If Beale Street Could Talk.”

There’s something beguiling about a movie that defies description, and part of the charm of “Beale Street” is that each summary of it seems inexact. Instead, Barry Jenkins spins the tale like gossamer – delicate and beautiful. The film is anchored by the burgeoning love story between Tish and Fonny (Kiki Layne and Stephan James in what should be star-making roles). The pair of childhood friends, turned lovers, have their relationship interrupted by a false arrest when Fonny is wrongfully accused of rape. The parents of the couple, primarily Tish’s, band together to weather the storm. The simplicity that defines the story is essential and, at first, deceptive. When James Baldwin wrote the original novel four decades ago, it was revolutionary for that very reason – the simple strength of a black love story.

On the page, and on the screen, “If Beale Street Could Talk” is a love story that represents a class of people too often forgotten. When Jenkins adapted the novel in 2018 (he wrote and directed it), the world had changed from the time of Baldwin, but what was even more troubling was the way the world had not changed. Jenkins’ “Beale Street” seems to be in conversation with Baldwin’s “Beale Street”, a discussion across eras as two black men perform a dialogue that resonates in both timelines.

Jenkins opens the film with a lengthy quote from Baldwin putting the original text, and the filmed adaptation, in context. Part of it reads, “Every black person born in America was born in Beale Street, born in the black neighbourhood of some American city, whether in Jackson, Mississippi, or in Harlem, New York. Beale Street is our legacy. This novel deals with the impossibility and the possibility, the absolute necessity, to give expression to this legacy.” Even as James Baldwin exists as one of the best American writers of the last century, his work has curiously not been fortunate enough to see big screen adaptations. So even if “Beale Street” were not as excellent, it still would be essential. The film is about a legacy of American blackness, but its potency is universal. But what Jenkins does is more than good, it is essential and exceptional.

On film, “Beale Street” becomes an expressionistic tale of benevolence that replaces word for images. The first time I saw “Beale Street”, at the 2018 Toronto International Film Festival the potency of its images seemed overwhelming. James Laxton’s cinematography is a gentle caress that acts out Jenkins’ central thesis – black bodies, black faces and black lives are valuable. And, those faces are everything in “Beale Street”. The film’s aesthetic reuses an element from Jenkins’ debut film “Moonlight” – the camera gets so close to the faces so when they look out at the camera it as if they are looking out at us. In a late scene, Regina King, in a miracle of a performance as Tish’s mother, Sharon, looks out mournfully at the camera after a moment of defeat. It feels as if she is looking at us, and seeing into us. Decades removed, the pain and resilience of the Black-American experience feels ever-present and it is not just mere representation but a challenge that Jenkins seems to be throwing out to us. Consider these lives and consider where we stand with them.

The exigencies of the plot are less significant than the film’s overwhelming atmosphere of blackness as a unit. The recurring themes that affect black lives in the seventies become evocative for the ways they persist into this century. In a single scene Bryan Tyree Henry speaks to the recurring hardship for black men in America as he confesses to an encounter with a policeman. “Beale Street” investigates the untimely incarceration of black men. It examines the ways that black women are forced to persevere with and sometimes for nothing. And, importantly, it offers an image of black family that is marked by solidarity and community. In the final scene of the film, a scene that is textually tragic, Jenkins manages to pull images of hope from a hopeless situation. It’s the metaphor of black existence spun into glorious colour, making something out of nothing.

There’s a moment early in the film where Tish confesses her pregnancy to her family – a black child born out of wedlock with the father in jail. It’s a story that seems too familiar in its sadness, except Jenkins recognises this isn’t sadness. As Tish hangs her head forlornly her sister (Teyonah Parris in a brief but searing turn) utters what feels like a vibrant theme for the film, “Unbow your head, sister!” And, that is what this film acts out. A glorious manifestation of blackness that is not unbowed.

A word like underrated is entirely too subjective a descriptor, and yet the world didn’t seem ready for “If Beale Street Could Talk”, even its minor awards run seemed more like the largesse from a “Moonlight” loving audience than a true recognition of what this film was, its own thing and not a pseudo afterglow of “Moonlight”. “If Beale Street Could Talk” feels like Jenkins’ masterpiece – a film, explicitly, its own thing but in some ways caged by the idea of what it was more than its existence.

In many ways, the superficial glance at “Beale Street” suggests little in the way of political earnestness. The film is a period piece set in the seventies – a love story of lives torn asunder by a wrongful accusation – and seems remote to the untrained eye. But “Beale Street” is not a perfunctory adaptation but a visceral account of blackness as resilient, tender and necessary.

The end of that quotation from James Baldwin which opens the film reads, “Beale Street is a loud street. It is left to the reader to discern a meaning in the beating of the drums.” I’ve been thinking a lot about what that means this past week. The way that anti-black racism manifests in the USA is not the same way it manifests in Guyana or in Trinidad or the UK. The black experience is not a monolith. And, yet, there’s a sameness to the anti-blackness that defines so much of the contemporary media. American’s race issues may not be global but American media defines so much of our culture around the world, and their media becomes a tool – whether deliberately or accidentally – of upholding the tenuous hold that white supremacy has on our psyche.

“If Beale Street Could Talk” interrogates, repudiates and subverts that. It presents blackness in glorious colour – both angry and tender, both mournful and hopeful, fragile in the way it aches but powerful like an echo resounding through the years. Right now, it feels essential and propulsive. Every frame of it announces that ‘Black Lives Matter’. And each frame, just by that fact, is political. Do we dare to follow Baldwin’s directive? Are we willing to discern the meanings it offers to us?

If Beale Street Could Talk is available for streaming and purchase on Hulu, AmazonPrime Video, iTunes, Vudu and other streaming services.