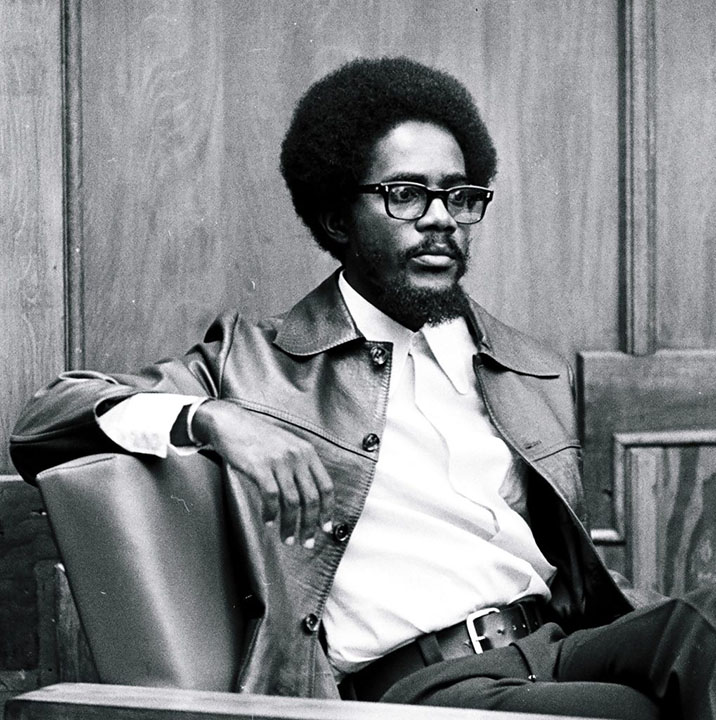

There is an important monument at the University of Guyana (UG) that was established years ago to honour historian Walter Rodney, who was assassinated on Friday, June 13, 1980 by a planted bomb in Georgetown. The Professorial Chair in the Department of History was founded by collaboration between the Cheddi Jagan government and the university as a symbol of his presence and to continue the academic and intellectual work in the fields to which he made contributions during his career. It was symbolic because he would have personally occupied such a chair if the Forbes Burnham government had not wielded its influence to block his appointment at the level of the University Council in the 1970s.

There is an important monument at the University of Guyana (UG) that was established years ago to honour historian Walter Rodney, who was assassinated on Friday, June 13, 1980 by a planted bomb in Georgetown. The Professorial Chair in the Department of History was founded by collaboration between the Cheddi Jagan government and the university as a symbol of his presence and to continue the academic and intellectual work in the fields to which he made contributions during his career. It was symbolic because he would have personally occupied such a chair if the Forbes Burnham government had not wielded its influence to block his appointment at the level of the University Council in the 1970s.

That Chair is now dormant and unoccupied 40 years and 2 days since the assassination, although it is the intention of the faculty to resurrect it. The Chair had been occupied sporadically with brilliant sparks of life. Its most telling impact was experienced during the incumbency of Professor Winston McGowan, during whose service, the various spheres of research, publication and public education in which Rodney worked were most effectively illustrated.

Outside of the Walter Rodney Chair, there were other activities at UG to keep these works alive, even when it was vacant. In 2005, UG got together with the University of the West Indies (UWI) St Augustine Campus and hosted an international conference as a 25th anniversary event. The idea that this was to be followed by another such at St Augustine did not fructify, although, quite independently of that initiative, there was a Rodney Conference at UWI, Mona several years later. Scholarly papers were read at UG in 2005 focused on the different areas in which Rodney worked, made contributions, or influenced.

These are the very areas that will be ignited by the refueling of the Chair. They are African History, West Indian and Guyanese History, Historiography, Post-colonialism, Globalisation, Economic History, Marxism, African and Indian Indentureship. These were themes of the 2005 conference. Missing from that list, however, is the field of culture.

Even in the Chair’s years of silence and dormancy, the Faculty of Education and Humanities kept his name alive in the area of culture with the Walter Rodney Prize for Creative Writing. Literature Lecturer Mark Tumbridge was the caretaker on behalf of the prize donors. An award was offered, alternatingly, for the best entries in Fiction and in Poetry by students at the university. The impact of this may be seen in at least two students who went on to achieve some national prominence after graduation. Subraj Singh, who was a winner in Fiction, progressed to win the Guyana Prize for Literature, represented Guyana at Carifesta and is now the most promising young writer in the country. Gabrielle Mohamed, featured in poetry, also represented the country at Carifesta and is among the rising contemporary young writers.

The Rodney name is thus associated with culture, the arts, literature. The prize is another way in which the university recognises his celebrated work and spheres of influence. It is also developmental in that it is an impetus and incentive for the growth of young creative writers.

But how did the celebration of the Rodney name in cultural affairs come about? He was a historian, a political leader, an activist and a revolutionary of Marxist-Leninist persuasion in scientific socialism. To paraphrase Shakespeare, ‘what’s literature to him or he to literature?’ The answer is, quite a lot. There were very close connections between Walter Rodney and the field of culture.

To begin with, he wrote creative non-fiction in two accounts of East Indian and African immigration – Lakshmi Out of India and Kofi Baadu Out of Africa – to deconstruct history for a youthful audience. Poet Edward Baugh, in satirical fashion, created the partly humorous ‘tradition’ of the “Rodney Poem”; and indeed, several leading West Indian poets took up Baugh’s tongue-in-cheek cast web and very seriously wrote celebrated poems as tribute to Rodney. These included Mervyn Morris and Martin Carter in an impressive corpus of Rodney Poems.

“The Walter Rodney Factor in West Indian Literature” is among various publications on Rodney’s legacy. Adding to the relationship between Rodney and Caribbean culture is one of his earliest publications, The Groundings With My Brothers, written during his time in at UWI in Jamaica in the 1960s. This is an account of his proletarian connections, virtually his fieldwork, among the working-class communities in Kingston.

As a Marxist, this was important political activism for him, and incidentally, work that got him in trouble with the Jamaica Labour Party government at the time. The authorities grew increasingly afraid of university men who left the safe confines of that ivory tower to ‘corrupt’ the innocent minds of the folk in depressed communities. They seized the opportunity when Rodney travelled to a conference in Canada to deny him re-entry and expel him from Jamaica on October 16, 1968.

But The Groundings With My Brothers became an influential cultural icon and manifesto among intellectuals, radicals and in popular culture. There is cultural and linguistic depth in the word “groundings” which referred to community, socialisation, dialogue and reasoning with the proletariat. Someone who was described as “grounds” in popular Jamaican language was deemed culturally and politically conscious, with a proletarian class position. The culture of “groundings” was to take off much more rapidly because of Rodney’s influence, the publication of the monograph, and his high-profile, explosive deportation from the country.

This culture began to take root in a society previously neo-colonial, under bourgeois influence, still fairly Eurocentric, and suspicious of anything black or African or working class. Such attitudes were led and represented by the government of the day, and their fear of Rodney was consistent with their ideology. At the same time, this slowly rising culture was beginning to attack them, and such a rising was escalated by the events that followed October 16, 1968. There was a growing alliance between radical politics and culture, the arts, music, theatre, and literature.

On the same morning of Rodney’s deportation, students rose up on the university campus. A large contingent led by the student Guild of Undergraduates marched from Mona to Gordon House (Jamaica’s House of Representatives) in protest. Incidentally, the Guild President and one of the student leaders was Ralph Gonsalves, who is now Prime Minister of St Vincent. The students battled police who hurled tear gas, but they made it to Central Kingston where they ended the torturous march. They returned to the campus and shut it down for two weeks.

However, the students’ activities on the streets triggered sporadic riots and violence among the townspeople long after they had returned to Mona. The physical violence downtown was matched by cultural upheavals uptown. Middle-class society began to open up to a number of influences previously excluded from the mainstream and regarded with suspicion. These included black and African consciousness, the acceptance of African culture, and the embrace of Rastafari. Black Power that had been making noises in North America found its way to the Caribbean and began to make an impact.

At the time, the Mona Campus was still highly multinational, and the foreign studentship came under heavy attack from the government which cried foreign interference. Both students and staff retaliated, defending and justifying themselves and their activities. All this was fertile ground for the cultural expressions with growing radicalism and antiestablishmentism. These infiltrated the wider society across the Caribbean. It was a definite gain for Rastafarianism which advanced along with cultural performance in music, including African drumming and the developing reggae music. The explosion in reggae was resounding between 1968 and 1970 when there was a concentrated succession of protest music.

One of the spinoffs was the famous occupation of the Creative Arts Centre (CAC) on the Mona Campus. The CAC was fairly new and was one of the real powerful advancements in the arts, not only at UWI, but in Jamaica itself, and in the wider Caribbean. This particular rising flared up in the wake of the long succession of post-Rodney repercussions and cultural activism that developed without a cessation in and after 1969, spreading to the St Augustine Campus in Trinidad, and out into the wider Trinidadian society. Several other things were happening, including the definite popularity of Black Power, but the rising was instigated by a student protest over an event they had planned being shut out of the CAC. This was a black cultural event, which was forced to give way to another event regarded as foreign and Eurocentric which was given preference for the use of the space. This escalated into a full-scale occupation and shut down of the CAC by students. Similar unrest was sparked off in Trinidad.

Among the best things that emerged out of these was a reorganisation of UWI Campus governance. The CAC was re-structured to include students’ involvement in its management. There was also a larger move towards co-management in the university with students’ representatives being included on a wider range of university boards and within faculties. The CAC advanced to be a major cultural influence nationally and regionally.

Several protests were accompanied by performances. These took the form of a major merging of middle-class, intellectual, academics and student artists with Rastafari, working-class and new, unestablished performers. Most of these took place in non-traditional venues and gave rise to Yard Theatre. The term “yard” is itself of linguistic significance, signifying as it does the yard – a proletarian and folk environment – as well as a space of communal involvement and progressive social identity. It was the “groundings” of those from the ivory tower with the people of the society.

There was much more that emerged and evolved from Rodney’s groundings and the cultural shock waves following his expulsion from Kingston, including important movements in literature and theatre.

Ironically in Guyana, the Working People’s Alliance (WPA), founded and led by Rodney, now finds itself in a pitiable position and state. It is now an ally, accomplice, and defender of the same political party against whom Rodney fought heroically to his assassination. He was resisting such ills as election rigging in 1980. The WPA is a part of a coalition that now strives to impose everything that Rodney resisted right up to June 13, 1980. The cultural waves that advanced from his activism and intellectual leadership continue today in his honour and to the dishonour of his political party.