Introduction

In today’s column I continue this extended appraisal of the likely future impacts of the 2020 global general crisis (as I have described this term in previous columns) on Guyana’s infant oil and gas sector. I have chosen the metaphor “a baptism of fire and brimstone” in order to dramatise the severe challenges that the 2020 general crisis pose for the country’s oil and gas sector within a matter of weeks, after the commencement of commercial production on December 20, 2019.

To recap briefly, the essential thread of this presentation is to frame my evaluation under the rubric of two time-frames; namely: 1) the short (near-term) to medium-term, and 2) the medium-term to the long-term (secular), respectively. Thus far, I have completed the first of the two tasks, except for the fact that I shall revisit the “near-term” in my summing-up of the evaluation. The reasoning behind this is that the approach allows more time to elapse, thereby aiding me in getting a better handle on emerging trends this year.

As indicated, the second time-frame is being evaluated from two strategic standpoints. The first is the long-term trend in global energy use, particularly because liquid petroleum and natural gas will come under growing threats in the future from clean energy sources. As revealed in last week’s column, the global transition in primary energy use from liquid petroleum to renewables is projected to occur before 2050, by the United States Energy Information Agency (EIA). The second strategic consideration is to establish the potential size of Guyana’s recoverable oil and gas reserves. I focus on this topic for the remainder of today’s contribution.

Guyana: Current Petroleum Resource Estimates

Because of the fundamental role the country’s resource potential plays in my evaluation, I’ll start consideration of this topic with a summary of Guyana’s petroleum resource prospects as publicly reported by the lead petroleum exploration, development and producing operators in the country. As readers are aware, the only crude oil commercial producer to date is ExxonMobil and its partners. Two other joint venture groups (JVs) have announced discoveries, but these have not been declared as commercially viable to date.

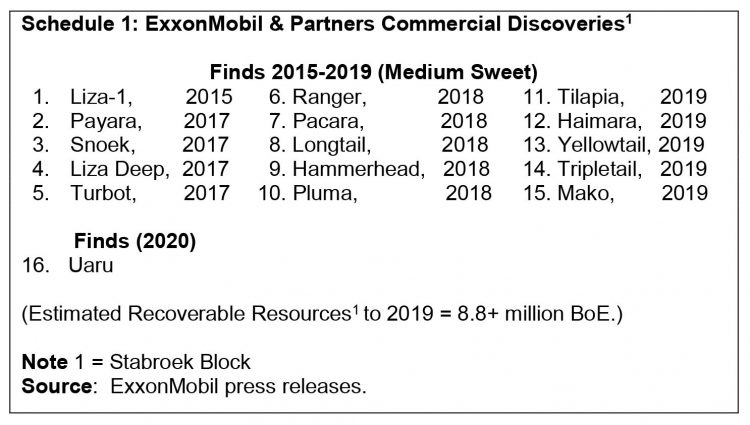

ExxonMobil and its partners announced their first offshore petroleum discovery in Guyana, in May 2015. Since then sixteen (16) discoveries have been made. Subsequent to the first discovery in 2015, four have been made in 2017 and five each in 2018 and 2019. For 2020 there has been one discovery. As I have repeatedly observed, this is a phenomenal rate of discovery worldwide, when substantial quantities of oil resources have been found. Guyana’s “creaming curve” (described below) is historically unprecedented. To date, all 16 discoveries have been made on the Stabroek block.

The estimated recoverable resource announced by ExxonMobil and Partners total 8.8+ billion barrels of oil equivalent (BoE). This total is for the 15 discoveries made to end 2019, as the 16th discovered resource potential has not yet been ascertained. These data are reproduced for readers’ convenience in Schedule 1 below.

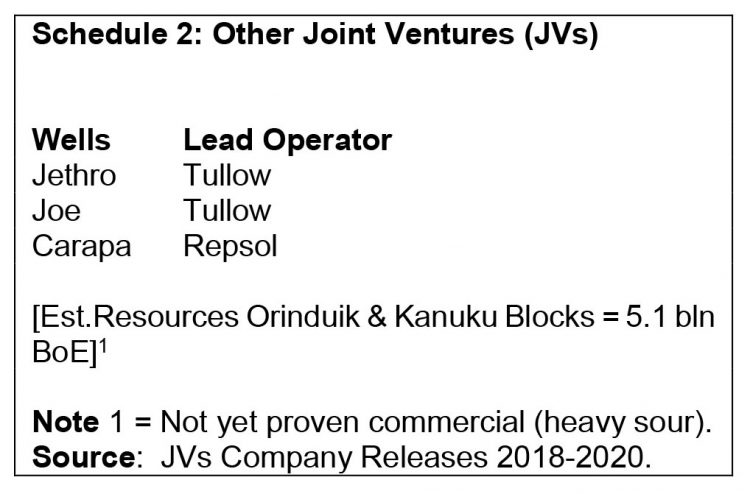

Two other joint venture groupings (JVs) have announced three finds based on Prospective Resource estimates totaling 5.14 billion BoE. These finds are Jethro 1, Joe 1, and Carapa wells. These estimates are obtained from an updated commissioned study: Competent Persons Report on Resource Prospectivity in their holdings, which was conducted by Gustavason Associates. These data are reproduced in Schedule 2 below. Note, all finds are located outside the Stabroek Block, in the Orinduik and Kanuku blocks.

Technics

I take the opportunity here to inform readers that S&P Global Platts has published the specifications for Guyana’s Liza oil in its Periodic Table for Oil. This interactive Table classifies Guyana oil as medium sweet. Its American Petroleum Index, API is 32.10 and its sulfur content is 0.51

Further, the creaming curve referenced above, depicts the relationship between cumulative aggregated volumes of oil reserves (on the linear Y axis) and on the number of wells dug over time (on the linear X axis). The steeper the curve the more rapid is the revealed rate of discovery, and vice versa.

Massive potential

I have been arguing since 2016 that, Guyana possesses “world class” resource potential of crude oil and natural gas (this will be re-visited next week). My estimate of 13 to 15 billion BoE was first offered at a time when, as we can see from the data on actual finds, there was only the 2015 confirmed estimation of 600 million BoE in Liza 1. I was widely denounced in the print and social media by the “noise and nonsense” hucksters as overly optimistic. As the saying goes, however, facts will win in the end. I am pleased for Guyana that my projection wasn’t widely optimistic. Indeed, several analysts and specialists, as well as energy-intelligence firms are today expressing views that are deeply skeptical of the conservative estimates of ExxonMobil and Partners, that remain on record.

Thus recently, (February 2020), Oil Now cited an S&P Report which posited: “Analysts foresee many more discoveries and further increases to the 8 billion BoE”. Further, Rystad Energy in January 2020, commented favourably that, “in 2019 Guyana overtook Russia as the largest producer of conventional discovered resources.” This achievement together with its 2018 performance, has helped ExxonMobil to earn the title “Explorer of the Year” for the second year in succession.

Conclusion

Next week I’ll start by adding to this evidence of world class potential, before providing my estimation and the rationale on which it rests. The question I pose is: does world class potential trump a baptism of fire and brimstone?