LONDON/GENEVA (Reuters) – Pine trees are bursting into flames. Boggy peatlands are tinderbox dry. And towns in northern Russia are sweltering under conditions more typical of the tropics.

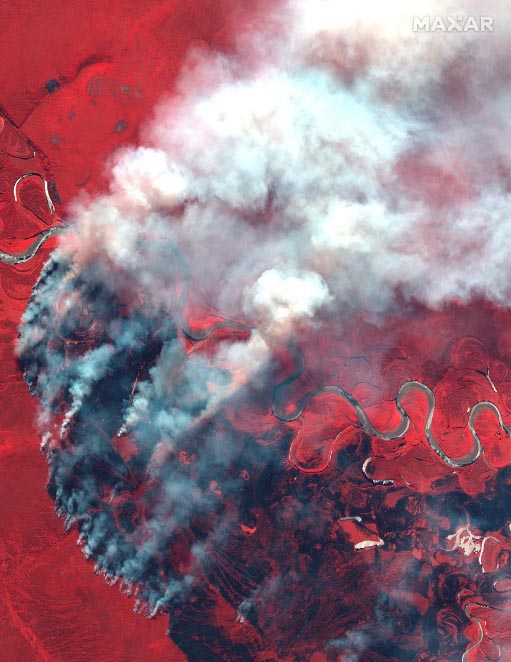

Reports of record-breaking Arctic heat – registered at more than 100 Fahrenheit (38 Celsius) in the Siberian town of Verkhoyansk on June 20 – are still being verified by the World Meteorological Organization. But even without that confirmation, experts at the global weather agency are worried by satellite images showing that much of the Russian Arctic is in the red.

That extreme heat is fanning the unusual extent of wildfires across the remote, boreal forest and tundra that blankets northern Russia. Those blazes have in turn ignited normally waterlogged peatlands.

Scientists fear the blazes are early signs of drier conditions to come, with more frequent wildfires releasing stores of carbon from peatland and forests that will increase the amount of planet-warming greenhouse gases in the air.

“This is what this heat wave is doing: It makes much more fuel available to burn, not just vegetation, but the soil as well,” said Thomas Smith, an environmental geographer at the London School of Economics. “It’s one of many vicious circles that we see in the Arctic that exacerbate climate change.”

Satellite records for the region starting in 2003 suggest there has been a dramatic jump in emissions from Arctic fires during just the last two summers, with the combined emissions released in June 2019 and June 2020 greater than during all of the June months in 2003-2018 put together, Smith said.

Atmospheric records dating back more than a century show Arctic air temperatures also reaching new highs in recent years. That leads Smith to believe the scale of the fires could be unprecedented as well.

“What we’re seeing happening right now is the consequence of the past” industrial emissions, Smith says. “What will happen in 40 years’ time is already locked in. We can’t do anything about that. That’s why we should be concerned; it can only get worse.”

Although peatland covers only 3% of the Earth’s land surface, those deposits contain twice as much carbon as all the world’s forests together.

A NEW NORMAL

Scientists have known climate change is causing the Arctic to warm twice as quickly as the rest of the world, and the Siberian heat wave, which began in May, is typical of that trend.

“It becomes like an oven,” said Walt Meier, a senior research scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center at the University of Colorado who specialises in sea ice. “You are doing that on top of the longer-term warming trend, so you are getting the oven nicely baking a pie to scorching it.”

“What used to be extreme is becoming normal. Warmer temperatures are now relatively frequent,” Meier said.

And as temperatures warm, and polar snow and ice melt, more Arctic area is left darker and absorbs heat faster, which contributes to more warming. The Arctic sea ice has lost 70% of its summer volume since the 1970s, with the area also shrinking to the point that last year saw one of the lowest ice covers on record.

“WARNING CRY”

The peat fires make the need to cut man-made emissions all the more urgent, say scientists, who warn that wider changes in the Arctic could trigger bigger impacts on the global climate system.

“It’s a huge warning cry that’s going off, but it’s not the only systemic problem that’s happening in the Arctic related to climate change,” said Gail Whiteman, incoming professor of sustainability at Britain’s University of Exeter and founder of the Arctic Basecamp group of scientists advocating for rapid climate action.

Whiteman and other researchers are also worried about the rising heat thawing Arctic permafrost here faster than expected, which is liable to produce far larger quantities of carbon dioxide and methane than are being released by the fires.

Guido Grosse, head of the Permafrost Research Unit at the Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research in Germany, said the fires were stripping away peat and vegetation that normally would form a protective blanket over the permafrost.

“If you take this away the heat from the summer penetrates directly into the ground and warms the permafrost, and it starts thawing,” he said. “You see this effect usually a few years after the fires.”

The warming temperatures also appear to be making the Arctic wildfire season longer, said Jessica McCarty, an assistant professor of geography at Miami University in Ohio. Typically, the Arctic fire season runs from July to August, plus or minus a couple of weeks. This year, fires were detected in May.

And “as the peat burns … its neighbor next door gets warmer, and their neighbors get warmer,” McCarty said. “We’re burning up these ancient pools of carbon.”